Stuka pilot over Dunkirk

1st June 1940: A dramatic account of one day's fighting from 'Memoirs of a Stuka Pilot'

A mixture of luck, defiance and German hesitancy saved the men of the British Expeditionary Force who escaped from the beaches of Dunkirk. The counter-attack at Arras gave the German High Command pause for thought, as they became nervous about the panzers thrusting so far ahead of the rest of the Army. Hitler had eventually ordered a halt to the panzers on 24th May, giving the BEF a vital two-day window to establish a defended perimeter around Dunkirk. He was also influenced by Goering, who promised him that the Luftwaffe could be left to finish off the British forces.

Within the Luftwaffe, the role of the dive bomber had suddenly gained new prominence, introducing a novel approach to air tactics, attacking in close support of the ground forces.

Helmut Mahlke had joined the German Navy as a cadet in 1932. He served as an observer in a float plane before being transferred to the Luftwaffe, where he continued to serve as an observer on the Ju 87 ‘Stuka’ dive-bomber. He was therefore relatively senior in experience when he eventually trained as a pilot on the Stuka in 1939. It was as a Staffelkapitan - Squadron commander - that he led three attacks on Dunkirk shipping on 1st June 1940, one of several episodes described in detail in Memoirs of a Stuka Pilot:

By this time the British were sending every vessel - naval, merchant or civilian, which was capable of carrying troops - across the Channel in a desperate attempt to evacuate their expeditionary corps from Dunkirk. And on this particular day, 1 June, we had been ordered to attack this shipping off Dunkirk’s beaches.

We approached the target zone above a thin layer of cloud. In the harbour of Dunkirk itself a number of ships were lying half-submerged on the bottom. Our previous attack on the lock gates appeared to have been successful. Along the beaches the British had driven long lines of vehicles into the water, presumably to act as makeshift boarding stages. Standing close inshore there was a mass of shipping of every conceivable kind.

From our height it was difficult to make out which of the vessels had already been hit and which were still seaworthy. The Luftwaffe was up in force, with formations of aircraft attacking in waves one after the other. There was a tremendous amount of activity in the air from both friend and foe alike. But our fighters seemed to be keeping the other side in check.

