'Airmen's Incredible Escapes - Accounts of Survival in the Second World War' lives up to its promise with a collection of previously unpublished stories, all of them extraordinary stories by men who defied the odds and lived to tell the tale. They are drawn from first person accounts by British, Commonwealth and American pilots and aircrew, covering fighters and bombers in every theatre through the war.

The following account is from RAF Flight Lieutenant Lewis Bevis who was posted to Egypt in September 1941. First he had to fly his Hurricane across Africa to get there!

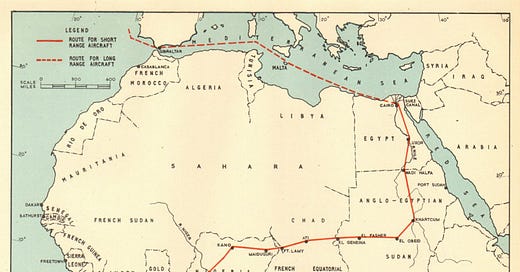

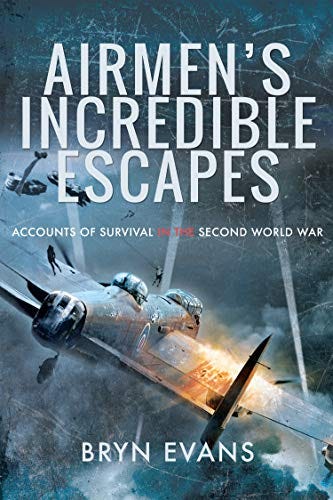

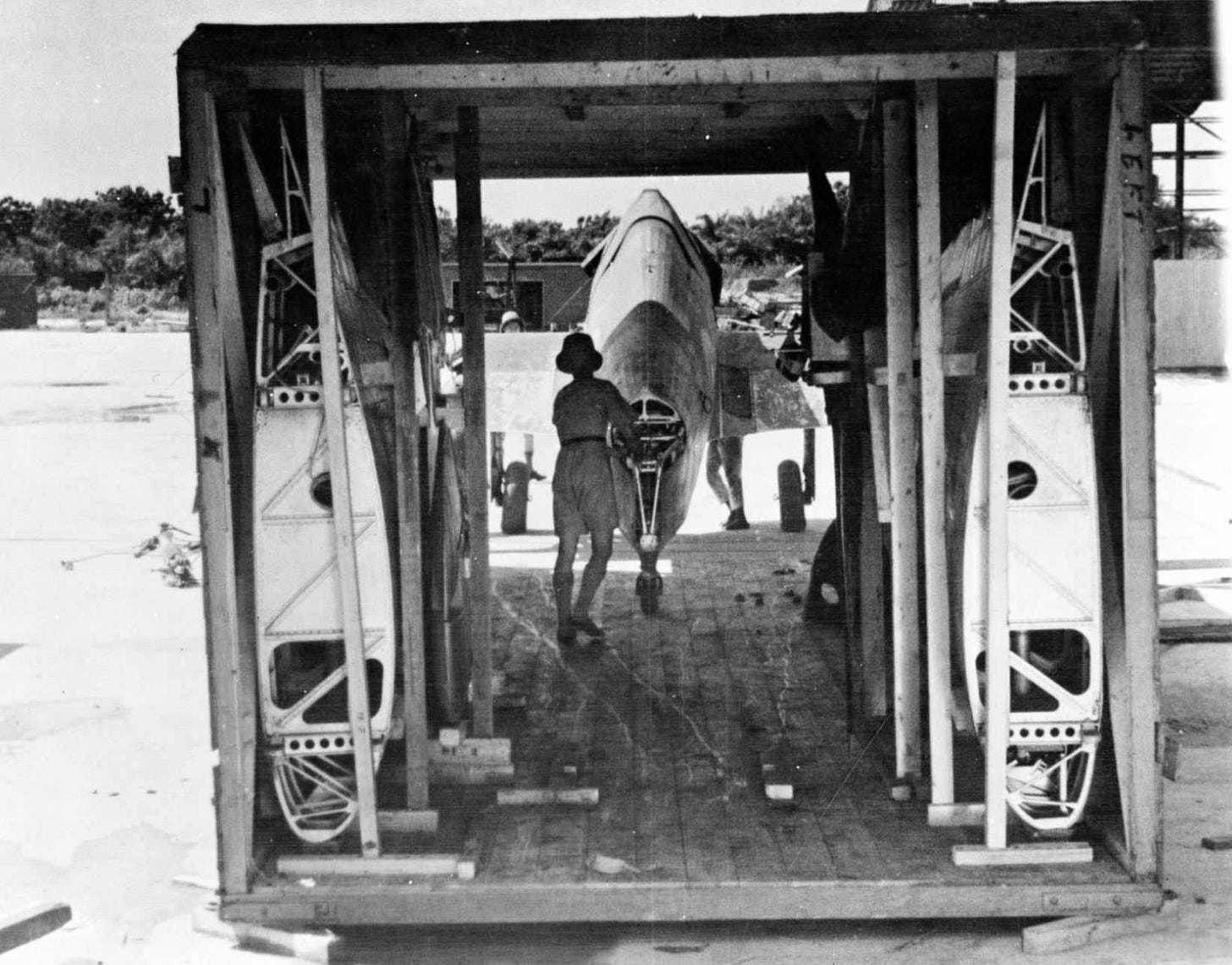

With the Mediterranean especially hazardous for convoys to Malta, let alone all the way to Egypt, most supplies fro the British in the Middle East went all the way round Africa and up the Suez canal. For aircraft a quicker option was to take crated planes to the port of Takoradi on the west African coast, assemble the planes there and then fly them east and then north to Egypt in a series of hops.

‘After a week or two of training and acclimatisation at Takoradi, Bevis took off in a flight of six Hurricanes on the first leg of the long haul to Egypt…

The first day they followed a Bristol Blenheim, which was in the lead for navigation, south to Lagos in Nigeria where they spent the night. Next morning, with the other five Hurricanes, Bevis lifted off on a four-hour flight to Kano in Northern Nigeria.

In the group with me was another Londoner, Rick. Petrol economy was important and we were instructed to fly at low revs and high boost to achieve this. After a little over an hour’s flying, I developed engine problems with a loss of performance. I fell behind the flight and was advised by the leader to make my own way.

However, Rick decided to stay with me. We were at 12,000 feet over thick cloud when I explained to him over the R/T that if I descended below the cloud I would not have enough power to regain height. He suggested that he should go down below the cloud and advise me of the terrain. Checking the course on my map, I saw that we could possibly be over mountains up to 5,000 feet, so I told him to wait.

