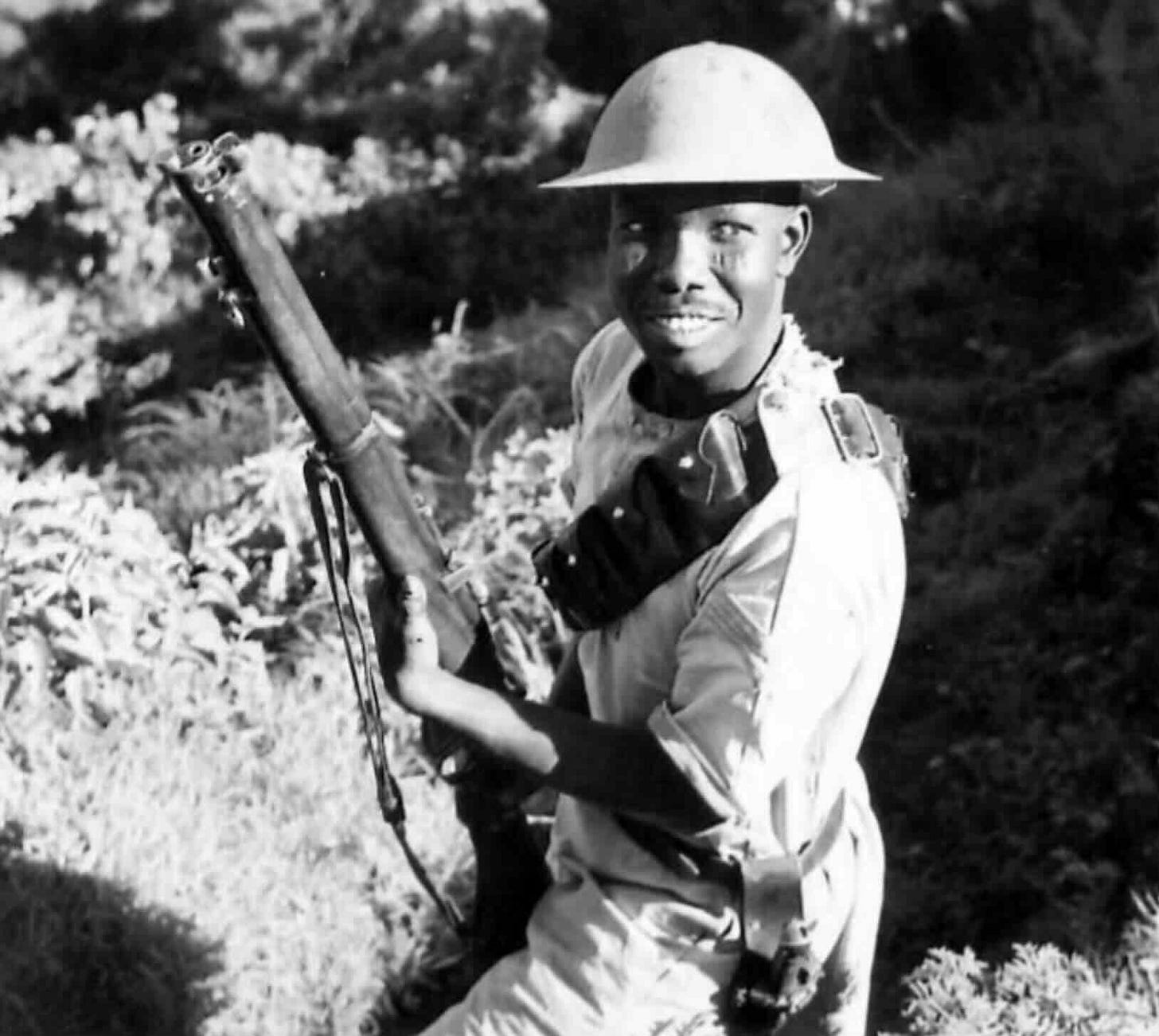

Gideon Force prepares for battle

27th December 1940: An irregular force of Abyssinians loyal to Emperor Haile Selassie forms up under a small group of British Officers, alongside Sudanese troops

The British were successfully counterattacking the Italians in North Africa, but also had ambitions to take the fight to East Africa. Mussolini had subjugated the independent empire of Abyssinia (now Eritrea) in 1936 in a brutal war that pitched modern weapons and poison gas against the native forces. The exiled Emperor Haile Selassie, regarded as a living god by many of his countrymen, returned, now in alliance with Britain.

‘a sword of rare metal has been cast out of a dozen Englishmen and a few hundred Africans’.

In addition to two British Indian Divisions, the assault on the occupying Italian force would be supported by irregular Abyssinians under British officers. They were led by an eccentric British officer, Orde Wingate, who would later gain fame for leading the Chindits in Burma, another unconventional force. The story is told in Bare Feet and Bandoliers: Wingate, Sandford, the Patriots and the Liberation of Ethiopia:

Wingate called his small force ‘Gideon Force’. This name is illustrative of Wingate’s character and biblical knowledge. Gideon, in Judges 7:7, ‘chose the 300 men that lapped’ , surrounded the Midianites so that they panicked, and ‘the Lord delivered them into his hand’ . Wingate surrounded the Italian garrison at Burye and induced their commander, Colonel Natale, to believe that he was surrounded by a large force, so that he panicked and retreated. Wingate knew exactly what he wanted to do and chose a biblical reference to fit it.

