'Airborne Warfare 1939-1945'

A Photographic History

A Photographic History of Airborne Warfare 1939-1945 - published in 2021 - is a comprehensive overview of paratroop and glider borne troop operations in World War II. It covers all the different forces that had this capability during the war - mainly German, British and American but also encompassing Russian, Japanese, Australian and others - and how these troops were actually used.

Along with the other books from this series by Simon and Jonathan Forty it features a huge range of photographs and other images all with knowledgeable captions, as well as an explanatory text. A really good single volume introduction to airborne warfare. Enthusiasts will have seen many of these images before, but probably not all of them.

The following excerpt deals with the pre war development of Airborne warfare beginning with the true pioneers - the Russian Army:

‘The airdrop required the true daredevil air warrior - someone tough, resourceful and confident enough to fight behind enemy lines and crazy enough to jump out of aeroplanes in the first place.’

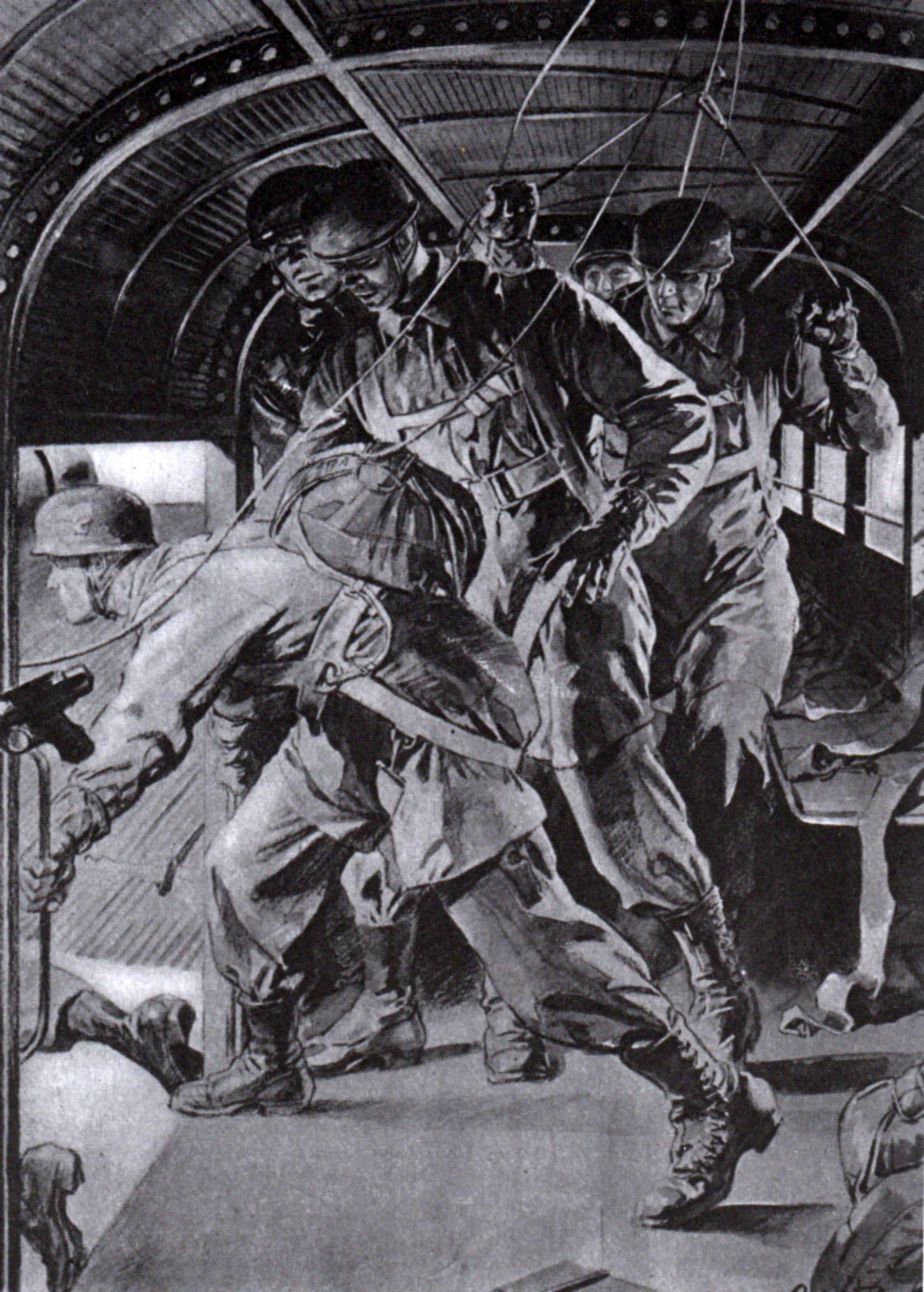

They began to evolve two main types of operation: the airdrop into enemy-held territory using parachute or glider and the airbridge, which required a captured airfield for continuous resupply of more conventional troops by air.

The airdrop required the true daredevil air warrior - someone tough, resourceful and confident enough to fight behind enemy lines and crazy enough to jump out of aeroplanes in the first place. (All the paratroop units of the different nations began with completely voluntary recruitment appealing to this kind of fighter)

The airbridge required the development of an airborne landing detachment consisting of a rifle company, sapper; communications and light vehicle platoons, a heavy bomber squadron and a corps aviation detachment

By the mid-1930s the Soviets had a substantial and dynamically evolving airborne force of almost 10,000 men and this led to a showcase demonstration of future warfare that stunned foreign military observers, when in 1935, the first live airborne airdrop witnessed two full battalions of paratroopers with light field guns landing in under ten minutes to seize their objective. Exciting though this was to military theorists its aggressive implications ensured that it did not long survive an initial burst of interest, for the western states were tired of war and really only interested in defence.

