'Gunners - British Artillery in WWII'

This weeks excerpt comes from a recent comprehensive study of British Artillery

Stig H. Moberg was an officer in the Swedish Artillery Reserve for many years before writing his comprehensive study of British Artillery. Gunners - British Artillery in WWII was first published in 2013 with a revised English edition appearing in 2016. This is an invaluable work for anyone wanting to understand how Artillery functioned during the war.

He begins with setting the context ‘Historical background - War and Re-Armament’ before a long section on ‘Gunnery Methods, Procedures Tactics, Staff Work’ which explains, in a very accessible manner for the layman, the many intricacies that lie behind the art and science of Artillery.

Then almost half the volume is concerned with Battle Histories - covering El Alamein, Normandy and Arnhem among others.

The following excerpt illustrates the author’s approach, integrating personal accounts with his own overview of the battle:

21.40 hours on 23 October 1942

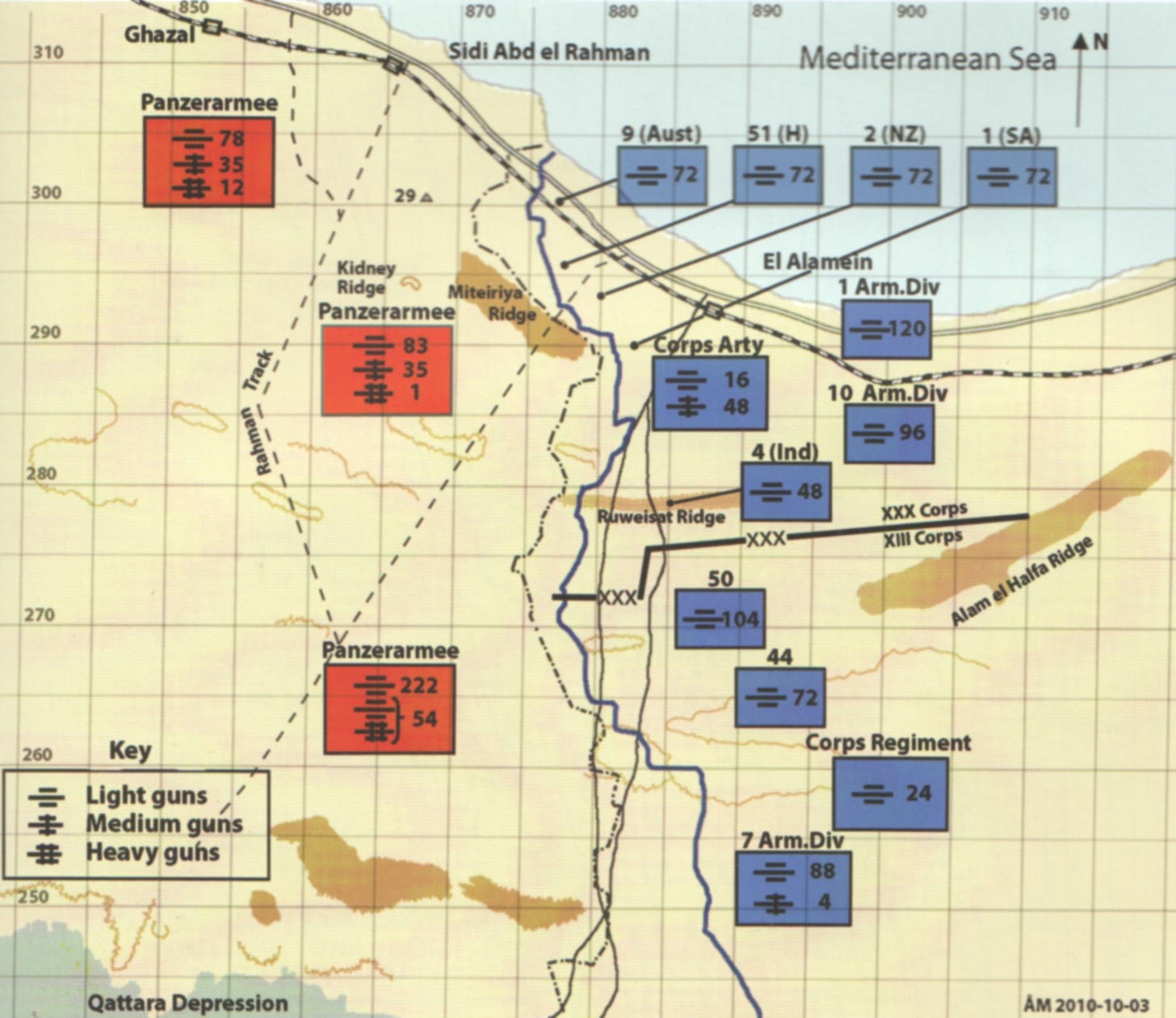

At this time the thunder of the guns broke the silence when all the artillery in the northern sector opened fire, see Map 19-4 [above] and Map 19-6. With Montgomery’s words: ‘We are now ready’. One and a half month of preparations after the second battle at El Alamein was over, and the troops and equipment were in the best order and readiness. The extensive exercises and rehearsals with live ammunition had raised self-confidence.