Wingate arrived at Roseires on 24 December to find half his force assembled there, the Frontier Battalion, the Ethiopian mortar platoon, and No 1 Operational Centre. These units must be briefly described.

The Frontier Battalion was a formidable unit of five patrol companies, each recruited from one of the five SDF corps areas, and each about 250 strong so the total strength was about 1250, with 14 British officers. The men were mainly Muslim Arab Sudanese, with Nubas in No 5 patrol company and some Nubas in No 1, the majority new recruits with some re-enlisted soldiers, under experienced regular NCOs and warrant officers, all soldiers of high quality with a long tradition of service.

Of the British officers, four were regulars, the others from the Political Service, the Plantation Syndicate1 or commercial companies, all Arabic-speaking with long experience of the Sudan and able to communicate (and joke) directly with the men. Each company also had experienced Sudanese officers. This was a highly efficient disciplined unit, which nearly always performed with distinction, equipped with modern infantry weapons and trained by Boustead to shoot straight and conserve ammunition. Dick Luyt, a sergeant in the 2nd Ethiopian Battalion, described the Sudanese as a rock in the whole campaign’ , and to Wingate ‘the sight of an emma [turban] on a hillside was worth a hundred men’ .

In the words of W. E. D. Allen, later their animal transport officer, ‘a sword of rare metal has been cast out of a dozen Englishmen and a few hundred Africans’.

The Ethiopian mortar platoon consisted of one officer and 50 men, all Ethiopians, who had been recruited at Gedaref by Nott from the Patriots of Shalaka Mesfin and trained by Sergeant West of the 2nd West Yorks. They were equipped with four three-inch mortars made in the railway workshops in Khartoum, which were carried on mules with the ammunition. This unit arrived with Nott and rear HQ Mission 101, also with Mesfin, who wanted to go in with them but was refused permission by Haile Selassie. The mortar platoon were Wingate’s only artillery and performed well throughout the campaign, including the Gondar operations, suffering 50 per cent casualties.

No 1 Operational Centre was the first to arrive of ten such centres recruited from volunteers in Middle East Command. It consisted of one officer and four sergeants from 2nd/lst Field Regiment of the 6th Australian Division, then stationed in Palestine, and 240 Ethiopian askari recruited from the refugees in Khartoum. Its history was different from that of the other centres in that the officer, Lieutenant Alan Brown, volunteered for sabotage work in Ethiopia after talking to an Ethiopian Coptic priest in Jerusalem before the Eden conference, persuaded the four sergeants to go with him, and they were undergoing commando training in Egypt when the call for volunteers went out.

Wingate’s other infantry battalion, the 2nd Ethiopians, did not arrive at Roseires until 5 and 6 January but will be introduced here. Recruited from the Ethiopian refugees at Taveta, the unit consisted of six British officers, four sergeants and 600 Ethiopians,including 24 officers. None of the British officers were regulars, not even the commanding officer, Major Ted Boyle; Michael Tutton, a DO from Tanganyika, was the only native Englishman, the others were ‘colonials’ .

All the Ethiopians were former soldiers of Haile Selassie’s army, the officers selected because of the rank they held under the Emperor, the other ranks for their physical fitness. The battalion had had four months’ basic training, three in Kenya and one at Soba camp near Khartoum. They were equipped with 1870 French Labella single-shot rifles, and a few Lewis and Vickers machine guns and Boyes anti-tank rifles, which they had picked up in Uganda during the month-long journey by rail and river steamer from Mariakani to Khartoum.

This was very much a scratch unit, the men natural soldiers but with little formal training, the officers immensely keen but inexperienced, and there was a weakness in command. Communication between officers and men was in basic Swahili, which the men had picked up in Taveta camp. The unit’s performance in the campaign was patchy, fighting with great gallantry at the Charaka river action on 6 March, after that suffering some lapses but finishing strongly at Gondar.

There was nothing wrong with the spirit of the men. Dick Luyt recalls that at Gotani camp in Kenya they forswore drink and women until the Emperor was restored to his throne, a pledge they did not always honour. After retreat each evening they held their own ceremony, praying for the success of the campaign and the freedom of their country. Luyt found these ceremonies moving.

To get this force to Belaiya and thence into Gojjam required an enormous number of baggage animals, and these could only be camels hired from the Sudanese since mules could not be obtained in sufficient numbers from the Patriots. The camels were obtained and got to the assembly area through the help of district commissioners and veterinary officers and pressure from Wingate on the Sudan government - 25,000 according to Wingate, 18,000 according to Allen, with 5000 camel drivers. Particular credit must go to two veterinary officers, John Jack and Ian Gillespie, who examined the animals and passed them fit for the journey, the same two officers who had helped Bentinck with the crossing of the Atbara river. Very few of the camels survived the journey but they were a necessary sacrifice.

© David Shirref 1995, 2009, ‘Bare Feet and Bandoliers: Wingate, Sandford, the Patriots and the Liberation of Ethiopia’. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd. NB Not all of the above images are from this volume.

What is great about these World War II Today posts? You read a little about people like Haile Selassie of Ethiopia during World War II as a youngster. These posts bring it to life, great reads! Thank you.