'Enemy Sighted'

30th August 1940: The story of 'The World’s First Integrated Air Defence System' - and how the men and women who operated it were put to the test

The story of the Battle of Britain is often told in terms of the men on the frontline, the ‘Few’ and the planes they flew. But the survival of Britain in the summer of 1940 was also due to striking technological advances, especially radar, and an advanced system for making full use of. It was not enough to receive a warning of enemy aircraft approaching the English coast; it was necessary to respond to that threat in a carefully calibrated way. Launching fighters at every incursion into British airspace would have been playing into the hands of the Luftwaffe.

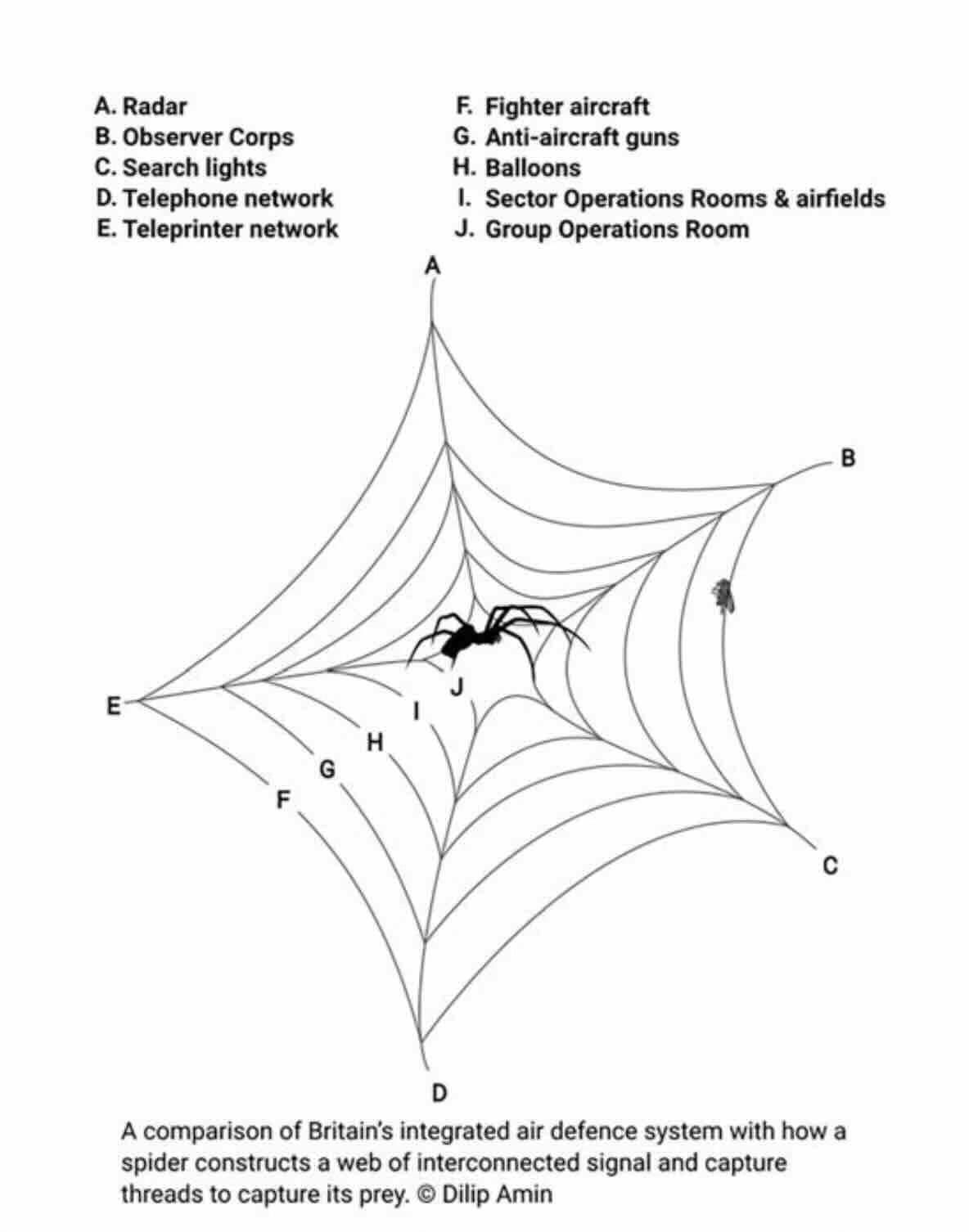

There were other elements of the defence that had to be included in the system, the Anti-Aircraft Guns, the Searchlights, the Barrage Balloons and the whole had to be tied together with a network of communications. All of this was achieved in a remarkable series of developments that were only brought together in early 1940, just before the Battle began.

