'An Eagles Odyssey'

25th June 1941: A Luftwaffe Pilot describes dive bombing on the Eastern front

Johannes Kauffman flew with Luftwaffe from 1935 to 1945 during which he flew 212 combat missions on the Eastern Front, Stalingrad, Arnhem, the Battle of the Bulge and the Battle for Berlin amongst other theatres, flying mainly the Bf 110 and later the Bf 109. He was lucky to survive when so many of his colleagues did not.

His memoir An Eagle's Odyssey: My Decade as a Pilot in Hitler's Luftwaffe was first published in 1989 and in English in 2019. It is the ‘simple and straightforward account of an ordinary pilot’ which describes the technical business of wartime flying in considerable detail but has less to say about his personal outlook or the conduct of the war in general.

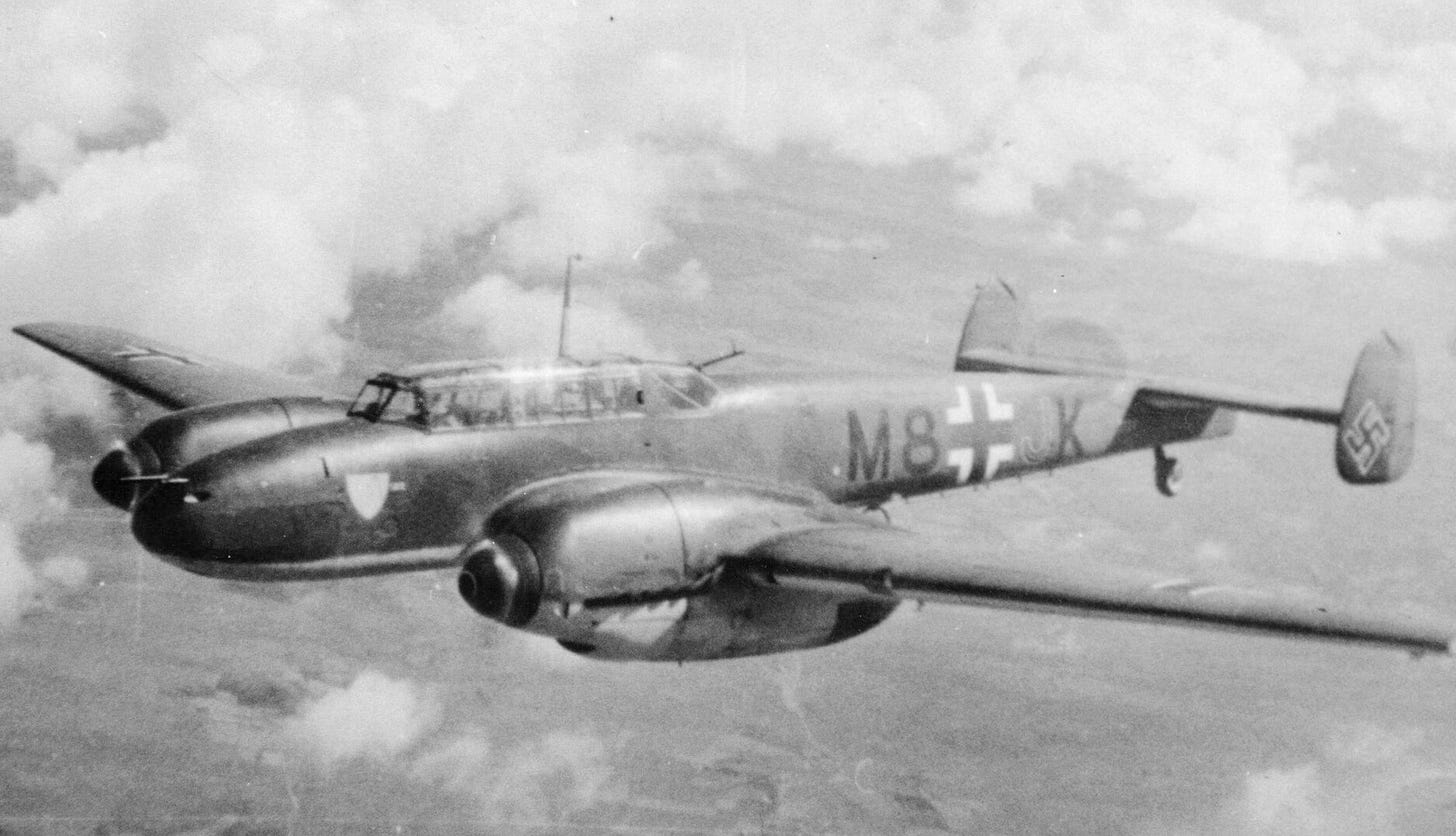

In this passage he describes flying the Bf 110 as as dive bomber in a ‘ground support’ role on the Eastern front on the 25th June 1941. This was the first of many such sorties he would fly over Russia.

