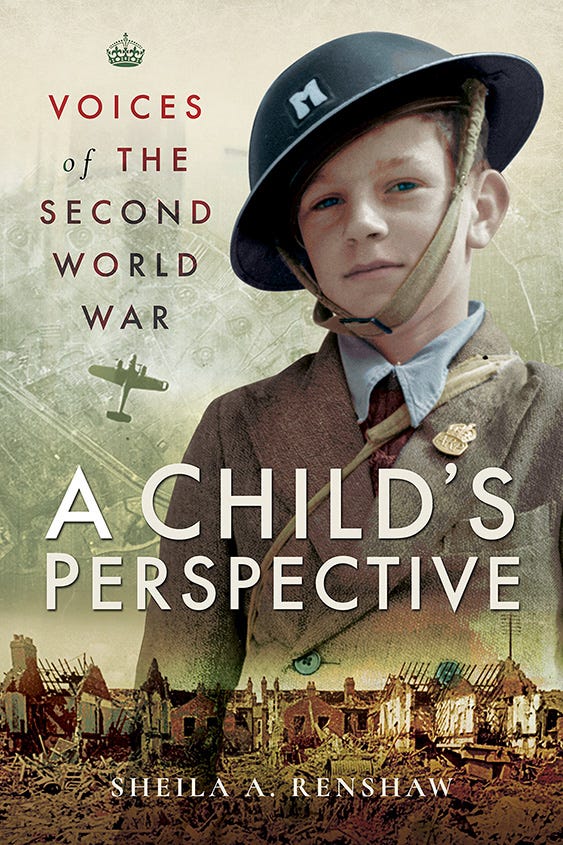

A Child's Perspective

From a wide ranging anthology of children's experiences in the war comes an account of a teenage girl living in Ukraine - when the Germans arrived

Sheila Renshaw, living in the south of England, was talking to her neighbour when she uncovered a new perspective on World War II. Nadia had never thought to tell her story before. She thought ‘nobody would be interested’ in how a 14 year old Ukrainian girl had been dragged into the service of the Germans and then taken across Europe - eventually evacuated to England when the war ended. Renshaw was so fascinated that she starting interviewing many other people who had been children during the war. The result was Voices of the Second World War: A Child's Perspective, a cross section of experiences from around Europe.

This is an excerpt from the story that started it all, the story of Nadia. She came from a small village in Ukraine but did so well at school she was sent to a college in Kharkov. When war broke out in 1941 the college closed and, unable to return home 300 miles away, she volunteered to work in a local hospital. This was the start of a long odyssey. Nadia did not return to the Ukraine to see her family until 1968.

We heard on the wireless that the Germans were advancing but rumours were everywhere and we really did not know what to expect, or believe. We heard terrible stories about how they treated Ukrainians, Russians and other Eastern Europeans. All our news, however, came from Russian broadcasts.

By this time, all the officials had deserted the town and, consequently, there was no law any more. People were frightened and desperate. They broke into stores and looted everything they could find, especially sacks of flour and anything else they could get hold of. The shops had very little left and the shelves were empty because, by this time, there were no deliveries into the town.

The hospital was a very grand building, built in the time ofTsarist Russia. It was in large, beautiful grounds far away from everyday problems. It was surrounded by a tall stone wall and had large gates. Before being turned into a hospital, it had been the summer palace for one of the Tsar’s children. One morning we were working when we heard the terrific noise of vehicles, tanks and shouting soldiers nearby. We looked out of the window and, coming across the grass towards the building, were tanks, armoured cars and soldiers everywhere.

The Germans had arrived. We were petrified and gathered together in one ward. The soldiers crashed into the room, pointing guns at us. I am not sure who looked the most frightened, the German soldiers or the nurses. The soldiers did not know what to expect. They had heard that the hospital was full of Russian soldiers. What they did not know was that all the soldiers had left several days earlier and they had retreated towards Moscow, not stopping to fight.

A sergeant was in the front, shouting at us in German. He sounded very angry and thought that if he shouted loud enough, we would understand him. After a few minutes, I decided to act. I had learnt German at school so I stepped forward and said, ‘If you stop shouting, I will tell you what our names are and what you want to know’. He was speechless and instantly changed his attitude. How could I, an ignorant Russian girl, ‘unterme-schen' (subhuman) speak and understand German? I spoke in my school girl German: ‘I am a schoolgirl but I can speak and can understand some German’.

