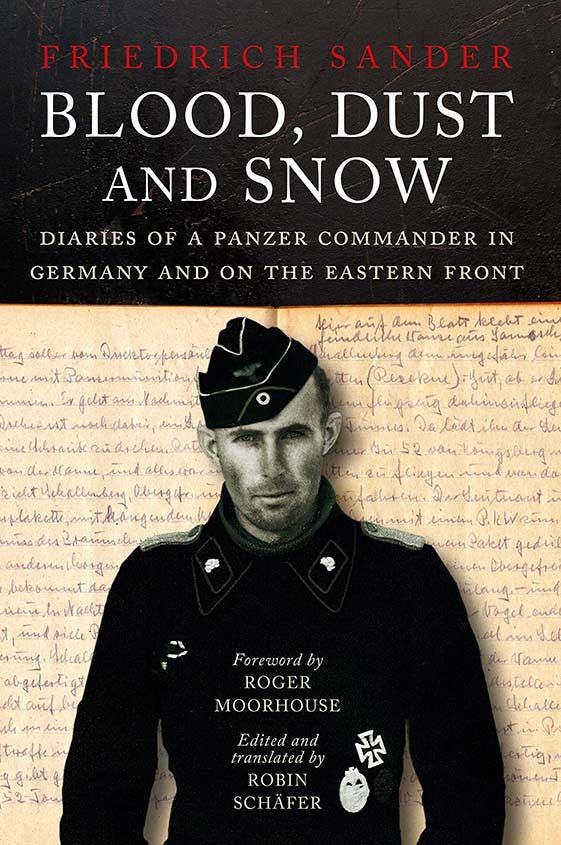

'Blood, Dust and Snow'

An exclusive excerpt from a very recently published new German account of fighting on the Eastern front

Just released - and attracting a lot of attention - is a newly found narrative of fighting on the Eastern Front. Blood, Dust and Snow: Diaries of a Panzer Commander in Germany and on the Eastern Front, 1938-1943 is a graphical first-hand personal account.

Friedrich Sander was a committed diarist, a keen observer and thoughtful of the historical significance of his role. For example, in the opening days of Barbarossa, although often exhausted after days in action, he makes the effort to record his experiences in combat in considerable detail over several pages.

Sander was a product of his times, a believer in the Nazi cause and imbued with its racial attitudes. But this is an unfiltered diary - not a memoir - and tells the story of his attitude at the time. As such it can rightly claim to be an important historical record.

The diary reveals how Sander’s outlook changed over time. The following excerpt comes from the end of the Barbarossa campaign, as the Panzers stall before Moscow. He finds himself leading his men as a reserve infantry platoon, when his Company ran out of operational tanks - all ‘lost to mines or burned out’. The temperature falls to minus 20, and still things get worse:

04.00, Tuesday, 9 December 1941, at Woronina near Klin

Since yesterday, I have been feeling a great amount of compassion for the great Napoleon who, undefeated as he was, was forced to withdraw from Russia! I have now lived to see a similar withdrawal, a smaller version maybe, but one that couldn’t have been much worse in his days. My mother used to tell me stories about the French and their allies, how they were forced to wrap rags around their feet and how they put on women’s skirts just to keep warm.

Well, now I have had that experience myself! Yesterday we were morally defeated, just like Napoleon’s victorious troops were. We were forced to retreat. We, the former Panzer men, had been sent from Gzhatsk to this place, to cover our retreat and to torch villages!

Yes, we have turned into proper murderous arsonists. Fucking hell, I have had enough of this. But one thing after another, this time I can’t even calm my anger through writing.

Our divisions operating on the left flank who, still motorised before the mud period set in, had managed to reach the Dmitrov Canal and crossed - together with our 6. Panzer-Division - had been forced to fall back to a defensive line in front of Klin.

Six fresh Russian divisions then pressed towards our bridgehead at Klin and south of it, all of them excellently equipped Siberian formations. The 30th Russian Army is pressing towards Spaskoye along the Rollbahn. Klin, Rogachevo, where we stood in the previous nights and the river crossing at Woronina. That’s all I know of the general situation here, north of Moscow.

On Sunday we were relieved during a fierce snowstorm. At about midday we were ordered to prepare the village for burning and to make ourselves ready to withdraw to Woronina. A distance of more than 20 kilometres which we would have to cover. I only realised in the afternoon that it was a Sunday, and it felt like mockery when I informed the men about it.

Rogachevo and the villages in front of it had changed hands several times in the previous night. Now they were still defended by our rearguard. Any vehicles we couldn’t take with us any more were blown up and all houses were put to the torch. We received the order to do the latter to our village as well.

At 15.30 it was getting dark and we started loading our baggage onto the lorries of the company. At 16.00 the first vehicles set out from Bogdanabo towards the rear. Stern remained in the village for a while and during the night requested support from one of our platoons because 6th Company had reported that Russians were advancing from the north. As such only two of our platoons remained in the small village, while Matussek and his men were sent to Bogdanabo. Wunsche, I and our platoons remained in our small village.

We were supposed to withdraw during the course ofthe night, at the latest in the early morning at 06.00, after the infantry companies with their baggage had passed through. Then the houses were to be torched and I, with my platoon, was to form the rearguard until we had reached Ssafregino, from which 6th Company would withdraw once we had passed.

Everything went as planned, until Hille panicked and, in his fear, torched the house that had been allocated to him early, just in the moment when the first self-propelled anti-tank gun rolled into the village. What a stupid thing to do! Hille didn’t want to lose connection to the infantry, no matter at what cost, and had then quickly driven away in his Kubel.

The house was burning so fiercely that the horses of the columns moving into the village would not walk past and were forced to wait until the fire had died down. But that didn’t happen. The strong wind fanned the flames and soon all the other houses, which had been allocated to our platoon, and had already been packed with hay and doused with petrol, were burning brightly as well.

We walked in between the burning houses, and through fines ofwailing women and children, towards the end of the village, where Hille was waiting, anxious to get to Ssafregino as quickly as possible.

In Ssafregino it was Eggers who panicked, and set fire to the houses way too soon, long before we had even managed to march through the village.

In school we learned about the Vikings, how they had put whole fishing villages to the torch. We have learned about the Thirty Years War, and the suffering of the population whose cities, towns and villages were burned by inhuman, marauding soldiery. So many fires that the whole night sky was illuminated by their blood-red glow. In East Prussia the people still remember how the Russians burned down the villages during the World War.

All that we have now lived through ourselves. We have seen the horrified faces of the wailing women and heard the miserable cries for help of the old men. We have seen the livestock running around in fear, heard cattle and horses screaming in terror. We have seen mothers with their children, too terrified even to speak - and now we know how a German soldier feels when he, according to the hard laws of war, is forced to commit such brutalities himself!

18.20

Just now the Russian artillery has placed a few big lumps right in front of our noses, so close that we could hear the splinters whistling. Then we all had some aquavit, the most excellent vodka. Matj Mamm, or ‘Matka’ as she is called here, lit a fire which emits volcanic heat. And now I sit here at the table with the card players near the petroleum lamp. What shall I write about? Yes, I forgot to write about the march to Woronina. The wind blew the snow into our eyes ...

Alarm!

This excerpt from Blood, Dust and Snow: Diaries of a Panzer Commander in Germany and on the Eastern Front, 1938-1943 appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.