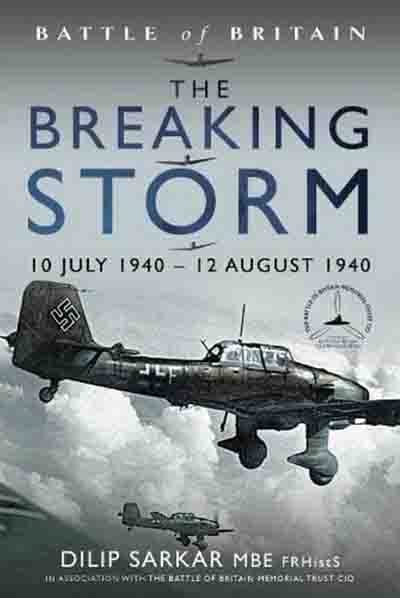

'The Breaking Storm'

2nd August 1940: The Luftwaffe plan 'Adlerangriff' - an excerpt from Dilip Sarkar’s seven-volume history of The Battle of Britain:

Dilip Sarkar has immersed himself in the history of the Battle of Britain and has published several titles examining different aspects of the campaign over the years. A few weeks ago, I featured ‘Spitfire! - The Full Story of a Unique Battle of Britain Fighter Squadron'. More recently Sarkar turned his attention to writing the ‘big picture’ - a full history of the battle. The result was his seven-volume history of The Battle of Britain, first published in 2023. This is a terrific accomplishment, bringing together many personal stories from airmen and other participants, alongside a thorough explanation of the context, as well as a day-by-day account of the various dogfights and other action.

The following collection of excerpts from The Breaking Storm: 10 July 1940 – 12 August 1940 (Battle of Britain) is illustrative of Sarkar’s approach, covering just one day in the battle. Here he tells the story of the German thinking behind their campaign at this stage, personal stories, the ongoing technical developments of the aircraft, as well as some of the neglected participants in the battle - the merchant seamen of different nationalities, so many of whom were victims of the German bombing of convoys.

FRIDAY, 2 AUGUST 1940

On this day, the OKL [Luftwaffe High Command] circulated a directive based upon the previous day’s Hague conference, outlining the thirteen-day aerial campaign against Britain. The objective of this so-called Adlerangriff (Eagle Attack) was clear: the destruction of the RAF.

The plan called for Luftflotten 2 and 3 to launch the attack with three successive raids on a scale hitherto unseen. Then, the following day, Luftflotte 5 would attack from Norway. It was anticipated that to reduce Fighter Command to less than 300 aircraft would take just four days.

In 1921, the Italian General Giulio Douhet had published The Command of the Air, in which he theorised that in future ‘The disintegration of nations … will be accomplished directly … by aerial forces.’ Many dismissed his writings as absurd – but Göring and other German air force officers took note. During the Spanish Civil War, at Guernica the Luftwaffe had provided a terrifying and early example of the destruction air power was capable of, following this up with similarly violent aerial bombardments of Warsaw and Rotterdam in 1940.

Douhet had advanced the strategy of aerial bombing delivering a ‘knockout blow’, neutralising the enemy’s war industry and relentlessly attacking civilian populations in order to cause panic, destroy morale and even cause uprisings against their own governments which had failed to protect them. Future events would prove Douhet wrong, because civilian populations under fire would prove stoic, but his theories found a disciple in Göring, who, Oberst Werner Kriepe, a former bomber commander, now a staff officer, recalled was ‘entranced’ by the Italian’s theories.

Consequently, Göring now believed that his Luftwaffe alone could defeat Britain – and was eager to set about the task. Setting aside the inescapable fact that Douhet’s was a flawed doctrine, the problem was that the Luftwaffe had been created not as a strategic air force equipped with heavy bombers (ironically Göring had cancelled the four-engine bomber programme in 1937), but essentially as flying artillery intended to support the army with light and medium bombers. Göring was now, therefore, preparing for a campaign his Luftwaffe was actually ill-equipped to effect.

Supporting the army in assault river crossings was one thing, but a seaborne invasion, taking aside the Luftwaffe’s inadequacy to mount a strategic bombing campaign, was quite another: the Channel was too wide, meaning that the Me 109, like the Hurricane and Spitfire designed and intended as a short-range defensive interceptor, would continue to operate at the extremity of its range, providing little fuel for combat over south-east England, and the twin-engine Me 110 – in which Göring put great store – although enjoying greater range had already proved no match for the RAF’s single-engine fighters.