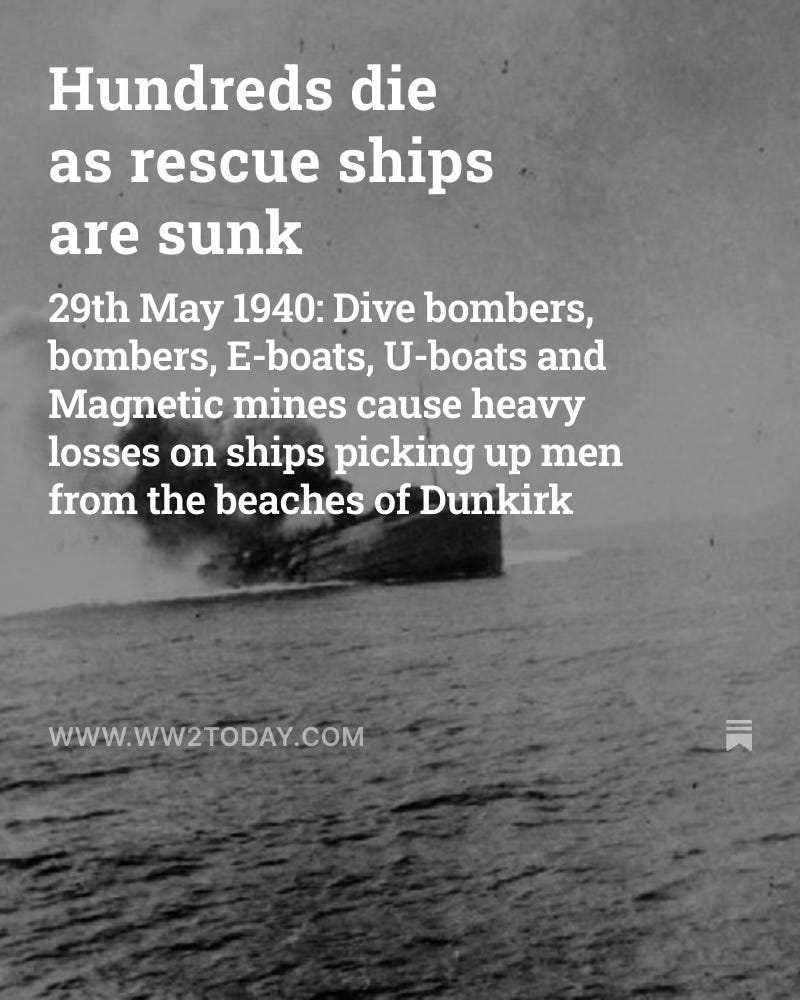

We arrived over the target area unmolested and split up into smaller formations to carry out our attacks. I led my Staffel down against a fair-sized steamer that was getting under way just offshore. We scored several hits amidships and near the stern of the vessel. There were some heavy bursts of Flak to port, but as we couldn’t hear the crump of the exploding shells, they were clearly too far off to be of any danger. Then more Flak to starboard. This time it was pearls of little red ‘mice’ chasing each other through the air, indicating tracer fire from light or medium weapons. We hurriedly jinked away - turning sometimes gently, sometimes sharply - until we were safely out of range.

As we flew back to base I couldn’t get the horrific spectacle that was Dunkirk out of my mind. An absolute inferno I Those poor beggars down there desperately fighting for survival. Just as well that at our height we were spared the gory details. True, the enemy was also doing his utmost to shoot us down. Just how much lead had been aimed my way again today I dreaded to think. But those men down there, trying to escape but packed together so tightly on board their ships that they could hardly move, didn’t stand a chance if set upon by Stukas.

Why didn’t they lay down their arms? They’d lost this battle. There could be no argument about that But I had to put such thoughts out of my mind. We were at war, and as soldiers we had to carry out our orders. And that we had done. In fact, we were more than a little proud to have performed our duty in the way expected of us. So it was best not to dwell too much on the drama being played out below.

After nearly two hours in the air we all, without exception, landed safely back at Guise. Two hours later, however, and we were taking to the air again. Same situation, same orders. Over the target area we saw the ship that we had attacked earlier lying dead in the water, listing badly and with its stern under the surface. For this present mission we had split up into separate Ketten and were searching for fresh targets a little further out to sea.

Through the thin layer of cloud the shape of a larger ship came into view ahead of us. We started to dive. But as we broke through the cloud layer I could see that the vessel had already been hit and was partly under water. Pull out of the dive - quickly look for a new target. Not far away a small transport of scarcely 2,000 tons was fleeing northwestwards at top speed. It wasn’t long before I had it in my bombsight. We were already at a fairly low altitude, but with just enough height left to carry out an attack. Release bomb - recover - observe results: I had missed completely, but my wingmen more than made up for it with two direct hits on the vessel's afterdeck. The ship’s sternpost disappeared beneath the waves as it slowly began to sink.

‘Spitfires coming in from starboard astern,’ Fritzchen Baudisch calmly reported. Get her round! Banking steeply we turned to meet the enemy. Let battle commence! This time, fortunately, only a handful of Spitfires had managed to penetrate our fighter screen and get close enough to attack us. Twisting and turning, we somehow succeeded in fending them off. There were several very nasty moments, of course, but after a fraught ten minutes, we were finally able to make a break for it and retire almost unscathed. We re-formed and returned to base in close formation - mission accomplished.

Another two hours and we were taking off again and heading for Dunkirk and the British evacuation shipping for a third time. Close inshore, all we could see were stranded and half-sunken vessels and floating wreckage. Further out to sea, about 10km from the coast, there was still a whole flotilla of little ships of every kind: coastal steamers, sailing boats, tugs towing barges, and much more. There were also one or two bigger ships amongst the throng.

The leading Ketten were already selecting their targets. We spotted a tug struggling northwards with a large lighter in tow and I gave the signal to attack. As we dived through the thin but persistent layer of cloud Baudisch reported: ‘Kette to port already diving on same target!’ I levelled out and decided to look elsewhere. Not far away I caught sight of a ship that had been hidden by cloud up until that moment. It was by no means huge - perhaps 1,000 to 2,000 tons - but big enough. So a quick change of target to starboard. Put her nose down - attack! Because of the abortive dive on the tug we were already below 500 metres, but I went even lower. Closer - now! My bomb hit the water immediately ahead of the ship’s bow.

