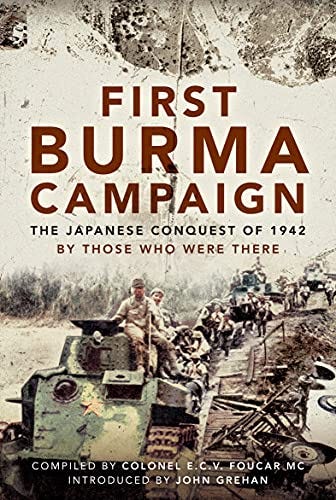

After the British defeat in Burma in 1942 Colonel E.C.V. Foucar was given the job of writing an account of the campaign. Despite the difficulties of piecing together the story from surviving witnesses he succeeded in producing a comprehensive account that does justice to the men who fought in Burma - many of whom died here. It is a dramatic tale that makes as much sense as possible of what was often a very confusing situation.

This official British military history first became available in published form in 2020 - and is essential reading for anyone interested in the campaign, especially those who had relatives here. Every effort is made to name the different units that were involved in each individual action.

The following excerpt relates to the debacle at the Sittang Bridge - described by one historian as ‘the defining moment in the decline and fall of the British Empire’. In the early hours of the 23rd February 1942 the decision was made to blow up the bridge. This left the greater part of the 17th Division on the wrong side of a mile wide river facing constant attack from superior Japanese forces.

It is of note that many individual officers are named in this account - but not the commander of the 17th Division.

The bridge having been destroyed it was necessary to consider the situation.

Brigadier Jones decided to maintain his positions round Mokpalin during the day of February 23rd. Casualties were to be evacuated by raft, and troops thinned out. Complete withdrawal would be effected before first light on February 24th.

All men who could be spared would be employed in building rafts. No men were to cross the river until ordered to do so. The plan was communicated to Unit Commanders at 0930 hours. A V.C.O. of the Jats volunteered to swim the river carrying details of this plan to Divisional Headquarters. However, a small boat was discovered and the V.C.O. crossed the river in this, safely delivering his message.

Since first light heavy fighting had been in progress. Shortly after 0730 hours the position of the 3rd Gurkha Rifles on the perimeter was attacked with determination. The Japanese were thrown back with severe loss, the Battalion mortars firing with great accuracy. Of this repulse of the enemy the Unit War Diary says: "This was the hardest single blow the Battalion gave the Japanese at the Sittang."

A small single engine Japanese aircraft audaciously flying at a height of only sixty feet or so, carried out a reconnaissance of Mokpalin. Immediately afterwards, at 1000 hours, infantry guns and mortars shelled our main artillery positions near the Railway Station.

‘Horses and mules stampeded; ammunition exploded; some men made their way to the river and began to swim across. No efforts by officers could restrain them. Fighting flared up on the east and south. With the exception of the 4th Battalion Burma Rifles, which broke, all troops in position on the perimeter held their ground. The attempts of the Japanese infantry to advance were repulsed. After three quarters of an hour the attacks died away.’

Horses and mules stampeded; ammunition exploded; some men made their way to the river and began to swim across. No efforts by officers could restrain them. Fighting flared up on the east and south. With the exception of the 4th Battalion Burma Rifles, which broke, all troops in position on the perimeter held their ground. The attempts of the Japanese infantry to advance were repulsed. After three quarters of an hour the attacks died away.

On repeating its reconnaissance flight, the small Japanese aircraft, for the appearance of which our troops were prepared, was shot down. Its fall was greeted by loud cheers.

As many men as could be spared from the defence were set to work building rafts from the bamboos and timbers of huts and buildings, and in collecting petrol tins, water bottles, and other buoyant articles. A matter that caused grave anxiety to all commanders was the evacuation of the wounded which began at once. Many of the slightly wounded swam the river, more serious cases were taken across on rafts. But in spite of every effort of doctors and others it is feared that the vast majority had to be left on the battlefield.

At 1115 hours a formation of about twenty-seven Japanese bombing aircraft made an attack on our positions and on the massed transport along the main road. The bombing caused considerable damage. More gun ammunition and vehicles were set alight, houses and the surrounding jungle began to bum, and there were a number of casualties. Enemy mortar fire increased. Sniping and small arms fire continued against our troops south of the Railway Station.

Brigadier Jones visited units and was satisfied that some troops were now in no condition to hold out much longer. To attempt to maintain our positions until nightfall might lead to disintegration. Under the circumstance's orders for a general withdrawal at 1400 hours were issued. These orders did not reach some posts with which it was impossible to get into touch.

Defensive positions were withdrawn towards the river bank, but fighting still continued from isolated posts south of the Railway Station and east of the main road. The Japanese did not follow up the withdrawal and it is probable that after the severe casualties they had sustained they were in no mood to do so.

The remains of Mokpalin village and other buildings were fired. So, too, were vehicles. These conflagrations and the burning ammunition dumps made a protective barrier for our retiring troops.

Guns were dismantled, the breach mechanisms and sights being thrown into wells or the river. Machine-guns and mortars were similarly treated. Many men cast their rifles into the Sittang.

The scene on the river bank which was protected by a cliff has been described by a senior officer.

"Here was chaos and confusion; hundreds of men throwing down their arms, equipment and clothing and taking to the water It is only fair to emphasise the conditions under which these men had been fighting.

17 Division had now been fighting almost day and night for five weeks continuously in most difficult country against a superior and far better trained enemy. They were exhausted after their non-stop efforts since the recent battle of Bilin river, and now they were attacked by two Japanese Divisions, and their only line of withdrawal, the Sittang bridge, had been destroyed As we crossed, the river was a mass of bobbing heads.

We were attacked from the air and sniped at from the opposite bank. Although it was a disastrous situation there were many stout hearts and parties shouted to each other egging on others to swim faster with jokes about the boat race! Some took their arms with them on rafts."

Certain units maintained their cohesion to the last until men received the order to enter the water and to make their way across the river. Sections endeavoured to keep together, the men helping one another. Many men in their attempt to swim the river were drowned; others who could not face the ordeal walked back into the jungle and, if not captured, contrived to cross the Sittang further north.

There were magnificent acts of devotion and bravery. Swimmers assisted non-swimmers, and men swam across the river two or three times to bring in the wounded. Each journey entailed the passage of the swift flowing stream well-nigh a mile wide.

Our guns on the west bank of the Sittang rendered what support was possible and succeeded in keeping down enemy machine-gun fire.

This excerpt from First Burma Campaign: The Japanese Conquest of 1942 appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.