Poles join the battle in Oosterbeek

23rd September 1944: As the British paratroopers find themselves surrounded and outgunned, fresh troops are sent across the Rhine to join them

The war was five years old in September 1944. On 1st September 1939 Hitler had invaded western Poland … and then on 17th September, Stalin had invaded eastern Poland as part of an agreed partition. Soon, large numbers of educated Poles were being forcibly exiled to Siberia as Stalin took control of his conquest.

Stanisław Kulik had been fifteen at the time when his whole family were caught up in these deportations. Somehow he had survived the hard labour and the struggle to survive in the Siberian labour camps - his mother and younger brother did not.

Then, when he was seventeen, Kulik's circumstances changed with the changing war. When Hitler invaded Russia in 1941, the Poles were suddenly no longer regarded as unreliable within Russia. He embarked on the arduous and hazardous journey to join other Poles who wanted to join the Allies in the West. He travelled overland, sometimes alone, through Soviet Russia and Kazakstan before finding the British refuge for the Poles in Iraq. Then, on to India and a ship to Britain. Finally he was able to join the 1st Independent Parachute Brigade (Poland).

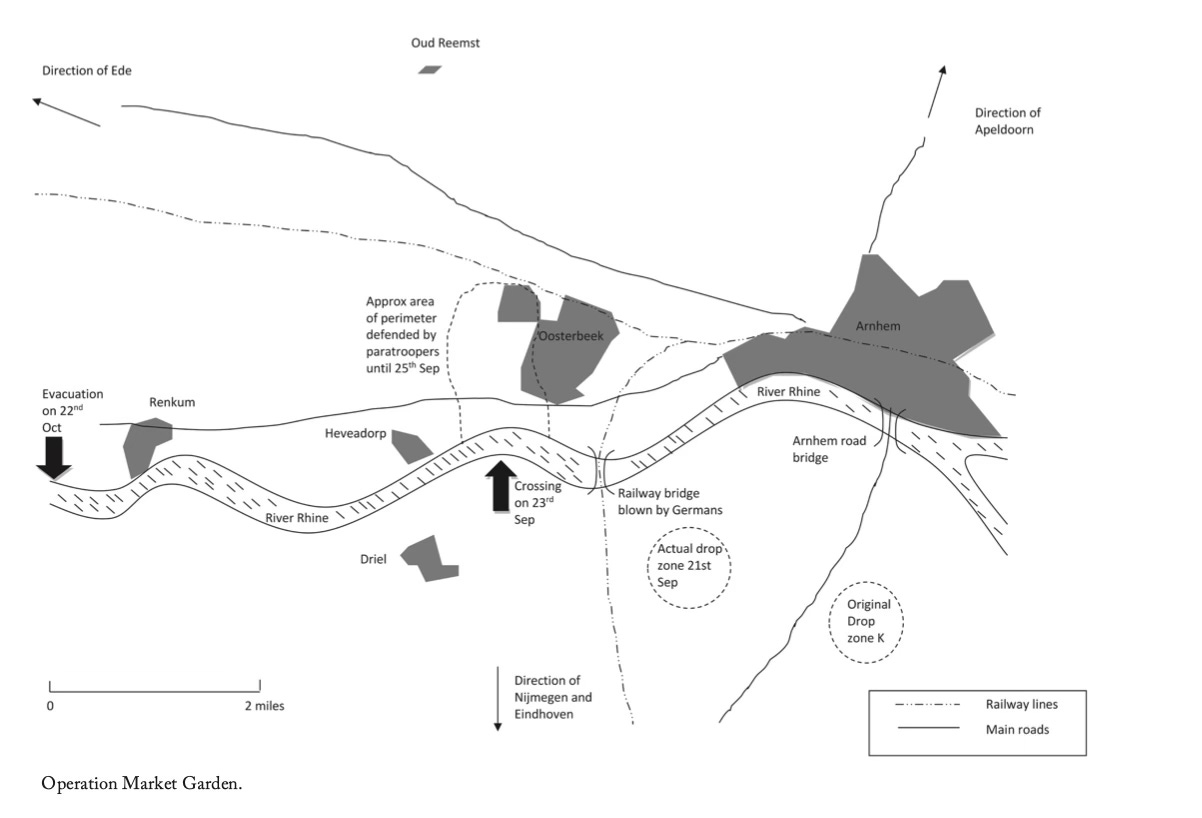

So twenty-year-old Stanisław Kulik found himself dropping by parachute into the Netherlands on 21st September 1944. With Operation Market Garden unravelling by the hour, they were still dropped south of the Rhine - but no longer would they be part of the plan to seize the bridge. A plan was now made for them to take boats across the Rhine … they would join the British paratroopers still holding out in Oosterbeek.

A stream of bullets had ripped through the water towards it, then right through the middle of the boat, the men’s bodies being sent into convulsions as the bullets hit them …

The following excerpt, from From the Soviet Gulag to Arnhem: A Polish Paratrooper's Epic Wartime Journey, takes up the Kulik’s story on the night of 23rd/24th September:

We expected to go as soon as it was dark, in order to get support over to the British as soon as possible; but it was only at about 2am, that third night, when an English officer came to collect our section. ‘It took a long time to get the boats from XXX Corps,’ was all he said, his face lit up from overhead by the flares that the Germans were sending up.

My heart was racing and we could hear the sound of machine gun fire getting louder as we walked down to the Rhine. Captain Kobak was already there, rushing about, yelling and supervising the crossing. There were a number of boats in the river.

