This week’s excerpt comes from a new study of Alistair Maclean, the man behind ‘The Guns of Navarone’, ‘Ice Station Zebra’ and ‘Where Eagles Dare’ among many other popular novels - only some of which have yet been filmed. The author focuses on Alistair Maclean’s experiences in the Royal Navy - on the Arctic Convoys, in the Aegean and in the Far East - and how they influenced his writing.

This is not a full biography but develops a picture of life in the Royal Navy drawn from Maclean’s and others’ wartime service. The fate of various Arctic Convoys informed Macleans first record breaking best-seller ‘HMS Ulysses’ - including his time on HMS Royalist during convoy escort duty in early 1944. And there is a lot of fascinating background about the fictional island of Navarone. Also included are two full short stories, demonstrating his great talent for compelling fiction

The following excerpt looks at some of Maclean’s non fiction writing:

‘These six stories have a similar theme highlighting incompetence, bureaucratic nonsense and interference from Whitehall coupled with heroic self-sacrifice.’

In that same year [1960] Alistair wrote a series of articles for the Sunday Express returning to the war, sea stories, most about tragic incidents. Given the events were still shrouded in secrecy at the time, Alistair asked some pointed questions.

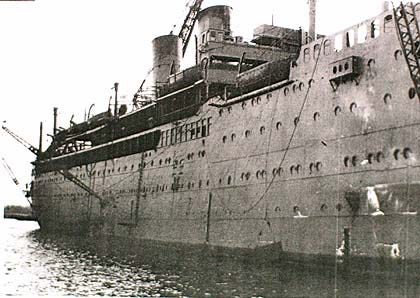

In July 1940 the Arandora Star, a Blue Star liner, had been taking 1,600 German and Italian internees and some prisoners of war to internment camps in Canada. Two days out of Liverpool she was torpedoed by a U-boat at 0600 hrs. The submarine was U-47 commanded by Gunther Prien, one of the most successful U-boat commanders of the war. He had managed to get into Scapa Flow and had sunk the battleship HMS Royal Oak.

Alistair is scathing about the press reports at the time that blamed the large loss of life on the cowardly behaviour of the Germans and Italians. One report even had thirty Italians fighting among themselves 'for theprivilege of sliding down a single rope’. However four survivors were interviewed, two crew members, one Italian, and a British passenger, all agreed there had been no fights or panic to get to the boats.

‘Alistair asked the question: why the bad reporting? He felt the papers had doctored the information to try and explain the great loss of life, maybe, even under official direction.’

Alistair asked the question: why the bad reporting? He felt the papers had doctored the information to try and explain the great loss of life, maybe, even under official direction. He then goes on to explain in some detail the reasons for the cover up. The captain ofthe ship and the CO of the guard had both protested about the overcrowding on board and wanted the passengers cut by half.

Naturally the overcrowding meant there were not enough life-jackets; if there were not enough life-jackets there were not enough life-boats and there had been no life-boat drill either. Life rafts that might have saved lives could not be released because the tools needed to do this were not available, so they went down with the ship.

Something that did not come to light until sometime later was that barbed wire compounds had been erected onboard. These partitioned the decks and cut access to the lifeboats. Captain Edgar Wallace Moulton protested but the wire remained.

There was little wonder that the story of the Arandora Star was placed under a blanket of official secrets. Nevertheless about 1,000 people, guards, crew and prisoners got off the sinking ship. Although July, the Atlantic was bitterly cold and people began to die.

Around noon a Sunderland flying boat came on the tragic scene and helped guide the Canadian destroyer St. Laurent there. She searched the sea for hours using her boats and keeping on the move, well aware U-boats might still be in the area and they managed to pick up 800 survivors.

Alistair called it:

‘an astonishing feat almost without parallel in the life-saving annals of the sea, almost enough to make one forget, if even only for a moment, the barbed wire and the thousand men who died. Almost, but not quite.'

These six stories have a similar theme highlighting incompetence, bureaucratic nonsense and interference from Whitehall coupled with heroic self-sacrifice. They would hardly have been looked on favourably by the powers that be at the time, only fifteen years after the war’s end.