Rick did not wait. Ten days later he was found dead, having descended into the cloud and crashed into a mountain face.

I continued on, and no longer being in touch with Rick, decided I had to try to get below the cloud cover. I broke cloud at about 3,000 feet over high ground coming out just above the treetops, luckily to a landscape falling away in front. Being on course I was able to pick up the Niger river and, in time, landed at Minna where petrol reserves in 4-gallon cans were available.

The next day Bevis, with a full tank of fuel, was able to reach Kano. The ground crew there found that the Hurricane’s engine required maintenance on its plugs, caused by the necessary over-boosting during the flight. This meant that he had to wait to join the next ferry flight of Hurricanes.

When they arrived three days later, Bevis set off with them on the various stages via Maiduguri, El Geneina, El Fasher and Wadi Seidna across the southern Sahara and Sudan. At the Wadi Seidna airfield, despite Bevis and the other pilots having been flying since 05.45 hours that morning, the station officer made them refuel and take off again on a seven-hour flight north to Luxor in Egypt.

During the flight from El Fasher, Bevis had dropped his maps on to the floor of the Hurricane, intending to recover them on landing at Wadi Seidna. Distracted by the orders of the station commander, he forgot to do so. Once airborne, Bevis found himself thinking it would be easy to follow the other five Hurricanes without his maps:

‘After nearly an hour, we ran into a sandstorm, reducing visibility to nil. We got split up and now I was on my own.’

He needed those maps, but would need to land in order to find them, wherever they had lodged in his cockpit. He made several attempts to land in the desert, pulling away at the last moment from rock-strewn areas.

