A Prisoner of Stalin

A Luftwaffe Officer 's memories of being captured on the Eastern front

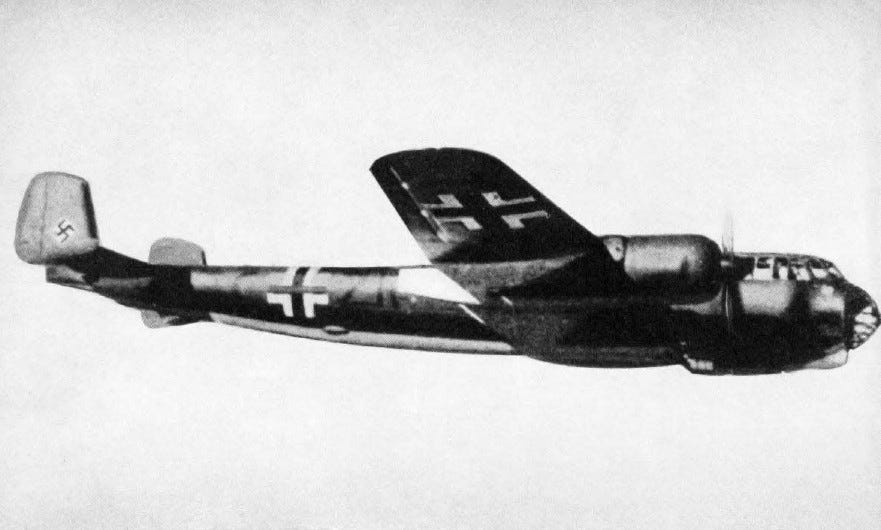

Leutnant Gerhard Ehlert was a Dornier 217 night-time reconnaissance pilot operating over the eastern front. His missions were to take photographs of Red Army troop concentrations, illuminated by dropping flash-bombs. Navigation across the expanses of Poland and western Russia was a demanding business at night, reliant on locating known features such as rivers and railway lines. In time their flights became predictable.

Ehlert was shot down and captured by the Red Army in 1944 - and did not return to Germany until 1949. It was only in 2014 that he recounted his story to journalist Christain Huber. The result was A Prisoner of Stalin - a ghost-written memoir that reads like a novel. Only recently published in English, this is an account not only of the terrible conditions of Soviet captivity but also tells Ehlert’s family story and the context of how a German family found themselves at war under a Hitler they did not support.

The following excerpt takes up the story when Ehlert and his fellow airman Burr are on the run in the forests of Russia and come across a settlement in the woods:

The woman with the red head scarf greets him in a language he has never heard before and which has nothing in common with the Russian he knows to some extent. Ehlert answers 'dobre djin', good day, just as he was taught. And then the woman with the scarf finally answers him in Russian. This is almost a relief, even though he only understands a few words in this language.

Then Ehlert spits out the usual questions: ‘Soldiers, partisans nearby?’ She answers the Germans with an apparent no and says much more. With many gestures and words, the woman talks insistently to the two men, and Ehlert joins in. Somewhere he has read that as long as you talk to your ene mies, they will not kill you.

After minutes of back and forth one thing is clear: the women are evidently on their own, and the men all dead. Ehlert believes them, wants to believe them all too willingly, and Burr makes no move to be cautious, either. It is war, what worse can happen to us than death, thinks Burr, who is actually no longer able to think at all as he is much too hot despite the coolness of the twilight.

Ehlert gets the woman with the red head scarf to lead them into one of the cabins. The other women walk slowly to the two remaining huts, dust off their shoes and vanish behind creaking doors.

Bread and milk! For the first time in his life the Leutnant eats dry bread. He chews it hungrily and it tastes delicious. After a few bites and a large gulp of milk, Ehlert looks around for his Unteroffizier Burr does not want to eat anything. He is wax pale and shivering. ‘Gosh! Burr, what is the matter?’

Only now Ehlert perceives the burn blisters on the Unteroffizier’s face, which have grown into huge yellow lumps during the last few hours. Every spot on Burr’s body not covered by his uniform during the crash shows such blisters, which look like pus-filled lumps with air under a thin dome.

Ehlert looks more closely at his gunner and forces him to drink some milk at least. Burr obeys. As usual, he obeys. Then he collapses onto a bench, trembling. ‘I believe, Leutnant Sir, I cannot go on for a while.’

‘It will all be fine’, the young pilot says and is immediately ashamed of his secret thoughts: Damn it, what next? Why could Burr not take better care of himself? That is arrant nonsense, of course. Who can take care of themselves during a crash landing?

While Burr stretches out on the bench and Ehlert takes care of the piece of bread provided by the woman with the red scarf, the latter has left the cabin without a word. Again Ehlert ought to be suspicious, again he ought to urge caution, but he chews and drinks and drinks and chews and looks at the trembling Burr.

At the last moment he looks through the window and notices a silhouette flitting past. Ehlert leaps to the door and sees the boy running down the road. ‘Damn it. Something is wrong here,’ the Leutnant hisses to the room at large, and Burr slowly sits up. ‘We have to leave. Immediately!’

While Ehlert splashes his face with water from a basin on top of a dresser, adjusts his boots and his dusty, ragged uniform, Burr has taken up position at the window. Silently and with a sigh on his lips he turns to his pilot. ‘Leutnant Sir, Leutnant Sir, we are lost.’

Instinctively, Ehlert reaches for his pistol stuck in his boot leg, loads it with a cautious click and cocks the weapon. With a single look Burr drives home that this will make not the slightest difference. He shakes his head, just a few millimetres left and right, and then lowers it. Ehlert knows what this means. They do not stand the slightest chance. A loaded and cocked pistol means certain death for them both.

Ehlert lowers the pistol, engages the safety and puts it down on the table, almost tenderly. He takes a crumb of bread between his teeth, resumes his chewing and waits. As yet, the enemy is only a shadow outside the cabin. Thus far he is not real, not tangible. And yet the two men inside this log cabin at the edge of the Pripyat Marches in the middle of the Soviet Union know that the end of their freedom is standing outside the door.

It takes an endless thirty seconds, then a man opens the door with a single, violent kick. For the first time in their lives Burr and Ehlert stand eye to eye with a Red Army soldier. The young soldier looks clean and well-groomed, he is wearing a brand new uniform with a pressed appearance about it. He aims his rifle at the two Germans, and the bayonet fixed to it gleams in the light of the candles on the table in the cabin.

He is afraid. Ehlert perceives this in his eyes and he can smell it, too. The young Russian did not know what to expect inside the hut. He had to reckon on being shot down by the two Germans when entering the house. Yet no blood will flow this evening. The Russian does not let the pistol on the table out of his sight for even a moment, then he swipes it into one of the cabin’s corners with his bayonet.

‘Dawei, dawei’, he says to the two Germans. Now he seems entirely calm and relaxed. He is the victor in this fight that never happened. Ehlert will later recall not the rifle, but the uniform, this clean, pressed earthy-brown shirt, the polished boots only faintly dusty, the gleaming steel helmet. Whoever has such clean soldiers cannot lose the war.

Ehlert and Burr step out of the hut without raising their hands. At that moment, twenty, no thirty, Red Army soldiers form a semicircle around them and load their rifles. Ehlert realises that Burr has saved his life. One shot from his pistol and the entire troop would have opened fire on them and the log cabin. He does not know what weighs more in this second: the relief to be still alive or the fear of what will happen now.

.

This excerpt from A Prisoner of Stalin: The Chilling Story of a Luftwaffe Pilot Shot Down and Captured on the Eastern Front appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.