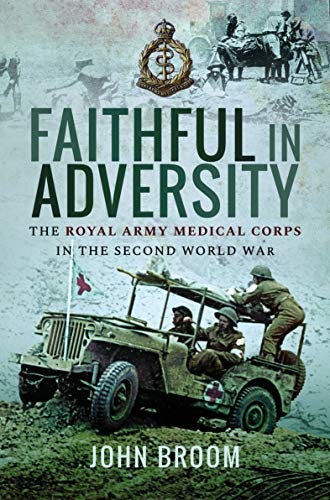

'Faithful in Adversity'

A history of the RAMC told through personal stories

Faithful in Adversity: The Royal Army Medical Corps in the Second World War is a wide ranging survey of the many different challenges faced when treating the wounded in World War II. Each theatre of the war is considered using numerous personal accounts from private diaries, letters and official accounts. An excellent single volume overview.

The following passage considers the role of the RAMC in NorthAfrica, illustrative of the approach taken by the author, considering the particular medical problems faced and the typical experiences of those under their care:

Performing medical procedures was far from straightforward in the North African desert. The all-pervasive sand aggravated every skin disease, causing desert sores, and painful and demoralising skin ulcers. These were difficult to prevent without ample soap and hot water, and harder to cure, keeping soldiers off duty for many weeks.

The prevalence of tank warfare produced many cases of severe burns. The removal of badly burned or wounded patients from a ‘brewed-up’ tank was a hazardous exercise, and the vulnerability of such burns to the desert sand could seriously exacerbate any injuries. Raw skin and flesh had to be dressed without delay, and tannic acid was used for this early in the war.

This proved ineffective, so a better alternative was quickly found in sheets of gauze impregnated with surgical jelly to which sulphanilamide had been added. Loose gloves made of waterproofed silk were sealed to the wrist, excluding infection and relieving pain during transport.

‘Though badly stricken himself and suffering intense pain from severe wounds in the pelvis and shoulder, he continued for about eight hours to give directions to his stretcher-bearers on how to deal with the wounds as they were brought to the RAP.’

One of the earlier acts of heroism by an army medic was performed on 12 December 1940 during the Battle of Sidi Barrani. Lieutenant J.M. Muir was the medical officer attached to the 1st Battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Muir was hit at about 7.00 am by a shell splinter but despite his wounds he insisted on being propped up in a sitting position beside his vehicle and refused an injection of morphine in order that his senses might remain clear.

Though badly stricken himself and suffering intense pain from severe wounds in the pelvis and shoulder, he continued for about eight hours to give directions to his stretcher-bearers on how to deal with the wounds as they were brought to the RAP [Regimental Aid Post]. He remained at his post until the last wounded man had been evacuated and only then about eight hours after being wounded, did he consent to be placed in the ambulance himself. For this action, Muir was awarded the DSO.

The treatment received by Fusilier W. Close demonstrated the various layers of medical intervention a wounded man could receive, as well as the informal support given by army chaplains and camp followers to the men of the RAMC. Close had joined the army as a regular solider in 1933. He had served with the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers under General Wavell when the Italians were pushed back to Benghazi and during the subsequent British retreat to Tobruk.

While manning his machine gun one evening in August 1941, a German mortar shell landed near him. Close was thrown forward but his life was saved by the corrugated iron roof and four layers of sandbags. He was temporarily blinded and blood was running into his eyes and onto his chest. Shrapnel had pierced his face.

Once the German shelling had finished, medical evacuation procedures and treatment were implemented. Firstly, he was guided, along with two other casualties, down a slit trench. They reached a gun pit filled with ammunition and spare parts.

The platoon sergeant had applied a wooden splint to one of the men who had broken his arm but he was unable to help Close, who could feel the shrapnel sticking into his face. His comrades convinced him not to touch it and tried to distract him with jokes.

Next, Close was carried 600 yards by four stretcher-bearers to a South African dressing station nicknamed ‘The Fig Tree’. An Australian padre was present, and he offered to cable home to Close’s family to tell them he was safe. The padre also gave Close ten cigarettes and sent for the fusilier’s mate, to whom he wanted to hand over his personal property.

Medical staff strapped his arms to his sides to stop him scratching his face and administered some morphine to dull the throbbing pain. He was taken on a jolting road journey by ambulance to another dressing station twenty minutes away, where he was given a cup of tea with no milk or sugar, and another shot of morphine. The staff asked if he was all right, to which Close replied, with dark humour, ‘It’s the rich food’s my trouble.’

Close was then evacuated further back to Tobruk Hospital where he was operated on immediately. The shrapnel was removed from his face and his eyes were cleaned. When he awoke the next day his head was covered with bandages, and he was still blind. Close firmly believed that he had lost his sight for good.

The following midnight, Close was evacuated from Tobruk by barge to a destroyer, which sailed to Alexandria, where his eyes were operated on. He recuperated at that hospital for a month and was then taken to a dark room and his bandages were removed.

There was a revolving wheel that staff used to try to coax Close’s eyes back into use. They washed his eyes four times a day and performed different tests on them. Gradually the film of blindness was lifted from his eyes until he could eventually see again. During the rest of his recuperation, his adjutant’s mother took him and two other wounded fusiliers out.

A medical report was conducted that classified Close as a ‘B’, which meant he would be given a job at the base depot and not be sent back out into the desert. This upset Close, as he wanted to be back with his old company, so he persuaded the medical officer to upgrade him to ‘A1 ’ He sailed back to Tobruk just in time for its relief on 27 November 1941.

This excerpt from Faithful in Adversity: The Royal Army Medical Corps in the Second World War appears by kind permission of the publisher, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, copyright remains with author. The images above do not appear in this book.