I told him he was in a hospital. Then the door opened and an officer in a splendid uniform came in carrying a revolver. I tried to tell him we were just looking after sick people. Another older man said he was a doctor and they were going to use our hospital for wounded German soldiers. He said they would transfer all civilian patients to another hospital. We never found out where they went or what had happened to them. Even to this day I think about them.

He told us that we were to remain in the hospital as we were needed for work. He also said I could help them as an interpreter. For the next few weeks I spent more time interpreting than nursing on the wards and my German improved rapidly. A university student called Wanda was also brought to the hospital to officially interpret from Russian or Ukrainian to German. We were both kept very busy. The Germans brought women in from the neighbourhood to do some menial tasks, such as cleaning, washing bed linen and preparing vegetables.

Eventually, German army nursing sisters came into the hospital to take charge. They looked so smart in their long grey dresses, white aprons and long grey cloaks with red lining. We all thought they looked wonderful. On the whole, they treated us well but we were very aware that they were in charge and we had to do all the basic jobs. We were all kept very busy. My main job was to wash the wounded soldiers who came in very dirty with open wounds and, in some cases, in a poor condition. Stretcher-bearers brought in wounded soldiers with so many different types of wounds and burns. Some of them were so badly injured they were not even aware of what we were doing for them.

There were several different nationalities fighting alongside the Germans, so our patients included Hungarians, Romanians, Latvians and many more. The doctors were very efficient and worked very long hours and expected us to do the same. They brought medicines with them we had never seen before, mainly to fight against infection. Until then more patients died of infection rather than from their wounds or injuries.

We were like prisoners, too terrified to go out of the hospital grounds. We were warned that if anyone was caught outside, they would be robbed, attacked and possibly raped by local Ukrainians. It was much safer inside. We also heard that if the Germans found any girls outside they would be sent to Germany as slaves. It was a very frightening time. We never knew what was going to happen and just had to do as we were told. Most Germans thought all eastern Europeans were uneducated.

One evening when I had finished work and was going off duty, I was summoned to the Officers’ Mess by the surgeon I worked alongside. All the officers were sitting around a table and had just finished their meal. My doctor called me to him and told me to sit down. I wondered what I had done wrong.

Sitting opposite him was a very young SS officer. He was incredibly handsome with blond hair and blue eyes. My doctor said to me ‘Nadia this young officer does not believe a young Russian girl can be educated’.

The SS officer stood up, came round and handed me a book in German by Proust and said ‘read that,’ I stood up and the doctor told me to sit down, he said ‘Nadia, you are not in school now’. I read half a page, then he told me to translate it into Russian. This I did, then he asked me what the paragraph meant. I said that I had not studied Proust, so therefore could not give an educated explanation. The other doctors around the table applauded and the SS officer looked displeased. He said that he was amazed that I was educated at all and could actually understand a book in German.

He had a proposition for me, I could leave the hospital and work in a hotel entertain ing German officers; I would be paid, have good food and nice clothes. I was frightened and asked the colonel if I was being forced to do this. He just said to the lieutenant ‘I am sorry but I rely on Nadia in theatre. My work is of the utmost importance to the Third Reich, I am trying to save the lives of German soldiers so they can return to their regiments.’ My doctor thanked me and told me I could go back to my quarters. When I got back to my room I was still shaking, my friend said I had a lucky escape; if I had agreed, I would have been a prostitute.

The colonel was in command of the hospital, he was always kind and polite and seemed to appreciate all our hard work. That had been a terrifying moment as I did not know what was happening and everyone was frightened of the SS, they were totally unpredictable and fanatical. Nobody ever mentioned this incident again.

One of the worst things for me was not being able to contact my family to let them know where I was and that I was still alive. I had left my mother behind with three younger brothers to look after. I knew my father had been sent to the Urals to work in a factory making tanks, and my elder brother was now in the Red Army. I knew that we had a cow, some pigs and chickens and a plot of land to cultivate at home. We were part of a collective farm, so I felt sure they would be able to survive. There were no shops in the village, but neighbours were able to barter surplus produce

.

This excerpt from Voices of the Second World War: A Child's Perspective appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.