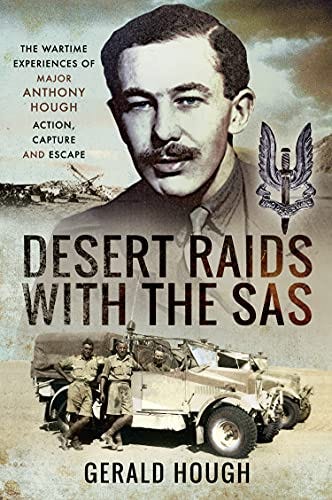

Desert Raids with the SAS

Memories of Action, Capture and Escape

First published in 2021 Desert Raids with the SAS: Memories of Action, Capture and Escape is the memoir of Major Anthony Hough. In 1940 he volunteered for Ski training and was on the brink of being sent as part of a British force to Finland. By 1941 he was in the Libyan desert with 9th Battalion the Rifle Brigade - which suffered heavy casualties in early 1941 when Rommel had success with his first attacks on British lines. By September 1941 the Battalion had been rebuilt and Hough was again on the front line in the desert - this time making probing patrols as the British prepared for another offensive

The following passage describes life in the desert September-October 1941. This proved to be very valuable experience for when he later joined the SAS, who were to become masters of deep raids into the desert. A highly readable account which will be of particular appeal to those with an interest in the early days of the SAS. But Hough had a very active range of experiences right across the desert for 18 months before ehe made that move, and his war experiences were far from typical even after his capture whilst on an SAS raid.

We remained here until late September when we were again placed under overall command of the 201st Guards Brigade and sent forward to take over from the 2nd battalion, which at the time was just east of Mersa Matruh at a place called Gerawla.

Here we undertook extensive patrols right into the heart of the enemy and sometimes through and behind them. The patrols were exhausting as the officers were required to go out three nights in four and we had to get close to the enemy in order to collect vital data on minefields and dispositions.

A patrol required us to drive some eight to ten miles in the dark across the desert on a compass bearing and speedometer reading and then a two to three mile march on a compass bearing checked by pacing. Once close enough to the enemy we would gather data about their dispositions and lay some mines.

Occasionally we would come dangerously close to enemy patrols or sentry positions but usually were able to silently withdraw in the darkness. Patrols having direct contact and a firefight would invariably get into difficulties and some or all would not return. Once we had as much information as we could get, we would retrace our steps on a bearing to the trucks and drive back in the dark to our lines. We had to get back before daybreak otherwise would be exposed to air attack.

The information we collected was by all accounts very well received by HQ as it gave details of infantry dispositions, minefields and positioning of main armaments. There were times we were so close to the enemy we would be crawling between two defensive posts.

All the time we were faced with dealing with the dreaded mine, and so many of them, sown by both our side and the Axis. The Germans had a really nasty one called the S-mine, or shrapnel mine. When triggered it would jump out of the ground to about four and a half feet then drop a foot before exploding, sending ball bearings at very high velocity in all directions. Anyone within fifty yards could be injured.

They were easy enough to disable once discovered but discovery wasn’t always easy. The Italians invented their own nasty one which was encased in a wooden box so that our detectors wouldn’t pick up the metal signal. We lost a fair number of men to these devices, either with their losing their feet or legs or being killed outright. There were thousands of mines used as defensive measures to force attacking forces into a narrow channel and they were a constant dread.

We had no significant major engagement with the enemy during this time, and those of us who had survived the intense fighting in April found this comparatively gentle rebreaking-in was a great help to morale.

...

Life in the desert is a healthy one even though we lived mostly on bully beef and biscuit. Water was scarce most of the time and we had to be clever with its use. We would cut a used petrol can in half and punch small holes in its base, over which we would lay a cloth. On this we would lay a few inches of sand. We would share water for washing and rotate who went first. After a wash and a shave, the water would be filtered through the can, coming out crystal clear and ready for the next person. We could keep water rotating this way for several days before it became foul. Rather than discard it, it was then used to top up the vehicle radiators.

The desert sand is hard to sleep on, and other than in the summer months, when the heat can become unbearable, it can be very cold at night, although pleasant during the day. There was more often than not a cooling breeze which would fall away around midday making it uncomfortably hot for a few hours.

The worst of it was the arrival of the dreadful khamseen, most usually in the spring. The khamseen is a very hot wind coming from the south and it inflicts terrible hardship on all. It blows down tents, fills every crevice with sand particles, prevents any cooking, and irritates the skin leaving it in a raw state. It is impossible to see more than a few yards, and after a while it completely exhausts the body and mind.

This greenish-yellow sand sticks to every inch of sweating skin, clogs hair and fills nostrils and ears. It would invade our food supplies and worst of all clog the air-fdters on our vehicles with devastating effect.

Sand was also our worst enemy when it came to keeping our weapons functioning, and the men had the task of constantly cleaning all equipment. We had a fair number of cases of sandfly fever and a few outbreaks of jaundice but neither were material. What was the real scourge was a form of blood poisoning from ‘desert sores’. For those prone to it even sunburn could trigger an attack and it was difficult to shift. I was fortunate and didn’t get any of these ailments.

The desert was full of life and most of it unpleasant. Flies were a perpetual annoyance and existed in enormous numbers, there were scorpions, fleas, lizards and ants. The scorpions climbed into bedding and boots and had a very nasty sting which could easily become infected.

Mostly the desert is hard sand, covered sometimes with scrub, some times with stones, which can vary in size from small pebbles to large boulders. It is easy to drive across and we were able to use Arab graves as navigation markers and they are plentiful.

There is an incredible beauty in the desert, especially at night under the brilliance of the Milky Way. It has a mesmerising clarity which I have never found elsewhere. During the day the escarpments, together with other physical features such as depressions, tablelands, hills and spurs, give a fair amount of variety to the scenery.

This excerpt from Desert Raids with the SAS: Memories of Action, Capture and Escape appears by kind permission of the publisher, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, copyright remains with author. The above images are not from the book.