Finally I noticed a native village with a clear area nearby on which I landed. I was then able to recover the maps. While I was doing this, I was descended upon by a crowd of natives from the nearby village, riding donkeys and camels. While they gathered round, I pointed to place names on the map to establish my position. The name Abu Ahmed rang a bell with them, and that apparently was where I was.

The village headman gave Bevis a bed for the night made out of ropes, and he slept surprisingly well. In the morning, by using sign language and pointing at chickens, he managed to get boiled eggs for his breakfast. However, when he reached the Hurricane, he found that the villagers had stripped it of the leather gun covers, his parachute and, among other loose items, his Very pistol, which was his only means of defence.

I started up the motor, surrounded by donkeys and camels. I had checked my fuel and the distance from Abu Ahmed to Luxor, and I reckoned I still had enough to get me there. I climbed to 8,000 feet and set course.

At a point some forty miles south of Luxor, where a low mountain chain crosses the Nile and there are river cataracts, the red fuel-warning light came on. I was shocked, very short of fuel, and wondering whether the gauges were accurate. Looking around, I saw what appeared from high up to be a roadway.

‘Although unconscious for a while I was not seriously hurt.’

However, when I got down to about 1,000 feet what had looked a suitable road from higher up was, in fact, a doubtful surface with banking on each side. Committed I made a good landing, but unfortunately hit a large boulder. This turned the aircraft off the road and onto its back, and I passed out.

Although unconscious for a while I was not seriously hurt. Eventually an Egyptian, an educated engineer working on the Nile, came to help me. He took me to a telephone. After some hours a truck arrived from Luxor with airmen seeing what they could recover from the Hurricane.

Bevis then returned to Luxor with the recovery crew, and in a few days was allocated another Hurricane in a group flight to go on to Cairo. On this last leg of the journey I flew into a khamsin sandstorm. The desert sands are lifted by gale-force winds to heights of 10,000 feet. It gives you the impression of being just above the ground temporarily raised to 10,000 feet.

In the poor visibility once again I became separated from the rest of the flight. I climbed above the sandy murk to work out a plan, knowing that I required sufficient fuel to make a precautionary landing if necessary. With this in mind I decided that the best course was to try to land while I still had petrol in hand.

‘At around 800 feet I suddenly noticed the colour around me changed from a reddish-brown to grey. This turned out to be the ground coming up!’

Bevis dropped the Hurricane down into the sandstorm’s higher clouds. Immediately he could not see anything at all. There were no breaks in the cloud at all. All he could do was to continue to descend steadily by circling turns, all the while watching the air speed, gyro instruments and altimeter.

At around 800 feet I suddenly noticed the colour around me changed from a reddish-brown to grey. This turned out to be the ground coming up! I levelled off, and landed into a 40mph wind. I rolled no more than a few hundred yards before coming to a stop. I began to get out of the aircraft to look around, but as I was dressed only in shorts and a sleeveless shirt, I found the gritty wind stung too much, so I stayed in the cockpit. It was about 15.00 hours. As the evening drew on, the storm abated as is usual in a khamsin. I took a look around in the dark, returning to the aircraft to try and get some sleep sitting up.

In the morning Bevis was able to walk around and inspect the area where he had landed. The storm began to regain its tempo, and he knew he needed to take off again soon.

I had landed in a small wadi with soft sand scattered through it. I started the engine and taxied to the far end. Several times the wheels sank ominously into the sand, making it feel as if the aircraft must go up on its nose. I then realised I would have to prepare a path. I began laying flat stones to try to make a firmer surface for take-off.

It was tedious backbreaking work. The temperature rose above 100. What little water I had in my flask I sipped economically throughout the day. By evening my confidence was slipping. I knew I was in for another night in the cockpit. I continued to gather stones for the take-off that I had put off to the following morning. I also knew I was beginning to dehydrate.

Bevis’s ordeal only ended with a great deal of luck and some prayers when he eventually managed to take off and fly to a landing strip in Egypt. He was taken to hospital to recover before completing his journey to Cairo.

This excerpt from Airmen's Incredible Escapes: Accounts of Survival in the Second World War appears by kind permission of the publisher, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, copyright remains with author. The above images do not appear in the book.