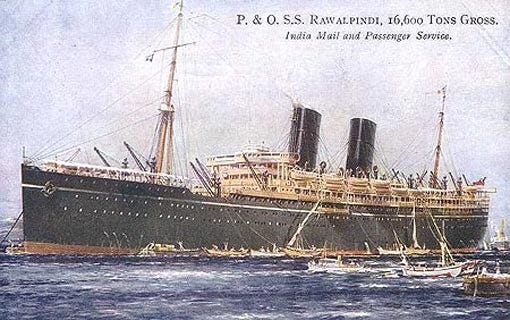

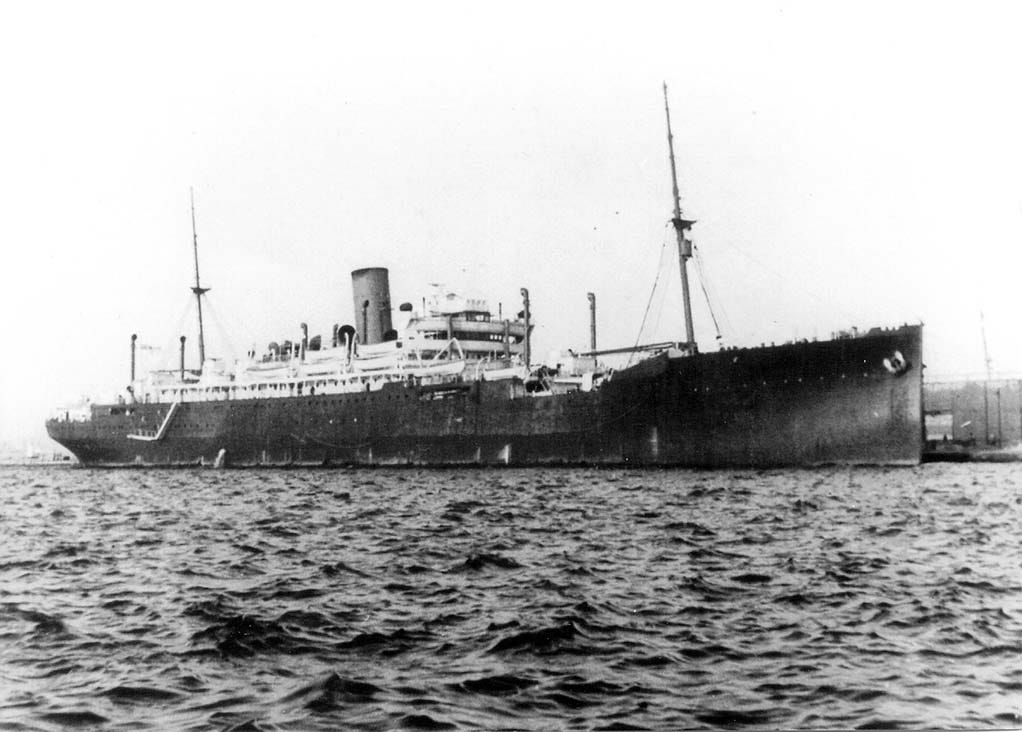

HMS Rawalpindi was a P&O liner built to ply between Britain and the Far East. Pressed into service as an armed merchant ship because of the Royal Navy’s lack of cruisers, the 17,000 ton ship had eight old 6-inch guns, a crew of 280 made up of about fifty men who had served on the ship before the war, the rest were RNVR, and there were no regular navy on board. Rawalpindi and ships like her were deployed on the Northern Patrol around Iceland and Greenland to stop merchant ships trading with Nazi Germany. She doesn’t get the signal to withdraw when two German battle cruisers steam into her patrol area.

The Scharnhorst signalled HMS Rawalpindi to ‘Heave to’, but Captain Edward Coverley Kennedy, called back by the navy after seventeen years ashore, refused. Within minutes HMS Rawalpindi is a flaming wreck but still managed to hit the Scharnhorst. Yet the sixty-year-old Captain Kennedy, almost like a MacLean character - although this was for real - would never admit defeat, his bridge wrecked around him he leaves looking for some smoke floats to cover the ship’s escape: His ship was holed and sinking, damaged beyond help or repair and visibly dying: his guns were gone, his crew were decimated, but still he fought for survival.

It was a display of "courage’ and 'tenacity in some ways beyond comprehension.’

The Germans picked up forty men, 240 went down with HMS Rawalpindi including Captain Kennedy.

