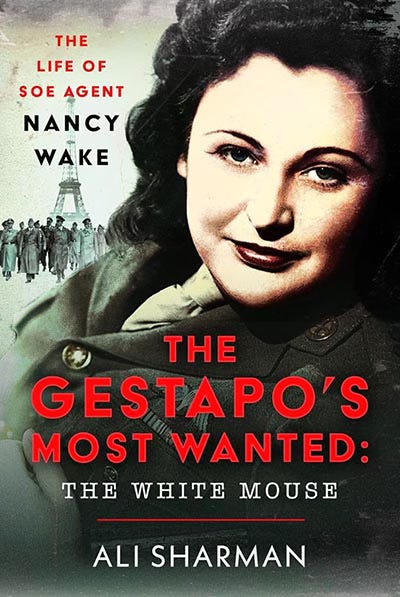

'The Gestapo's Most Wanted'

A new biography of 'The White Mouse' - the indomitable Nancy Wake, who helped Allied aircrew escape from occupied France and then led a Resistance Group

The young Nancy Wake, born in New Zealand and brought up in Australia, had already led an exceptional life before the war broke out. Running away from home as a teenager, she eventually found herself in the southern French port of Marseille, where she married her industrialist husband, Henri Fiocca. They were well placed to live a quiet life and wait out the war years - but instead chose to throw themselves into resisting the French occupation. By her nature, a free spirit and described by many as ‘a force of nature’, Wake distinguished herself as a courier for the Resistance.

Wake used her femininity to outfox the Germans for many months, but eventually they realised they were dealing with an exceptional character. As a prominent woman in the Resistance, she was suddenly a target. The newly published The Gestapo’s Most Wanted - The White Mouse: The Life of SOE Agent Nancy Wake tells the story of how this was just the first part of her resistance career. She would escape to England only to be trained in the SOE and then parachute back into France:

Nancy had had no intention of leaving France in 1943, despite the increased risks to members of the Resistance. But by the autumn, her time in Marseille was forced to come to an end.

O’Leary arrived at the Fioccas’ apartment one evening, clutching a piece of paper in his hand. He asked Nancy, with uncharacteristic seriousness, to take a seat in the salon. Then he showed her what he had been holding. It was a ‘wanted’ poster, and it described a female Resistance agent who had been nicknamed La Souris Blanche: The White Mouse. Beneath the name was a bounty for five million francs being offered for her capture. It was clearly intended for distribution amongst both French and German officials. Nancy’s German was only rudimentary, so she had to wait for O’Leary to translate the rest of the information that it revealed.

‘We’ve been hearing rumours of this for a while,’ he said. ‘Both here and in Paris the Gestapo have become aware of a female agent. In short, they know that there is a woman working for us in the south, although they do not know exactly who she is.’

The missive reported other details that revealed a lack of real information that could help them identify the agent. She was described as being beautiful but blonde, for one thing. Yet at the heart of the matter, the Gestapo were, of course, correct about a key fact – they had begun to realize that, just as Nancy had told the others at the beginning of her involvement with the Resistance, women could get away with a whole lot more than men.

The Gestapo’s eyes had therefore started to turn in that direction, once they had begun to understand just how successful the Resistance had been in waging its secret war right under their noses. But too many individuals had been busy racing to unmask this particular agent and claim the generous bounty, so there had been little collaboration between the different branches of the Gestapo and the Vichy authorities until then, ensuring that only slow progress had been made towards her identification.

‘But make no mistake, this is you, Nancy,’ O’Leary continued, ‘even if they don’t have your name yet. The information might be conflicting from different sources, but they’ve known about a female agent for a while, and the latest reports that we’ve managed to get hold of make us think that they’re closing in on identifying you at last.’

‘The White Mouse,’ Nancy repeated slowly. ‘Not very flattering, is it, to be compared to such a small and troublesome creature?’ Despite Nancy’s derision of the nickname, however, it did infer her ability to resist capture, suggesting that she was as elusive as a mouse and able to deftly slip through the grasp of the Gestapo.