The story is comprehensively told in: ‘Enemy Sighted - The Story Of The Battle Of Britain Bunker And The World’s First Integrated Air Defence System’ . The following two excerpts look at how the Germans viewed the RAF system and how the men and women operating the system got caught up in the battle on 30th August:

German Understanding of Britain’s Radar Capability

Astonishingly, in October 1938, less than a year before the outbreak of war, the British reciprocated an earlier visit to Germany, and invited the Luftwaffe to reconnoitre the Royal Air Force. The German delegation was led by Field Marshal Erhard Milch, the man responsible for rearming the Luftwaffe. He is reported to have asked, ‘How are you getting on with your experiments in the radio detection of aircraft approaching your shores? [ …] We have known for some time that you are developing a radar system. So are we, and we think we are a jump ahead of you.’ This account is not corroborated by British officers, who were present during the visit, but it does beg two questions: ‘What did the Germans know about British radar?’, and ‘Why was it not taken more seriously by them?’

Regardless of the veracity of what is alleged to have been said by Milch when he visited Britain, it is clear that the vast latticed towers springing up across the eastern and southern coast of Britain had not gone unnoticed. In early 1939, General Martini, the Director of Luftwaffe Signals, despatched Germany’s last airship, Graf Zeppelin II, to investigate the exact nature and capability of the newly erected towers. Germany was also developing radar and would go on to successfully deploy its Freya early warning, and Würzburg anti-aircraft systems against the Allies.

However, there was a crucial difference in the approach adopted by both countries. German radar, operated on a relatively high frequency of around 200 megahertz, while British radar operated on a much lower frequency of around 20 megahertz. As a result, scientists onboard the airship had monitored the wrong frequency, and so failed to detect radio transmissions emanating from the towers. They incorrectly formed the view that British radar was both ineffective and non- operational. Unbeknown to Graf Zeppelin’s crew, the Radar operators who were located beneath the towers had in fact been plotting the track taken by the Zeppelin throughout its surveillance flight, around the eastern edge of England, and up along the coast of Scotland.

General Martini’s Luftwaffe Signals Directorate submitted the inaccurate information on the latticed towers as part of their regular intelligence summaries to the 5th Abteilung. This was the intelligence arm of the Luftwaffe General Staff, responsible for collating information about foreign air forces, and preparing target information for an air war. The intelligence was then forwarded to the German High Command, with the observation that, ‘British air defence is still weak’. Later the same year, the 5th Abteilung prepared a document titled, ‘Proposal for the Conduct of Air Warfare Against Britain’, but there was no mention of British radar. These grave miscalculations were to have catastrophic repercussions for German military ambition during the Battle of Britain.

The French military had showed interest in acquiring Britain’s CH radar, just three months before war was declared. French officers were sent to visit the Filter Room at Bentley Priory, and to attend courses on radar. Arrangements were made for Radar stations to be situated in France, and contrary to British requests, the French shared details on radar with their own manufacturers. In any event, the mercurial speed with which the German military overran France, meant that the project was ended before any work had commenced.

If CH Radar stations had been built on French soil, or if the Germans had coerced French manufacturers into revealing the information their government had perilously shared with them, then Britain’s secret detection capability would have been laid bare before the enemy, and the technical advantage afforded by radar compromised.

Another opportunity to gain some insight into Britain’s radar capability was squandered, when German scientists examined a mobile radar unit, abandoned by the British Expeditionary Force in France, only to dismiss it as being inferior to their own equipment. Arrogance, and a lack of specific intelligence, contributed to a culture of complacency among the German High Command, who underestimated just how vital radar was. This weakness was espoused by the Luftwaffe’s Commander in Chief, Herman Goring, who ‘loathed technicalities of any sort and was totally unable to understand them’.

The culture of complacency and arrogance did not, however, permeate to those leading the Luftwaffe in the air. Adolf Galland, a Luftwaffe Major during the Battle of Britain, understood the significance of Britain’s radar capability:

From the very beginning, the English had an extraordinary advantage, which we could never overcome throughout the entire war: Radar and fighter control. For us, and for our Command, this was a surprise, and a very bitter one. England possessed a closely knit radar network conforming to the highest technical standards of the day, which provided Fighter Command with the most detailed data imaginable. Thus, the British fighter was guided all the way from take-off to his correct position for attack on the German formations. We had nothing of the kind. In the application of radio-location technique the enemy was far in advance of us … For us there was only a frontal attack against the superbly organised defence of the British Isles, conducted with great determination.

There is an old Maltese saying, that ‘to destroy the spider you have to destroy the cobweb’. The inability or unwillingness of Goring and those at the highest echelons of the Luftwaffe to understand the absolute necessity for destroying the ‘web’ that Radar provided, ultimately meant that it remained intact, to be used to lead the defending spider to its prey.