The Germans had put up parachute flares, so that the flares dropped down slowly and gave them more time to see where we were. You could hear the roaring machine guns from the German positions on the north bank, hear the bullets fizzing past you all around and see long lines of spray being brought up from the river as the bullets hit the water.

This must be what hell looks like, I thought to myself, my heart pounding as I fought to remain calm and not panic. The situation was desperate; the boats were under heavy fire. It looked like the Germans were firing on anything that was put into the water. There were wounded paratroopers who had fallen into the river, and were trying to swim but were dragged down by their heavy equipment, or swept away by the strong current. Wounded men were screaming; unmanned boats were drifting, circling or sinking.

On the mudflats beside the river there were a few small boats that looked of questionable quality. Our section was directed towards a nearby boat and we quickly ran over to it, and started dragging it down to the south bank of the river. We jumped inside, Big Mietek and I at the front, Jurek in the middle and Bartek pushing us off from the side, before he in turn climbed in.

We grabbed what paddles there were and started rowing as fast as we could; but there weren’t enough oars for all of us and those who didn’t have a paddle rowed with the butts of their rifles. The boat was heavy and hard to control in the strong currents. The current pushed against us and we were making slow progress. Each paddle stroke hardly seemed to move us forward at all, fighting against the current, under the light of the flares above and the constant sound of the machine guns from the opposite bank.

We were sitting ducks! A bullet whizzed past my ear with a sudden high-pitched whine, and a round of bullets strafed a pattern in the water off to the left hand side of our boat. ‘We’re hardly moving!’ I shouted to Mietek.

The boat offered no protection at all from the machine gun fire as we inched our way sluggishly across the river. As we approached the half way point of the river, there was suddenly the sound of a bullet hitting something next to me; a loud ping as it hit metal and Mietek was abruptly thrown backwards in the boat.

‘Mietek!’ I cried out, and turned to him. He was lying on his back against the side of the boat. He wasn’t moving and his helmet had been knocked forward over his face.

‘Mietek!’ I called again. I stopped paddling and turned towards him, taking hold of the lapels of his army jacket. Then, slowly, he started moving. He raised his arms to his helmet, pushing it back from his face and then gently taking it off his head. He examined it closely, bringing it up to his eyes to see it better in the low light of the flares. Then, holding his helmet up towards me, he poked one of his fingers through a hole that had been shot in the top of his helmet, looking at me with a shocked expression. Then, he turned around and shouted ‘Paddle!!’ at the top of his voice to everyone in the boat and started paddling desperately with the butt of his rifle.

The landing zone was still controlled by the British, but the Germans were very near…

We all paddled. We paddled as hard as we damn well could and didn’t stop, even when we were out of breath and our arms were aching, and the seconds seemed like minutes, and the other shore could never come quickly enough. ‘Keep paddling!’ shouted Mietek frantically again.

We gradually got closer towards the other shore and it became clearer that the landing zone was a short muddy area, with a fringe of trees about ten metres back. When we landed, we scrambled out of the boat as quickly as we could and ran up the mud on the riverside to the shelter of the forest which would offer some protection. There we sat and waited, breathing heavily. We watched, as the boats behind us tried to make their crossing. There weren’t many boats after ours; I could only see two of them in the light of the flares. In the last one on the river I could see Kobak, at the back of his boat, shouting at his men to row as quickly as they could, as the bullets strafed through the water all around.

As I watched, the first boat was suddenly sent into chaos and confusion. A stream of bullets had ripped through the water towards it, then right through the middle of the boat, the men’s bodies being sent into convulsions as the bullets hit them, then either slumping down in the boat, or being sent overboard into the river to sink under the water.

‘My God,’ I said to myself, as I watched the boat now start to drift and circle aimlessly down the river, taken by the current. I could see Kobak gesticulating, paddling wildly, and shouting at the top of his lungs to the other men in his boat although I couldn’t hear what he was saying.

The men in Kobak’s boat redoubled their efforts, paddling maniacally with their rifle butts and paddles, metre by metre, gradually getting closer to us, until we could see their faces and see their expressions of effort and fear; until they managed to reach the shore, their boat running up alongside ours and Kobak and the other men jumped out and came up to join us at the tree line.

There were no more boats after Kobak’s. ‘We’re the last ones across,’ he said, trying to catch his breath. ‘Sosabowski has stopped the crossing; says it’s too dangerous.’ We had only managed to get about 150 paratroopers across, maybe a third of what we had hoped.

The landing zone was still controlled by the British, but the Germans were very near, so we needed to be careful. We had to get away from the river and find somewhere to rest. Kobak led the group of us through the forest. My ears and eyes were straining for any noise that might suggest danger. In our group there was my section and then the section that had come over in the boat with Kobak; about ten or fifteen of us in total.

It was hard going in the dark. We had to go carefully and quietly, crouching low and trying not to make too much noise as we walked through the undergrowth so that the Germans wouldn’t see or hear us. I wondered where we could be headed and whether we were going to meet up with the other Polish paratroopers, or with the British.

After some time, Kobak turned to us and said ‘let’s stop and have a rest here. We’ll see better where we are in the morning.’

We were all exhausted after the past few days, so I put my rifle between my legs and my hands under my belt and fell asleep until morning.

© Nicholas Kinloch 2023, 'From the Soviet Gulag to Arnhem: A Polish Paratrooper's Epic Wartime Journey'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd. Stanisław Kulik (1924-2016 ) did not tell his full story to his grandson until 2007 - and it was not published until 2023.