The British thought such an airborne attack force was at odds with the defensive requirements of empire, the lack of heavy equipment limiting it to the role of mere saboteurs. The French experimentation consisted of two parachute companies created in 1937 who would form the basis of their later airborne effort post-1943. Fascist Italy conducted early experiments in the late 1920s, culminating in the 1941 formation of a 5,000-man parachute division designated the 185th Parachute Division Folgore, whose destiny was to end up serving as ground troops.

But for the Nazi regime in Germany, secretly rebuilding its armed forces and searching for new methods of warfare, the Soviet airborne demonstration was an epiphany and they immediately set about forming their own paratroop forces. Unfortunately for the VDV the demonstrations of 1935 and 1936 were a premature high watermark, for in a paranoid fit Stalin began a series of political and military purges against everyone he felt threatened by.

The effect on the Soviet military was as devastating as any Blitzkrieg and would hamstring the Red Army for some years as those with any vision and ability were swiftly eliminated. The airborne forces were not disbanded, but more fast moving events were soon to skew their intended role.

Just as Heinz Guderian, the father of the Panzerwaffe, followed closely all armour developments worldwide to synthesise his new combat formula, so too did the soon-to- be father of the Fallschirmjager; Kurt Student, with all matters aeronautical. Student was a veteran WWI pilot assigned to military research who had spent time in the USSR observing both glider and parachute development.

After witnessing the Soviet demonstration in 1935 he returned to Germany to join the secretly reestablished Luftwaffe and play a key role in developing Germany's glider and parachute capability. In 1938 he assumed command of all airborne and airlanding troops and became commanding general of Germany's first paratroop division, a role he would continue for the war's duration.