Fortunately for Britain, it had in Dowding the very antithesis of Goring. Fighter Command’s leader proved to be an analytical and apprised opponent, who understood how technology could aid the defence of this country, and so propelled its implementation. Dowding would later state that, ‘the system operated effectively, and it is not too much to say that the warnings which it gave could have been obtained by no other means and constituted a vital factor in the Air Defence of Great Britain.’

‘Enemy Sighted’ also describes how the Air Defence system was put to the test during the Battle of Britain … the following excerpt covers the events at Biggin Hill on 30th August:

This period of the battle is described in an 11 Group report prepared after the war, as having seen ‘much greater intensity and almost exclusively against 11 Group air fields’. One of the worst effected Sector stations was RAF Biggin Hill, guarding the southern approaches to the capital. The ‘Bump’, as it was affectionately known, was attacked on no less than twelve occasions over a five-month period between August and January, underscoring its importance to London’s defence.

On 30 August, the Germans bombed it twice. The morning raid caused damage to the airfield, hindering the ability of its squadrons to take off and land, but it was the second visit that proved to be especially devastating. A relatively small number of Ju 88 bombers inflicted widespread damage across the Sector station, many buildings were destroyed and the supply of gas, electricity and water was cut off. Crucially, the vital telephone lines necessary for essential services across the station to speak with each other, and those required for the Operations Rooms at Biggin Hill and Uxbridge to communicate with each other, were severed.

Section Officer Felicity Hanbury, who had taken cover during the raid, now re-emerged to a scene of absolute devastation. She made her way towards what had moments ago been another WAAF shelter trench to offer support and, as the officer responsible for the 250 WAAFs on the station, coordinate a response in the aftermath of the attack. She could smell gas but, unthinkingly, lit a cigarette to calm her frayed nerves. Jolted by someone shouting, ‘Put that cigarette out before you blow the place to bits!’, Hanbury extinguished her cigarette and continued on her way, passing by the body of a young girl on the ground. The death toll at Biggin Hill on that day would be a staggering thirty-nine people killed.

It is likely that the famous, ‘Put that cigarette out! The mains have gone, can’t you smell gas?’, scene in The Battle of Britain was re-enacted by Susannah York’s character, Section Officer Maggie Harvey, as a tribute to Felicity Hanbury’s actions on this day.

The aerial intruders returned twice on the following day. One of the bombs dropped during the second raid fell just outside the Sector Operations Room, cutting through temporary cables and telephone lines that had been rigged up following the previous day’s raids. All contact across Biggin Hill was lost, but the direct line with 11 Group’s Operations Room was still functioning. The threads forming the spider’s web were still holding, but they were now being severely strained.

WAAF Sergeant Helen Turner, who had remained at the switchboard despite the obvious risk to her safety, was forced to the ground by a colleague just in the nick of time as a 500 lb bomb entered through the roof and exploded, sending deadly shards across the Operations Room. Another WAAF, Corporal Elspeth Henderson, responsible for holding the direct line with Uxbridge open, had also remained at her post. Knocked down by the blast, she was helped to her feet by the Station Commander who had just walked in and was himself cut by flying debris. Picking up, refilling and lighting his pipe, which had been forced from his mouth by the explosion, he congratulated Henderson on her composure. She replied stoically, ‘There wasn’t much else I could do anyway, was there, sir? After all, I joined the WAAFs ’cause I wanted to see a bit of life.’58

A third WAAF telephonist, Sergeant Joan Mortimer, was on duty in the Station Armoury at the time of the raid. She remained at her switchboard, relaying messages to the defence posts around the airfield, even though she was surrounded by several tons of high explosives. The airfield itself was still being bombed when Mortimer ran out with a bundle of red flags to warn returning pilots, by marking where bombs had landed but not exploded. Even when one exploded nearby, knocking her off her feet, she got up and carried on.

The actions of Hanbury, Turner, Henderson and Mortimer showed beyond doubt that those who had warned against employing women in such highly pressurised environments had been utterly wrong. Hanbury was awarded the first Military MBE for ‘setting a magnificent example of courage and devotion to duty during heavy bombing’. Turner, Henderson and Mortimer were each awarded the Military Medal, for their courage, their cool, calm, collected conduct, and the example they set to others that day.

The Luftwaffe was putting Fighter Command under severe pressure and while it can be said that the defending forces were fighting for their survival, it is also clear that the aggressors had so far failed to achieve their objective, the destruction of Fighter Command in the south of England within four days and were failing in their objective of eliminating the Royal Air Force within four weeks.

© Dilip Amin 2023 ‘Enemy Sighted - The Story Of The Battle Of Britain Bunker And The World’s First Integrated Air Defence System’ . Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd. NB Not all of the above images are reproduced in this book.