Going forward, the Luftwaffe Chief of Staff, Generalmajor Hans Jeschonnek, approved a plan by Oberst Paul Deichmann, Chief of Staff to General Bruno Loerzer’s Fliegerkorps II to destroy Fighter Command in the air. To date, in spite of Oberst Fink’s success in denying the RN Dover as a base, defence of the Channel convoys had not enticed Fighter Command to battle en masse.

Deichmann, who had served in the RLM as a staff officer since 1934 and had never flown in combat, firmly believed that only one target would force the RAF fighters off the ground in great numbers: London. Hitler, however, still cautious of Britain, refused to permit this, repeating: ‘I reserve the decision on terror attacks to myself’. So far, not even Bomber Command’s nightly raids on Germany had made Hitler unleash ‘annihilating reprisals’. So attacks on London were forbidden, and instead other means had to be found with which to bring Fighter Command to battle.

Consequently, it was decided that the primary focus of the Adlerangriff, scheduled to begin on 10 August 1940, was airfields known or believed to be used by Fighter Command – and here again is revealed another Luftwaffe deficiency: the failure of air intelligence. It was clear that Oberst ‘Beppo’ Schmid failed to appreciate how Fighter Command was organised, deployed and controlled, this leading to his inaccurate Studie Blau, which informed the OKL, erroneously, as to these crucial subjects.

...

At this time, Fighter Command comprised fifty-eight squadrons, of which twenty-nine were Hurricane-equipped, but only seventeen had the superior Spitfire.

Of these, three Hurricane and four Spitfire squadrons were based in 10 Group, and twelve Hurricane squadrons and just five with Spitfires in 11 Group – and it would be in the skies over southern England that this battle would be decided.

Additionally, there were seven squadrons of Blenheims, two of Defiants, and even one Fleet Air Arm Fulmar squadron and another flying obsolete Gladiator biplanes.

In truth, and without in any way marginalising the courage and contribution of aircrew operating these other types, it was the single-engine Hurricanes and Spitfires that really mattered – and there were, excluding reserves, just 288 of both types in 10 Group and 11 Group – facing the 2,000 fighters and bombers of Luftflotten 2 and 3.

Although at the Hague conference Oberst Osterkamp had been ‘bitterly disappointed’ with having been allocated some 700 Me 109s and 229 Me 110s, his single-engine fighter force alone outnumbered 10 Group’s and 11 Group’s Hurricanes and Spitfires by over 3:1. No.12 Group, which could be called upon to both defend 11 Group’s airfields while Air Vice-Marshal Park’s fighters were engaged further forward and reinforce the south-east if necessary, comprised of three Hurricane squadrons and four of Spitfires, another eighty- four fighters, but essentially the brunt of this coming battle would be borne by 11 Group. It was not just numbers that were important, however: performance was too.

The Germans had tested and compared captured Allied aircraft at E-Stelle Reclin, where Major Werner ‘Vati’ Mölders flew and evaluated three of the enemy aircraft types he had been shooting down:

It was very interesting to carry out the flight trials at Rechlin with the Spitfire and Hurricane. Both types are very simple to fly compared to our aircraft, and childishly easy to take-off and land. The Hurricane is good natured and turns well, but its performance is decidedly inferior to that of the Me 109. It has strong stick forces and is ‘lazy’ on the ailerons.

The Spitfire is one class better. It handles well, is light on the controls, faultless in the turn and has a performance approaching that of the Me 109. As a fighting aircraft, however, it is miserable. A sudden push on the stick will cause the engine to cut, and because the propeller has only two pitch settings (take-off and cruise), in a rapidly changing air combat situation the engine is either over-speeding or else is not being used to the full.

...

‘The Beaver’ [Lord Beaverbrook - Minister of Aircraft Production] gave control of the Castle Bromwich Aeroplane Factory (CBAF) to the aircraft manufacturer Vickers, and things began moving immediately. Experienced workers were brought to Birmingham from Supermarine at Southampton, and the more complex components were produced at Southampton. In June 1940, Beaverbrook’s target of just ten Spitfires was miraculously achieved; twenty-three followed in July, thirty-seven in August and fifty-six during September.

The important thing is that all of these Spitfires now being produced by the CBAF were new Mk IIs. This enjoyed several benefits over the Mk IA currently in operational service and it was naturally important to expedite production and delivery to the squadrons. The Spitfire Mk II was powered by the Merlin XII, which produced 1,175 hp, as opposed to the Mk IA’s Merlin III’s 1,030 hp. The Mk II’s top speed was 370–15 mph faster than the Mk IA. The new Spitfire’s rate of climb was 2,600ft a minute, 473ft a minute more than the Mk IA. The new engine was fitted with a Coffman automatic starter, which reduced starting time, and, most importantly, all of the new Spitfires were fitted with the Rotol CS propeller as standard. The first Mk IIA was delivered to 611 Squadron at Digby on 22 July 1940, and as the battle progressed, numbers would increase.

