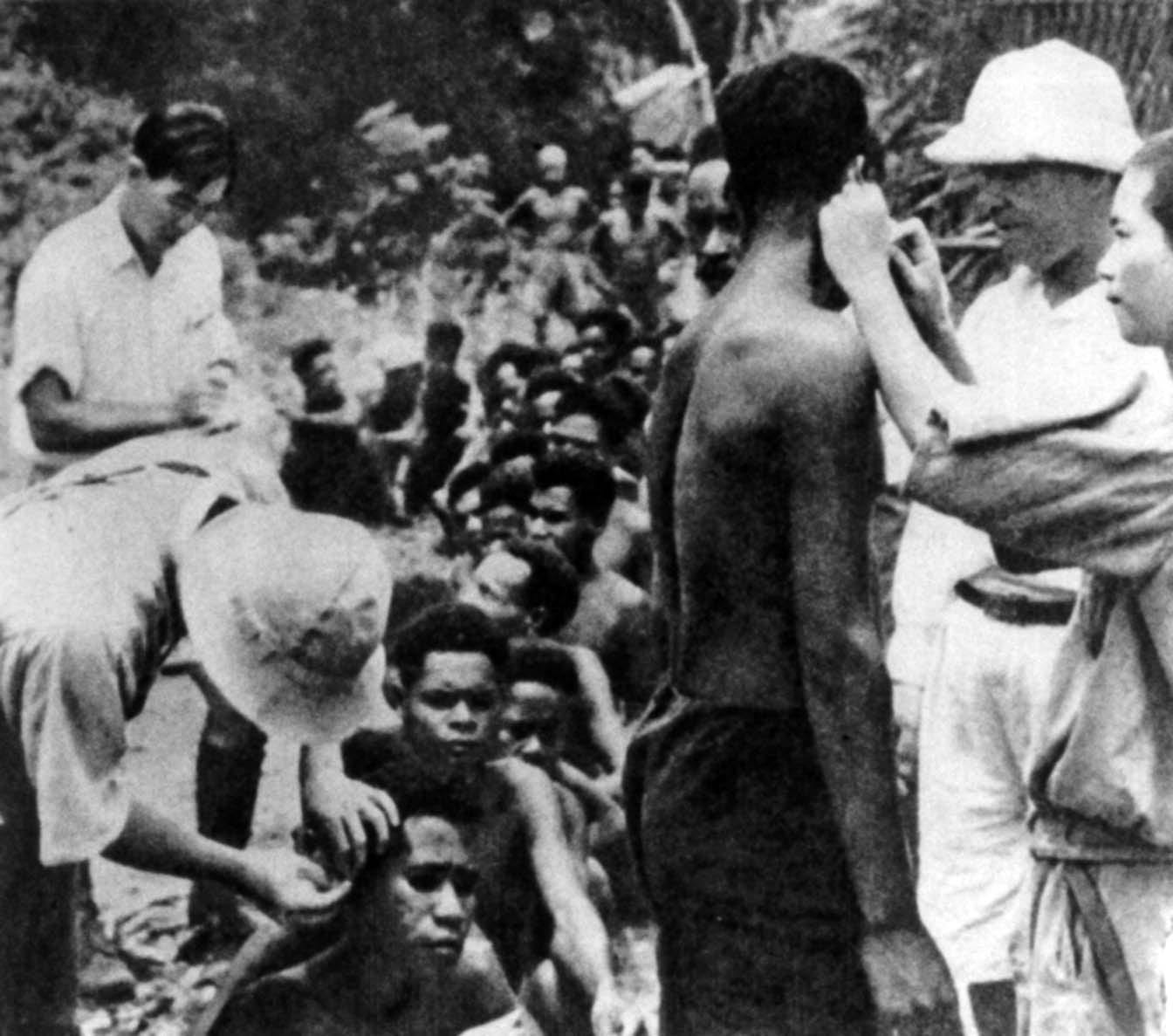

Japanese ambush on New Guinea

7th June 1943: A Japanese officer's recollections of how he travelled deep into the jungle of New Guinea to surprise an Australian position

The struggle to dominate New Guinea continued. Neither the Japanese nor the Allies - principally the Australians and the Americans - had the resources to mount decisive campaigns. The tropical rainforests and the mountainous muddy terrain made military assaults as difficult as anywhere in the Pacific.

