The SAS attack Kasteli airfield

4th July 1943: The raid by Danish SAS legend Anders Lassen described in an account from a recently re-released biography

Eighty years ago this week a SAS raiding party was making a forced march of over sixty miles across Crete. As the Allies prepared for the invasion of Sicily they mounted a series of covert raids to divert the attention of the Germans and destroy Luftwaffe aircraft. One of these raids was led by Anders Lassen, already known within in the SAS as a fearless leader.

The June 1943 raid was a classic SAS operation, insertion into enemy-occupied Crete to make an arduous journey on foot - while remaining undetected. The target was Kasteli Pediada airfield:

The raiders were passed from guide to guide through the apparently trackless mountains; they slept where they could - on makeshift stone beds under borrowed blankets in the mountains or hidden in the vineyards of the warmer valleys; their pouches bulged with iron rations of oatmeal, raisins and tea. Space was also reserved for tins of corned beef: “We hated it, but the Greeks loved it,” says Holmes. Villagers brought hard-boiled eggs, bread and wine, sometimes cucumbers.

All the time, the Germans were searching. Their Cretan airfields had been raided by Jellicoe and Sutherland in 1942 and they remained alert to the possibility of a return visit as well as to the presence on the island of SOE agents and marauding Allied escapees like Les Stephenson who later became one of Lassen’s first-choice men.

This German vigilance enforced the utmost caution on Lassen. For two days he lived in a cave by the airfield, a cave with an entrance hardly wider than a sewer. He and his men wriggled inside and waited for July 4, the night set for the attack. They had been on the run for almost a fortnight and only four were left to carry out the mission.

Nicholson says:

The airfield was on a steep hill and was about half a mile across. Corporal Sidney Greaves and myself were to cut the fence on one side while Lassen and Corporal Ray Jones did the same on the far side, but a searchlight swept towards Greaves and myself as we climbed the hill. We hit the ground.

I wasn’t frightened of anything in the war, not even when I was fighting in Crete in 1941 as one of only 16 survivors from No.7 Commando. I believe in mind over matter and in the powerful effects of repeating to yourself: “No pain, no pain” - as I’ve done even after an operation. But being nearly trapped by that searchlight was the closest I’ve come to being scared.

I collected my wits, though, and said to Greaves: “Start climbing again, but don’t drop down. Stand still.” We did, and the searchlight swept by without pausing. We did this repeatedly until reaching the fence. I’d realised that the operators were attracted only by movement. Anything stationary deceived them.

Eight Stuka dive-bombers and five Junkers 88s, twin-engined low-level bombers, stood on the airfield with a few fighters. Greaves and Nicholson slipped explosive time-pencils into three of the aircraft as well as leaving a timed bomb by a petrol tank; meanwhile, a small war broke out on Lassen’s side of the field.

Two Italian sentries had been killed ruthlessly by Lassen; the first silently in the approved Fairbairn-Sykes manner with a hooked grip round the jaw followed by a downward thrust of the fighting knife, and the second swiftly by Lassen firing without troubling to remove the pistol from his pocket. The knife would have suited Lassen better but he had no choice because the sentry, unlike three others he had bluffed in the cordon, was standing off and refusing to believe his claim to be German.

The shot brought the garrison scurrying from their bunkers, banishing the dark with flares and firing at every suspicious movement. Lassen and Jones ran for it. The citation for Lassen’s second MC picks up the story.

Half an hour later this officer and other rank again entered the airfield, in spite of the fact that all guards had been trebled and the area was being patrolled and swept by searchlights.

Great difficulty was experienced in penetrating towards the target, in the process of which a second enemy sentry had to be shot. The enemy then rushed reinforcements from the eastern side of the aerodrome and, forming, a semi-circle, drove the two attackers into the middle of an anti-aircraft battery where they were fired upon heavily from three sides. This danger was ignored and bombs were placed on a caterpillar tractor which was destroyed.

The increasing numbers of enemy in that area finally forced the party to withdraw. It was entirely due to this officer’s diversion that planes and petrol were successfully destroyed on the eastern side of the airfield since he drew off all the guards from that area. Throughout this attack, and during the very arduous approach march, the keenness, determination and personal disregard of danger of this officer was of the highest order.

Nicholson, though, eyes the official version with scepticism. He says:

“Andy Lassen was a brave man and a cool man. I would call him stupidly brave, except that he kept getting away with it - and sometimes I think he got credit for things he didn’t do. Kastelli airport is an example. That was no diversion, it was a bungle, Lassen and Jones were meant to be as silent as me and Greaves.”

The firing had been so intense on the far side of Kastelli that Nicholson and Greaves thought it impossible for Lassen and Jones to have escaped capture or death, so they made their own orderly return towards Sutherland’s base camp by the beach. Sometimes, they disguised themselves as shepherds with cloaks and crooks; one night they slept on a hillside among villagers in flight from the hostage-taking Germans heading for their dwellings.

The Cretans’ fears were well-founded; fifty-two hostages were shot in reprisal for the raids and a further fifty were threatened with death unless Sutherland’s saboteurs were handed over. No one came forward and, despite the risk, peasants sheltered Jones when he was separated from Lassen in their escape from the airfield. The same village took care of Lassen when he, at last, dared to show himself after two days of hiding in fields, living on raw onions and cabbage.

They gave him water, reunited him with Jones and sent them with a guide along a route where other hamlets, places of desperate poverty, waited with wine, plates of roast kid and, best of all in Lassen’s opinion, cigarettes.

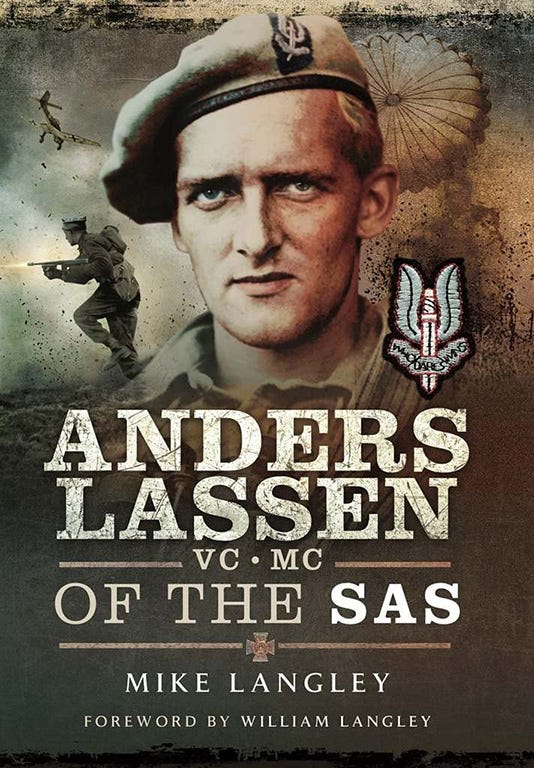

An excerpt from the recently re-released Anders Lassen VC MC of the SAS, a biography of the legendary hero from Denmark, based on many eyewitness accounts from the men who fought alongside him.

Lassen came to Britain to volunteer soon after the outbreak of war and served in the Commandos before transferring to the SAS. He participated in many operations in Africa, the Mediterranean and Italy where he soon became renowned in the SAS for his courage and determination. Relatively small raiding forces were to tie down disproportionate numbers of German troops. Even within the SAS Lassen stood out, as one fellow SAS member noted:

Once he got going he’d kill anyone. He was frightening in that way - and his view of the Germans was more personal than ours because his country was occupied.

… if he had the opportunity he’d kill someone with a knife rather than shoot…

This excerpt from Anders Lassen VC MC of the SAS appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.