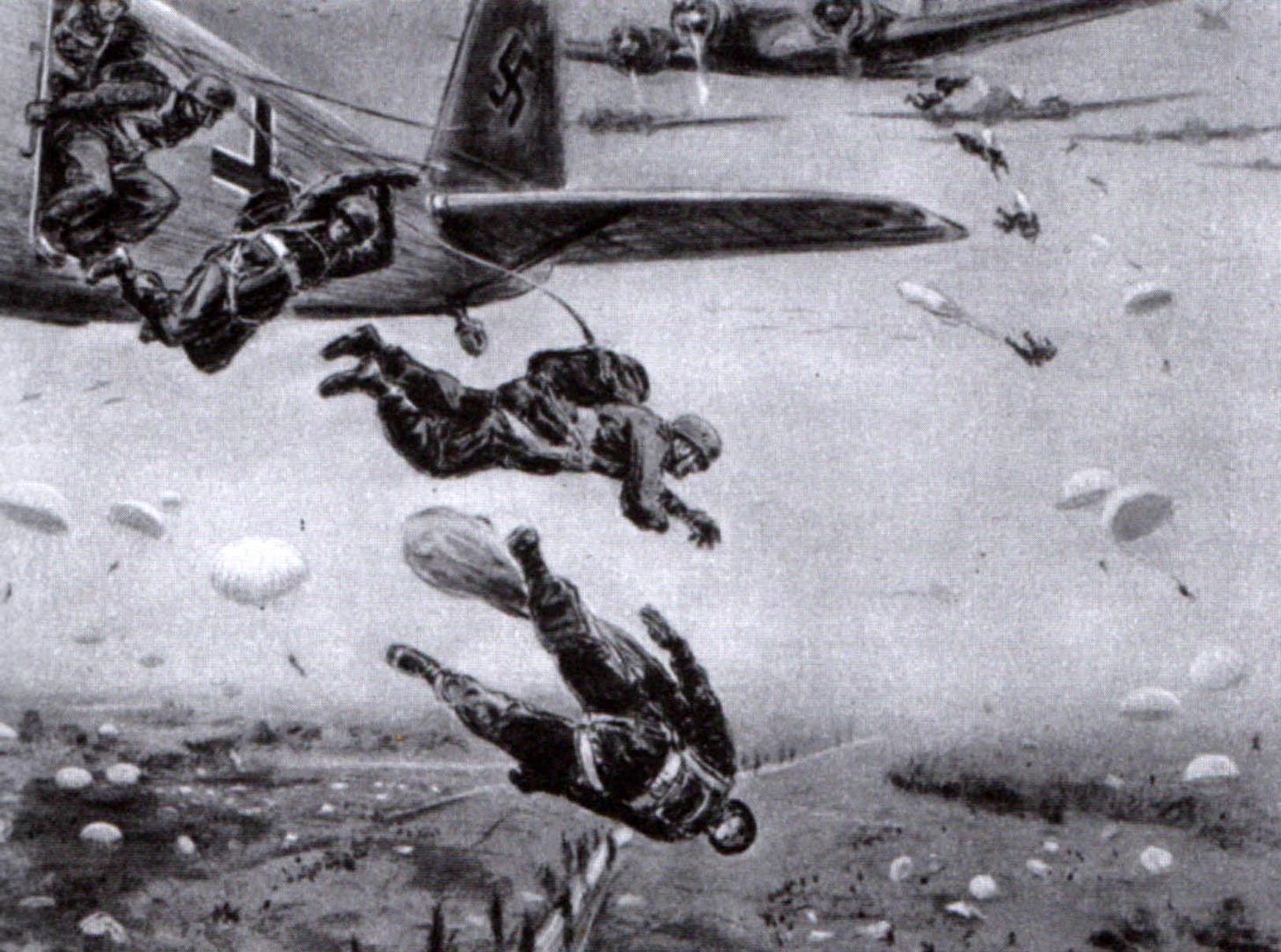

In conjunction with the Luftwaffe's development ofthe Fallschirmjager and their delivery systems, the Germans began creating supporting formations that could reinforce them once an aerial bridgehead had been established. These other elements were transported primarily by Junkers Ju52s, but also used gliders.

With fierce enthusiasm and efficiency that made the process fast, the Nazis created effective airborne forces with both airdrop and airlanding capability. In 1939 on the eve of war; only the USSR and Germany possessed such airborne troops.

It seems puzzling in retrospect that Britain and the United States had little real interest in developing their own airborne forces. This was a decision they were just about to deeply regret, for they would soon be frantically trying to catch up, starting virtually from scratch and actually during hostilities. Two brand new military formations the Panzenwaffe and the Fallschirmjager were about hit the world stage and blaze their brief trail across history.

This excerpt from A Photographic History of Airborne Warfare 1939-1945 appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the authors.