...

On 2 August 1940, Squadron Leader Ronald ‘Boozy’ Kellett, at Northolt, formed and was in command of 303 (Polish) Squadron – which at first existed in name only. That Kellett spoke French fluently, had experience of forming squadrons and converting pilots to the new monoplane fighters, doubtless explained his selection for this role.

Squadron Leader Kellett:

The day in August came when a body of men wearing dark blue battledress and berets arrived, with strange words of command and an unusual facial appearance. They were soon sorted out into flights ‘A’ and ‘B’, and ‘C’ for maintenance, and bit by bit order appeared out of chaos. We officers met in the Mess and we learnt something of the battle of and their escape from Poland to France, and arrival in England. They mostly spoke French, which enabled me to communicate reasonably freely with them.

To overcome the language difficulty and procedural differences, a system of ‘double-banking’ was adopted in these squadrons; RAF officers were in charge, but their roles were duplicated by Polish officers, who shadowed their English- speaking counterparts. No. 303 Squadron – named after Kosciusko, a Polish national hero who had been General Washington’s adjutant in the American War of Independence, and later a national leader – was formed from two Warsaw-based PAF squadrons, which were smaller than RAF squadrons. Consequently, the Polish 111 became ‘A’ Flight, and 112 ‘B’.

The Polish officer duplicating Kellett’s role was Squadron Leader Zdzislaw Krasnodebski, while the Canadian John Kent, commanding ‘A’ Flight, was shadowed first by Flight Lieutenant Henneberg, then Flight Lieutenant Urbanowicz, and in ‘B’ Flight, Flight Lieutenant Athol Forbes’ Polish counterpart was Flight Lieutenant Lapkowski. Like Kellett, Forbes also had good French, while Kent’s was poor, so the ‘A’ Flight commander took to learning Polish, which was much appreciated by his Polish subordinates.

In August 1940, certain of 303 Squadron’s pilots were sent to RAF Uxbridge on an R/T course, and for others English lessons began. Today, it is difficult to imagine how primitive some things were just over eighty years ago.

Sergeant Reg Nutter, a Hurricane pilot of 257 Squadron, also attended that R/T course and recalled that:

This proved to be quite interesting as it had a two-fold purpose – to train pilots in R/T procedures and to train the controllers who would later control us from Operations Rooms. Marked out on the playing fields was a large map of the British Isles and a part of Western Europe. We pilots were given tricycles, which had formerly been used to sell ice cream!

In the box at the front was a TR9 radio, which, at the time, was standard aircraft equipment. We wore headphones and were surrounded by a set of blinker-like boards, which restricted our vision. The driving chain and sprockets were arranged in such a way that when we pedalled twenty-five times the wheel moved round just once! Thus our speed across the maps matched the speed of fighter aircraft across the ground at normal throttle settings.

Down in the stadium a complete Operations Room had been built. This was fully manned by trainee Controllers, WAAF Plotters etc. On top of the stadium was a spotter who passed our position, and the position of the person designated as the ‘enemy’, down to the Operations Room. The ‘Controllers’ could then vector us by radio to make interceptions. We both learned a lot from the course but found it somewhat difficult to sit down on our final return to the squadron. Pedalling around in the hot sun in a serge uniform made one quite sore in a certain part of one’s anatomy!

At Northolt, work was ongoing to convert the Poles to the Hurricane. Many of the Poles were experienced pilots, and had even seen combat – but although some had flown obsolete French monoplanes, none had flown modern RAF fighters. That said, both of Squadron Leader Kellett’s English-speaking flight commanders had only just converted themselves to the Spitfire and Hurricane, and, along with their CO, experienced a pilot though he was, neither had yet been in combat.

So, as with other many other squadrons at the time, everyone was learning. In addition to the language barrier, the Polish pilots faced another difficulty, in that the controls of British aircraft were contrary to Polish machines. For example, in Polish aircraft the throttle was pulled back to accelerate, whereas in British designs power was increased by pushing the throttle forward. All of this took time to overcome, but did nothing to mollify the Poles’ frustration at being unable, as yet, to fight Germans. Nonetheless, after the Poles were first checked out in the Link Trainer simulator, training continued apace, on the ground and in the air.