The indigenous islanders were dragged into the conflict by both sides. Their loyalties largely depended on where they found themselves when the different armies landed. Before the war, most had had minimal contact with the Australian civil administration, if it existed in their locality at all.

Both sides clung to whatever positional advantages they had, especially the mountain tops and high ground. But with no clear-cut front lines, there were opportunities for infiltration for those who could master the jungle. This brought the islanders into the middle of the conflict.

The following excerpt describes an attack led by a Japanese soldier, Masamichi Kitamoto, on the 7th June 1943:

Part of the way we rode in military police trucks. The objective was to get us as far away from [Lae] before it became light. There were informants among the natives who supplied the enemy with information on our moves. If we met with an ambush along the way then that would be the end of this mission. After leaving the trucks it was continuous marching over unmapped country. We advanced through thick jungle, cutting our way step by step. That evening we arrived at Boana village.

A report came in that there were six Australians at Ofofragen village. Calling Sergeant Sogabe, I drew up plans for battle. ‘We must capture all the enemy alive because I want to get information on their moves.’ The sergeant nodded.

The best way to attack them is after they have gone to sleep. We’ll approach from three sides, fire, then rush their hut. The two squads of infantry under Sogabe, with two light machine guns, would cover their flank and rear, thus cutting off their route of escape. I was to lead the engineers of the Independent 30th Regiment in a frontal attack.

Rabo was sent out as a scout, to inform the village people to run away. I did not wish to get these innocent natives involved in a war with which they had nothing to do.

Stifling the noise of our footsteps, we gradually closed the net around the enemy. Rabo had taught me how to walk without making any noise. The hut of the enemy came in sight. The light was out. It was reported that they were drinking heavily until late, so they must be fast asleep. The enemy was completely trapped.

I ordered the men to fire several shots in the air. The three light machine guns spat fire from three directions. Inside the hut an Australian was shouting something.

The bullets of automatic rifles came flying from the hut. The enemy had decided to fight back. It was a miscalculation on my part, for I believed they would surrender without firing a shot. The enemy fired at random in all directions, while we concentrated our fire on the hut. The outcome was obvious. After twenty minutes shooting, I ordered the men to cease fire.

Inside the hut, there were six dead bodies of the enemy lying about, one Australian and five natives. I realised why he fought back. This Australian soldier could not surrender to us and be shamed before his natives. I felt sorry for him. When I thought that he must have a wife and children, I felt a pang of guilt.

I instructed the soldiers to dig a hole and bury the six bodies. As I stood praying by the side of the grave, Rabo looked at me strangely. ‘Captain, why do you pray for those bad fellows? They are bad devils.’ I could not answer him. It was a contradiction to kill a person then pray for him.

On 7 June 1943 Kitamoto killed Warrant Officer Harry Lamb and five native policemen. The 42-year-old Lumb, an ex-miner who knew the area well, was a member of the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit (ANGAU). ANGAU was responsible for organising local labour, carriers and scouts to support the Australian Army.

In this encounter we captured the secret codes and the enemy weapons, food, one donkey and numerous other supplies, besides killing six enemy. The soldiers ate the chocolate and donned the new enemy uniforms. A queer looking bunch we were. Baggy foreign uniforms and soiled Japanese army caps.

The enemy we killed at the village of Ofofragen may have been the ones who escaped from us before, on our first mission. If so, they were born under an unfavourable star, because if it were not for me they would still be alive today.

Especially the Australian soldier would probably be leading a pleasant life with his family. Man’s fate is changed by just a slight incident. The life we lead is easily affected by actions of other people. This is what we call fate. Even as I write this manuscript, the face of that soldier I killed in New Guinea appears clearly on the paper. The pang of guilt pierces my conscience. I would like to meet the family of this soldier and express my deepest sympathy.

There are not nearly so many Japanese accounts of the war available in English as there are from German sources. This new collection by Australian researcher Peter Williams, Japan's Pacific War: Personal Accounts of the Emperor's Warriors, is the product of over a hundred interviews with Japanese veterans.

These are recollections many years after the event, yet they provide many insights into the brutal conditions in which the Japanese troops and airmen found themselves. All seem to have been unquestioningly loyal to Emperor at the time, prepared to fight on while they starved to the point of cannibalism, ready to commit suicide rather than be captured. A glimpse into the past from men who survived merely by chance.

This excerpt from Japan's Pacific War: Personal Accounts of the Emperor's Warriors appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.