The large deception programme, Operation Bertram, seemed to have worked well. Advancing lanes were in good order; the battle positions were prepared during many nights and were well camouflaged and had now been occupied by their units, ammunition stores were complete etc. The Game could commence. And the attack surprised the enemy.

At the time given above, artillery opened fire from the Mediterranean coast to the Qattara Depression in the South. The sky was illuminated by muzzle flashes and the noise was deafening, everything almost unreal to those present (Fig. 19-5). Never had anyone experienced such a violent artillery bombardment during the first years of the war. After three years, the British Army had gained this capability.

The commanding officer of 11 (HAC) Field Regiment RHA who moved forward with his new ‘Priests’ at the end of one armoured battalion column of the 1st Armoured Division gave later his account of what he experienced this night:

Waiting in the ‘deception’ leaguer under no movement orders was hot and boring, but by the early evening of 23rd October we were all set. Peter Thompson Glover (G. Troop) and Tom Butler Stoney (H. Troop) and myself went over to a brief orders at the 9th Lancers and had a quick drink - back to the Battery with orders to move into our positions in the 9th Lancers column at 19.30 hours.

Last minute personal preparations, a curious and apprehensive quiet pervaded, still no movement from our ‘hides’ was permitted for even now a Boche recce plane might put in an appearance - waiting as the sun went down in its usual glorious technicolour came that old hollow feeling in the stomach!

Engines were warmed up and as the full moon rose in the cloudless sky, a great orange red ball until it cleared the lower atmosphere, when it and the desert turned silver, the air was filled with the deep throb of the hundreds of diesel engines.The long lines of tanks and guns moved forward towards the start line, an ominous black frieze against the light of the desert. Then above the engine noise came the familiar drone of Boche plane, followed by the whistle and crump as a single bomb was dropped - a suitable reminder this was not a practice run!

As the column advanced we passed battery after battery - guns dug in, piles of ammunition - the gunners resting waiting for Zero hour, many gave us cheery greetings - as we reached the start point it was Zero hour - the moon now high, visibility surprisingly good - the distant blackness erupted in a vast curtain of fire from right to left as far as the eye could see, a thunderous explosion of noise as some 800 guns along the front opened up - the fire plan had started. The middle distance was filled with flickering flashing of the guns, the horizon aglow with small bursts, the glare of searchlights reaching up in cross lines forming ‘trig’ points for directional aids, Bofors firing on fixed lines streams of tracer marking boundary lines - Brocks famous fireworks were not in it!

A halt to top up diesel and petrol, and take off gun covers - so far not a single shell had come from the Boche - the barrage had lifted and it was now bitterly cold as the column started forward again - as a 9th Lancers said ‘2.0 am is not a time to feel particularly brave!’

As we moved on we could hear the crackle of small arms as the infantry and R.E. Minefield clearing taskforce fought their way through the Boche lines. We passed through our own minefield directed by the Military Police until across the ‘neutral’ ground we reached the first Boche minefield — the entrance marked with shaded red and green lights and white tapes. Our eyes tired and strained by the dust despite goggles, made out dim shapes of smashed gun pits, tangled wire and minefield Crossbone signs, then a few bedraggled and dazed prisoners - almost no shelling, our counterbattery work had been good!

A detachment, which had experienced hectic work, was the Counter-Battery [C.B.] Officer and his staff This is how he experienced the start of the offensive:

The whole C.B. Staff take up position on high ground in front of the C.B. Office to watch the labours of the past week put into effect.There was a tenseness and expectancy over the desert but almost instantaneously this was replaced by a shattering roar as the horizon was lit from end to end by the flashes of 372 Field and 48 medium guns all firing C.B.

In the sector where the main attack was launched some 400 guns now opened fire against enemy batteries located earlier. The fire was concen trated in time over these in such a way that a superiority of 20:1 was accomplished if possible, but it should never be less than 10:1.

In the southern sector, the counter-battery fire was commenced ten minutes earlier, i.e. at 10.30 hours, here too by several hundred guns. No medium guns were available there apart from the four French guns.

Ranging was, as mentioned, not to take place for security reasons. It was still important to do as much as possible to ensure accuracy of the fire. Correct fixation of gun positions and targets was of course important and the required survey must have been performed properly.

Availability of good weather data was equally important. This was accomplished by having a medium regiment to fire airbursts one and a half hour before the main opening of fire; the bursts being measured by the surveyors from their observation posts. This gave sufficiently good data to remain valid for a few hours ahead, it was hoped. Met telegrams were then distributed every second hour, sometimes in shorter intervals.

This was very important. Wind conditions on the actual day were such that the fire impact would deviate from the correct position by some 700 yards had not the correct ‘Correction of the Moment’ been applied.

All fire plans across the two Corps areas were, as we have seen, carefully coordinated in terms of fire intensity and timings. This was new in the Desert War and aimed of course at accomplishing best possible concentration of firepower as Montgomery had requested. Work at command posts was very demanding.

This excerpt from Gunners - British Artillery in WWII appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright for text and image remains with the author.

See also Britain's Desert War in Egypt & Libya 1940-1942 for a more general account of the El Alamein battle.