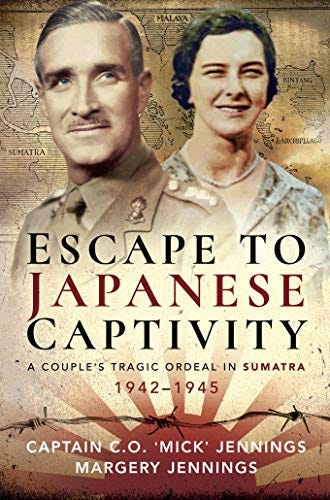

Captain Mick Jennings (1899-1964) had served in the Royal Engineers from 1917-1919 before a career as an architect in the Colonial Service, eventually becoming the municipal architect of Kuala Lumpur in 1935. He found himself rejoining the Royal Engineers when the Japanese invaded Malaya in 1941.

His account of his escape from Singapore and an attempted escape from Sumatra (with one companion, sailing the open ocean in a dingy for 127 days) was published as ‘An Ocean without Shores’ in 1950. That volume has now been republished by Pen & Sword - alongside an expanded account of his time in captivity - as well as his wife's account of her captivity in Sumatra, making three different books in one.

‘An Ocean without Shores’ was an ‘adventure story not a war story’. It began with his escape from Singapore in February 1942. Many men attempted to escape from Singapore. Few of them wrote about their experiences - the following excerpt is a rare account from one of them:

We waited and waited, not a single word said between the three of us. Cigarette ends littered the floor at my feet. It was obvious something momentous was afoot and the OC knew much more than he cared to say. It was 5.25 pm when the phone rang again. The information transformed Colonel Meade into an old man.

He put the receiver down and, turning to me heavily, said, ‘Jennings, please get the men in a circle. I want to speak to them.’

Clambering up the dugout steps, I gathered the troops and a few minutes later he stood with his men around him and said:

‘Gentlemen, today at 4.30 pm the British Commander-in-Chief surrendered unconditionally to the Japanese Commander-in-Chief. You are now at liberty to try to escape or to stay, as you desire; but if you go I am to advise that you go in uniform otherwise, if captured, you may be shot as spies. That is all.’

‘There are moments in a person’s life which can never be forgotten. Moments of beauty, love or achievement, hate or hopelessness, and moments of breathtaking amazement and disbelief.’

There are moments in a person’s life which can never be forgotten. Moments of beauty, love or achievement, hate or hopelessness, and moments of breathtaking amazement and disbelief. Although it had been clear for the past week there could be no other ending than this, the shock of being told the end had come held us silent and still, staring at the man we had come to love and respect, waiting until he should break the spell which had descended.

A shell bursting closer than usual brought us back to reality and reminded us that if we wanted to make a bid for freedom even minutes were important. I went up to Colonel Meade, saluted, shook hands and said goodbye. I had made up my mind to try to escape. How, I knew not but I hoped the opportunity would present itself.

The great thing was not to be captured, and an intense desire for freedom seized me. Could it be done? Was it too late? My wife had left a few days earlier on the Mata Hari and I trusted she was well on her way.

Everyone seemed to be of the same mind and rushed to cars and lorries. Only the sea could offer the chance of escape and going up to my car I threw out the bag which contained all the personal belongings that remained to me. It was no good being hampered with a heavy suitcase when attempting to escape. In convoy with other cars, some twenty-seven of us retraced our way down Tanglin Hill.

‘It was evident they had not yet been told of the capitulation. It was a heartbreaking sight which made the lump already in my throat much larger. It seemed shameful to be creeping away, but we had been given a chance of escaping and were naturally trying to make the best of the opportunity.’

On either side of the road were our silent guns and standing by them were the bewildered gunners who had fought so splendidly, idly watching our procession of cars. It was evident they had not yet been told of the capitulation. It was a heartbreaking sight which made the lump already in my throat much larger. It seemed shameful to be creeping away, but we had been given a chance of escaping and were naturally trying to make the best of the opportunity.

What chaos the wharf presented! Frustrated troops could be observed hurrying from one boat to another in the hope of finding something, anything, in which to get away.

Two RAF launches appeared to be the focal point of hope, judging from the crowd. They were afloat and apparently undamaged so towards them we made haste with more speed than dignity. Here and there military police were vainly trying to stop men from what appeared to be wholesale desertion.

We boarded the already overcrowded RAF launches and inspected the engines. The injector plugs were missing so it was no use wasting any further time on them. Coming on deck I peered over the side and noticed a small dinghy with seven men in it. Here was the chance I was looking for.

Handing my Tommy gun and haversack containing food and cigarettes to an officer, I told him I would bring the boat back, and leapt over the side of the launch into the boat just as the occupants were attempting to push off. I scrambled forward and to someone’s instructions we took off our tin hats and paddled for all we were worth as the light was rapidly failing.

Some 500 yards seaward lay the breakwater which divided the inner roads from the open sea. It was deep twilight by the time we reached it. We had got off the island, but only just.

Moving eastwards along the breakwater, we came to a point opposite the useless RAF launches, when a lone soldier appeared and asked if we knew where fresh water could be obtained. One of our party gave him a drink, after which he informed us that he belonged to another party of troops a short distance away.

A minute or two later we came upon seventeen other men who had obtained another small dinghy, on the seaward side of the breakwater. We banded together, making a party of twenty-five in all.

In this group of men I met Captain Crawley, RA, who was trying to get some sort of organization into this escaping business, and the dinghy made several trips to one of the tongkangs [junks]. On one tongkang we came upon a small certificate fastened to the bulkhead, which informed us that we were on the Hiap Hin of 135 tons registered berth, a sound, solid and seaworthy craft.

The water tanks were full and in the hold were six bags of rice. We crept about in the darkness of our unfamiliar new home but found nothing else that was edible. We did, however, find some clothes which had belonged to the previous crew.

The knowledge that the vessel was empty of cargo and therefore riding high in the water gladdened our hearts for we knew that whatever course we laid, we had to sail through our own minefield.

This excerpt from Escape to Japanese Captivity: A Couple's Tragic Ordeal in Sumatra, 1942–1945 appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.