Squadron Leader Kellett commented that ‘Converting the Poles to Hurricanes was going well, apart from one or two landings with the undercarriage up.’ This, however, was far from uncommon when pilots were changing over from flying biplanes with fixed undercarriage; the 303 Squadron British CO continues:

We had all learned certain Polish words: ‘Klapy’ = flaps [which biplanes did not have), and ‘potwozie’ = undercarriage, so in the air we could remind the pilots of these needs. The rumour circulated that the Poles were so keen to land that they failed to put the undercarriage down – typical schoolboy humour imparted to high places. I would have none of this, as they were very quickly being converted to Hurricanes and had retractable undercarriage for the first time.

There was an incident that illustrated the problem of language and non-communication. A principal of the dispersal of aircraft was no aircraft should be nearer than, say, twenty yards from the next, and on seeing two aircraft wing tip to wing tip, I ordered a Polish airman to start one so that it could be taxied to another place.

There was a certain amount of gesticulating which I ignored. I should have noticed that the air pressure for the brakes was nil, but once the aircraft was started I taxied onto the slope of the taxi-track. I tried the brakes to turn the aircraft but they didn’t work – and within seconds the eight-ton aircraft had crashed into one of the dispersal huts, destroying its propeller and not improving the hut either! As chance would have it, the Command Accident Officer was just walking to dispersal and witnessed the event. He told me not to report the accident, saying there were too many to deal with and that he quite understood the reason.

During the training period I had, with the agreement of General Ujesjski, recruited more pilots from the Polish collecting depot at Blackpool and I think we had about thirty-two operational pilots in the squadron. It was therefore possible for each pilot to be on duty twenty-four hours on and twenty-four off.

We changed over at one o’clock. No pilot on duty was allowed to leave the Mess, early bed and early rising, the squadron being on readiness from half an hour before sunrise until half an hour after sunset. We suggested to the ground crews that they should do the same but British and Polish NCOs replied that while our pilots were in the air they wanted to remain on duty, and so it was. I don’t believe any Squadron had better NCOs or aircraft maintenance than 303.

...

Friday, 2 August 1940 was a day of rain and cloud over southern England, making for reduced enemy air activity. No.19 Squadron’s Flight Lieutenant Clouston, up from Duxford’s satellite airfield at Fowlmere, to which the squadron had been dispersed, with Pilot Officer Burgoyne and Pilot Officer Aeberhardt, intercepted a He 111 off Cromer Knoll, at 11.15 hrs, while patrolling a convoy. Each member of Blue Section fired at the bomber. The ORB states:

Flight Lieutenant Clouston, who was in an eight-gun aircraft, disabled the starboard engine and possibly killed the rear-gunner. The machine carried out evasive tactics, making full-use of 9/10ths stratus cloud at 1,500ft, escaped eastwards.

The other two Spitfire pilots were flying the still troublesome cannon-armed Mk IB, which were already notorious for jamming at the worst possible moment and would cause 19 Squadron considerable angst in the coming weeks. This He 111 was claimed as damaged and represented 19 Squadron’s first action of the Battle of Britain.

...