The colour probably emphasized her rarity, suggesting that she was a particularly clever or cunning creature. O’Leary smiled. ‘Perhaps it rather belies their fear of you, seeing as this poster tells us that you are, right now, at the top of the Gestapo’s ‘Most Wanted’ list in Vichy.’ Nancy gave a bitter laugh. ‘How lucky for me; it seems that I’m famous!’

Even at this moment, she did not show fear, although she knew instinctively that this was the end of her time working for the escape line. ‘So that’s it then, is it, Pat?’ she asked. ‘Should we perform just one more escape?’ ‘Yes,’ O’Leary replied. ‘Time for The White Mouse to leave Vichy as quickly as possible. But you must not draw attention to the fact that you are leaving. You must walk out of the door as if it is any other morning and as if you will be back very soon. You must not take a suitcase or your belongings.’

‘What about Henri?’ Nancy asked. ‘Can I at least take my husband as an accessory?’ The humour she typically used as a shield – or perhaps, more accurately, a weapon – during difficult moments was in full force that evening.

‘That’s up to him. You could legitimately both be leaving the house together for an outing or errand, rather than going alone. I’ll leave you to discuss it with him,’ O’Leary said. But the look on his face made it clear that Henri would be in great danger if he chose to stay. ‘You know the network, Nancy,’ he continued. ‘You know the routes. The safest thing you can do right now, the best thing for both yourself and the Resistance, is to head out of Marseille to the Pyrenees and into Spain as quickly as you can.’

They shook hands – a rather formal goodbye for two people who had worked together so intensely, always on the cusp of so much danger. Nancy wondered if it would be the last time that they would meet.

After O’Leary left, Nancy went to find her husband in his home office to explain the situation. Henri decided that he should stay in Marseille, at least for a short time. It would be easier, he thought, and safer, for Nancy to leave the country alone. He also felt a great deal of responsibility to the community in which he had lived his entire life: to the employees at the factory, to friends and neighbours that he still trusted. He told Nancy that he had too much to settle before he could leave.

‘I’ll follow you, Nannie,’ he promised her. ‘It won’t take me long, but there are too many affairs that I must take care of here. We will meet in London once it’s all finalised. Despite everything, I can’t abandon my town or my legacy without a backward glance.’ Then they embraced, pouring out their fear for one another’s safety into the kiss.

Nancy did the only thing that she could have in that situation, even though she hated to leave behind Henri and the apartment where she had been so happy. France may not have been her birth country, but it had become home, and much of that was down to her husband and the place she had found in the world alongside him in Marseille. ‘I was French, except by birth,’ Nancy would often say.

She picked out the largest handbag she owned from her collection and packed it with essentials. She didn’t dare risk taking a change of clothes or a suitcase; anything too large might draw unwanted attention towards her, just as O’Leary had warned. If she was searched for any reason, too many possessions would only fuel suspicions. She wouldn’t have needed a clean dress on the usual outings she made, and at all costs she had to stick to her usual routine and appearances. Nonetheless, she did take her make-up with her. It was a form of armour, and Nancy suspected that she would need every tool in her arsenal to escape, considering the Gestapo had put her at the top of their ‘Most Wanted’ list.

She also packed money and jewellery as discreetly as she could, tucking them inside the lining of her bag. She took some of the false identification papers that the Resistance had provided her with, but left behind everything that identified her as Madame Fiocca in the luxurious apartment she had so lovingly furnished four years before.

She pulled on her winter coat and adjusted her hat in the hall mirror, as she had done hundreds of times previously. Then there was nothing left to do but to take up her wicker shopping basket, as usual, tuck it into the crook of her arm and prepare to leave the house. This she suspected, would be the last time that she would ever step through her front door.

© Alice Sharman 2026, ‘The Gestapo’s Most Wanted - The White Mouse: The Life of SOE Agent Nancy Wake’, Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.