The Bf 110 was not really designed for this role, unlike the Ju 87 Stuka, and pilots received limited training, so much learning was gained from operational experience. Yet this was a crucial role for the Wehrmacht, with the air superiority of the Luftwaffe and its ability to intervene on the ground battlefield proving decisive in many of the early encirclement battles.

But after just twenty minutes in the air we could already see the huge columns of dust being churned up by our armoured units as they advanced along the unmade Russian roads below us, while the clouds of black smoke darkening the horizon ahead were a sure sign that we were rapidly approaching the scene of the fighting. The nearer we got to the battlefield, the more intense and confused the activity on the ground became.

Tanks and armoured personnel carriers were milling about seemingly haphazardly in all directions. It was for all the world as if someone had disturbed a giant ants’ nest.

We were expecting some kind of reaction from the enemy, either fighters or Flak, at any second. I could feel the tension mounting. But we had to focus our minds on the job we had been sent out to do. While my wireless-operator scoured the skies for the first sign of Russian fighters, I concentrated on navigating and reconnoitring the ground below.

I also had to keep a constant eye on the leading pair of our Schwarm to make sure that we didn’t become separated. Although it was imperative that we didn’t lose sight of each other entirely, I nevertheless maintained a respectable distance between us.

We were flying slightly higher than the two machines ahead of us. There were three good reasons for doing this. We didn’t want to get in each other’s way when it came time to dive. It enabled one pair to go to the aid of the other if either was attacked by enemy fighters. And it meant that we didn’t offer too bunched and tempting a target to the Soviet Flak gunners, who were already starting to bang away at us with some vigour.

At first the spot that we had been ordered to dive-bomb presented a totally chaotic and confusing picture. So we circled the area a few times desperately trying to sort out friend from foe. This spurred the enemy gunners to even greater efforts. They were letting fly with everything they had by now. But their aim did not match their enthusiasm. We suffered no damage and their wild firing merely served to betray their positions to us.

Once we had got the situation on the ground firmly established in our minds, we opened out and started to climb in preparation for the attack. After a brief exchange over the R/T with our Schwarmfuhrer, we positioned ourselves ready to dive on what we had identified as the leading group of enemy tanks.

We followed each other down in rapid succession. I hardly had time to register the explosions from the leading pair before releasing my own bombs. If the mushrooms of black smoke and flames were anything to go by, our aim must have been spot on.

Pulling out of our dives at around 500m, we immediately got into line-astern formation - each machine some 300m behind the one in front - and executed a wide, flat turn ready to go in and strafe the area we had just bombed.

Now that we could see for ourselves exactly what was happening on the ground, we carried out a series of low-level strafing runs.

These demanded the utmost concentration on the part of the pilot, and a high degree of teamwork between pilot and wireless-operator.

During the initial dive-bombing phase of the attack we had spoken hardly a word. But now two pairs of eyes were needed to scan the ground racing past below us in order to spot the carefully camouflaged troops, vehicles and defensive positions concealed about the battlefield. There was thus a constant exchange of information between the wireless-operator and myself as potential targets were glimpsed and their locations reported.

Such low-level strafing attacks were, by their very nature, always very risky - but not necessarily always successful. If an aircraft was seriously damaged this close to the ground its crew stood very little chance of survival. A botched strafing run could also alert the enemy to an attacker’s intentions.

Even this early in the campaign it was already becoming all too clear that - unlike most other troops, who very sensibly took cover when attacked from the air - the rank and file of the Red Army had the annoying habit of standing their ground and firing back with every weapon they could lay their hands on. So if a pilot was foolish enough to repeat the same run twice, he would be faced with a veritable curtain of lead as the enemy troops let loose with everything they had at their disposal, from pistols to heavy machine-guns.

This is why we had been given strict orders to remain at low level after completing our first run and continue flying on the same heading until out of sight of the enemy. Only then could we turn and come in again from a different, and hopefully unexpected, angle. The obvious disadvantage to this, of course, was that it was extremely difficult to find the same camouflaged target again a second time without wasting too much time searching - especially in this hilly wooded terrain that stretched for many kilometres in every direction.

We would therefore decide upon a different angle of approach, climb to about 300m and start a new run, making course corrections as we did so. With the element of surprise gone, jinking about at low level trying to line up our sights on the target, and flying through an absolute hail of fire - the likes of which only someone who has actually experienced it could possibly imagine - it was little wonder that we collected innumerable holes in the fuselages and wings of our aircraft.

In all we spent a good forty minutes over the target area, from the time of locating and identifying the enemy’s positions until breaking off the attack and returning to Radzyn.

When we got back we reported to the ops room for debriefing. As we hadn’t had the opportunity to take any photographs while over the target area, we had to rely solely on our own impressions and observations to describe the attack.

This excerpt from An Eagle's Odyssey: My Decade as a Pilot in Hitler's Luftwaffe appears by kind permission of the publisher, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, copyright remains with author.