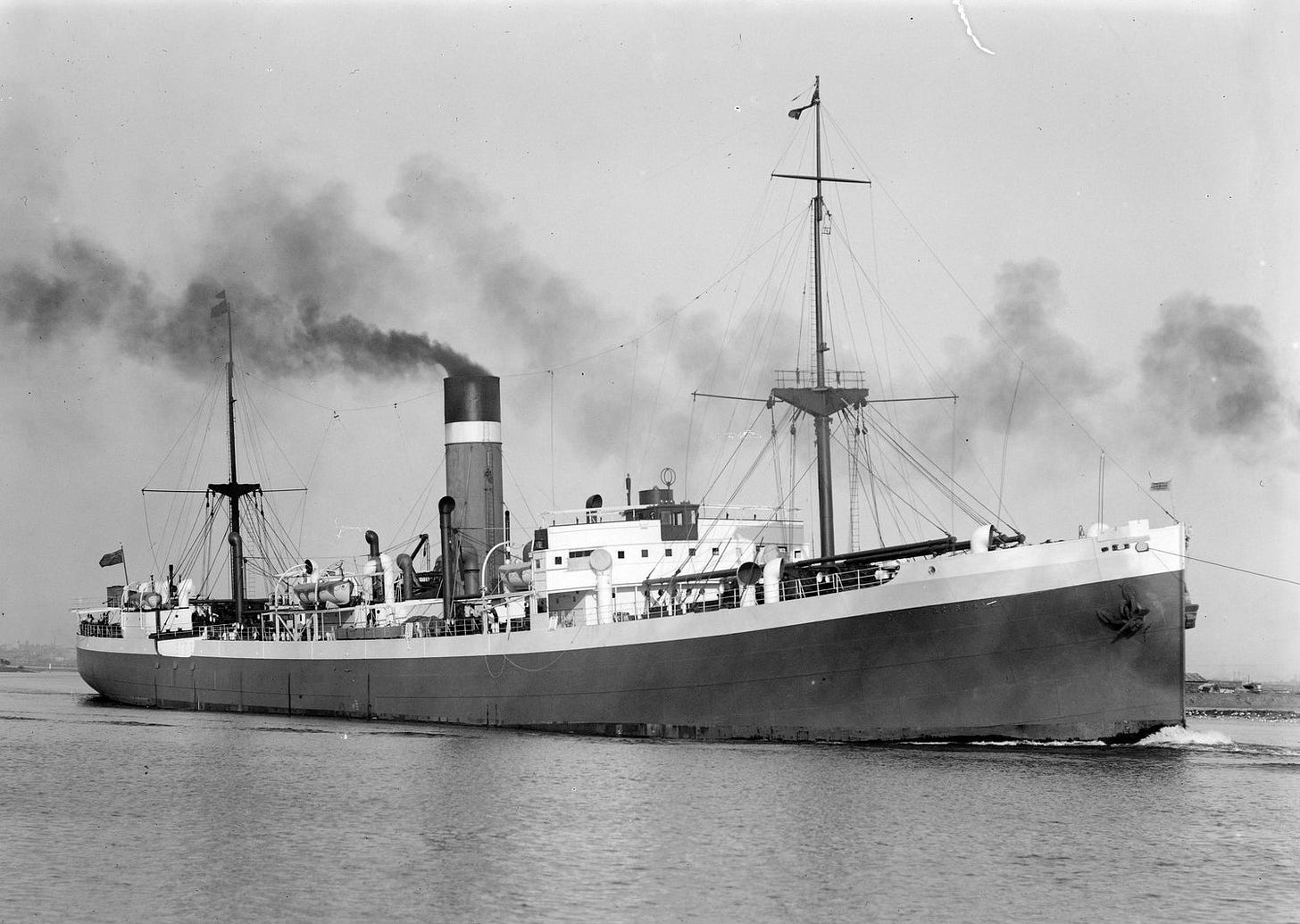

On this day, the Ellerman Line-owned and Liverpool-registered British merchantman SS City of Brisbane was bound for London from Port Pirie, Australia, carrying lead, flour, tinned fruit and other foodstuffs, when the ship was attacked and badly damaged by German bombers. Beached on the southern end of Long Sand in the Thames Estuary, the battered hulk burned for three days before breaking in half and sinking.

Eight Indian sailors were killed, all of whom remain missing and are remembered on the Chittagong Memorial, commemorating the 400 sailors of the Indian Navy and 6,000 of the Indian Merchant Navy lost at sea during the Second World War. One man, fatally wounded, was brought ashore, but died on 11 August 1940. Indeed, between 2 July and 8 August 1940 inclusive, at least 227 merchant seamen lost their lives in the English Channel, the youngest being several 16-year- olds; the oldest was aged 66.

What is surprising, however, is that many were not British. For example, ten sailors lost with the SS Aeneas on 2 July 1940 were from Hong Kong. Indians, like those lost on SS City of Brisbane, however, made up the largest number of non-British personnel, either serving with seagoing lines or the Indian Merchant Navy.

On 29 July 1940, for example, of the thirteen men killed when the SS Clan Monroe went down, twelve were Indians. Interestingly, all of these Indian sailors who lost their lives aboard these two ships appear to have been Muslims from pre-partitioned India, the jewel in Britain’s Empire.

Although no figures are available for 1940, in his article ‘Merchant Seamen During the War’, which was published in 1946, Sir William Elderton stated that in 1938 there were 192,375 men employed on British merchant ships, of whom only 131,885 were British; the others were foreigners, 9,790 mainly Europeans, and 50,700 Indians and Chinese. By 1938, 27 per cent of seamen engaged on foreign voyages were Chinese or Indian, with a further 5 per cent including Arabs, West Africans and West Indians domiciled in British ports. It was these men who crewed the ‘Coal Scuttle Brigade’ and merchant ships bringing essential supplies to the besieged island in summer 1940 – a rarely acknowledged fact.

© Dilip Sarkar 2023, 'The Breaking Storm: 10 July 1940 – 12 August 1940 (Battle of Britain) . Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd. NB The above images are not from this volume.