As we started to climb away we kept our eyes glued to the vessel. Unable to take avoiding action in time, it was steaming straight through the widening circle of ripples that marked the point where the bomb had disappeared into the water. At that moment there was an almighty explosion immediately under the middle of the ship. It seemed to lift right out of the water and bits of wreckage were hurled a good fifty metres into the air. A fascinating sight - but a horrible one!

‘Fighter to port!’ Baudisch’s voice sounded in my earphones. He loosed off a few rounds - but then his gun jammed. The Spitfire was curving in for a stern attack. I reefed my machine around in an effort to meet it. But the distance between us was far too small. Both still banking almost vertically, we flashed past each other no more than twenty metres apart. He turned in for another attack.Again I dragged the Ju 87 around onto a collision course. And again we shot past each other with only metres to spare.

'Fighter on the right!’ A second Spitfire was closing in fast from the other side and already getting dangerously close. No time to turn in towards this one. He’s going to open fire at any moment now. I hauled back hard and sharp on the stick and the fine white strands of his machine-gun fire passed beneath us. One of the Spitfires was coming in from astern again. Another steep 180-degree turn to meet this new threat. The enemy fighters made several more passes, but each time I was able to face them almost head-on. I didn't manage to get in a single shot at them, but my aggressive tactics were enough to put them off their aim as well.

A Spitfire raced past me one last time before they finally broke away. They must have been running short of fuel and needed to get home. Then I noticed that one of the pair had curved in on my tail again and was slowly drawing level with me off to my right. He was presumably out of ammunition, for he showed no evil intent. He must also have realized that he had nothing to fear from Fritzchen in the rear cockpit, who was still struggling desperately to clear his stoppage. When we were almost wingtip-to-wingtip, he looked across at us and raised his hand to his flying helmet in salute! Dumbfounded, I automatically returned the compliment. Then he banked away in a graceful arc and was quickly lost to sight.

We were alone again - and out of danger. Throttling back to economical cruising speed, I gave my hard-worked engine a breather as we set off to follow our comrades back to base. But I could not get that salute - given by a tough opponent at the end of a hard fight - out of my mind. It had almost been like a medieval knight raising his visor before leaving the field after an undecided jousting contest. Were we the modern knights of the air? That was undoubtedly overdoing things, far too naive and romantic a notion. But what would flying be without a touch of romanticism? That such a gesture was still possible — despite the severity of the air fighting, and despite the heavy losses on both sides - was surely evidence enough that there was such a thing as the brotherhood of the air.

It had made me realize that those of us who shared the freedom of the skies, although having to do our duty on opposing sides in times of war, were nonetheless joined by a common bond. How many soldiers fighting on the ground, I wondered, would be granted an opportunity of this kind to demonstrate their respect for a valiant opponent? And how many would have the wit to seize that opportunity should it arise? Not many, I’ll wager. And so I mentally doff my hat! That unknown British pilot was a remarkable man. (Although I never did discover his identity, he still has my total respect to this day.

In the meantime, however, the realities of the moment had reclaimed my attention. Our right wing had taken a few hits and a thin stream of some fluid or other was escaping from the trailing edge. Fuel? The fuel contents gauge was showing normal. So was the oil pressure gauge. Probably just some minor damage to one of the less important oil lines. It was now that Baudisch told me: ‘One of those fighters was only firing with his four starboard machine guns.’ ‘We’ve had the devil’s own luck again then, Fritzchen. It could have been very nasty for us if all his guns had been working! But make sure you’re tightly strapped in when we land. That burst that went under us was a bit too close for my liking. Our tyres may have caught a packet.’

...

There had been so much going on in the skies above Dunkirk - and on the land and water below - that it was more than one pair of eyes could possibly take in. We could count ourselves lucky that we had at least been aware of the most important parts of the confused battle, those that directly affected us, and had always been able to react accordingly. But the overall picture of the sprawling drama that was Dunkirk - the innumerable separate combats, the personal tragedies, the individual fates that were being decided during every single minute of this momentous day - was simply too huge to grasp.

© Frontline Books 2013 and 2019, 'Memoirs of a Stuka Pilot'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.