The story of HMS Jervis Bay was another armed merchant ship, the only cover for convoy HX 84 out in the mid Atlantic, before the U-boats had really developed into the threat they were to become. It was 5 November 1940; Britain had survived the threat of invasion. The convoy consisted of thirty-seven ships including eleven tankers. The sole escort had been built in 1922 and was armed with some old 6-inch guns, commanded by the Irish Captain Fogarty Fegen, the 47-year-old son of an admiral.

It is evening and over the horizon comes the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer, 10,000 tons, fast and armed with six 11-inch guns. The convoy is ordered to turn to starboard away from the threat and to scatter and make smoke. Meanwhile HMS Jervis Bay turns toward the enemy and puts on speed to close the range; she is soon hit.

Admiral Scheer moves to bypass HMS Jervis Bay but Fegen alters course to intercept to keep his ship between the enemy and the convoy. Pounded by the 11-inch guns she was quickly wrecked as a fighting ship. Again Admiral Scheer tries to move around but the impudent ship keeps coming, even though on fire with huge holes in her sides, as if she is attempting to ram the pocket battleship. Fegen by this time had lost an arm; he orders smoke floats to be dropped still trying to cover the escape of the convoy and soon after was killed. He would be awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

HMS Jervis Bay sinks stern first, the Germans make no attempt to pick up survivors. The Admiral Scheer only manages to sink five ships in the convoy. That night the Swedish ship the Stureholm, commanded by Captain Sven Olander, goes back to the scene, even though the frustrated German ship is cruising around, firing star shells trying to find other victims. She manages to pick up sixty-five survivors from the freezing waters.

The Meknes was a French ship which had onboard 1,180 French sailors who, since the fall of France in 1940, had elected to go home. She leaves Southampton at 1630 hrs on 5 July en route to Marseilles, steaming down the English Channel lights blazing, for in effect she is a neutral ship. That night an E-boat opens fire on them.

Captain Dulroc of the Meknes asks ‘Who are you?’ and the reply is in the shape of a torpedo. The E-boat even machine-gunned the survivors in the water. Almost a thousand men were left in the water and were picked up by British destroyers in the morning. MacLean asks just who was responsible for this disaster that cost 400 lives. The French claimed they had not been informed of the sailing, the British said they had:

What is beyond dispute', wrote Alistair

'and this is the crux of the matter — no safe conduct or guarantee was given by the Germans. Yet the criminally negligent decision was made to permit the sailing of this unarmed and unescorted vessel into the E-boat and U-boat infested Channel without waitingfor a reply from the Germans.

He goes on to place the blame firmly in the corridors of power and does not mince his words.

It would be interesting indeed to know what British Service or Government department was responsible for this decision.

The RMS Lancastria was more a straight Government denial at the time to keep bad news from the British people. She was sunk by German bombers off St. Nazaire during Operation Aerial, the evacuation of British troops and civilians from ports in Western France. Estimates vary ofjust how many people were on board, it is believed that as many as 3,000 people might have gone down with the ship while another 2,500 were picked up. Churchill himself put a D-notice on the sinking, the worst maritime disaster in British history. In Alistair’s article he concentrates more on the personal stories of some of the survivors.

The last of the six was the City of Benares perhaps the most tragic of all because it involved children. The City of Benares was torpedoed on the night of 17 September 1940 in the North Atlantic and she went down in just over ten minutes. Her total complement was 406 passengers and crew, 100 of which were young children; nearly all of them were being evacuated to Canada under a Government scheme. On the third day out after leaving Liverpool the destroyer escort left their charges as they were past the recognised danger zone.

Many of the children died in the initial explosion or were trapped in their cabins and went down with the ship. In the end only nineteen would survive. 'A pitiful handful', wrote Alistair. Yet dozens of the crew and passengers gave their own lives willingly to try and save them, like the man who towed a raft of children away from the sinking ship to a lifeboat. He went back for another and again a third time after which he was never seen again. Of this man Alistair wrote:

We do not know, nor does it matter. All we know is that this man who selflessly gave his own life would never have thought of recognition nor cared for it had he been given it. An unknown man, a nameless man, but he remains for ever as the symbol of the spirit of the City of Benares.

This excerpt from Alistair Maclean's War - How the Royal Navy Shaped His Bestsellers appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.

NB The above images are not from this volume.