'Paras in Action'

The hazardous business of developing parachute training in Britain ... from a new history of the Parachute Regiment

In May 1940, when Hitler struck in the west, part of the Wehrmacht’s success lay in the shock and surprise of a new method of attack. Fallschirmjäger, landed by both parachute and glider, overcame supposedly impregnable targets in Belgium simply by landing on top of them to begin their assault. Britain had to catch up fast.

Jason Woods, a former member of the Parachute Regiment, tells the story of British paratroopers through their many deployments, from their very inception in 1940 to the present day in Paras in Action: Ready for Anything – The Parachute Regiment Through the Eyes of Those who Served. First published in 2022, this history has been very well received by those looking for firsthand accounts of various actions over the years. The whole account is informed by Wood’s experiences and those of his fellow Paras. A paperback edition will be released later this year.

The following excerpt looks at the very first months of the development of a Parachute force in 1940-41, when intrepid men risked everything just to get the enterprise started:

Chamberlain’s government had underestimated the importance of airborne troops and although the Air Ministry had already set up a parachute training centre, Major John Rock of the Royal Engineers had been put in charge with very little support or information regarding the plan for this new unit. The Germans had been preparing for war for six years and when the Fallschirmjäger (German paratroopers) emerged as a successful fighting force that used parachutes and gliders to drop into enemy territory to overcome opposing forces, the British people lived in fear of being invaded by this enemy from the sky.

When Churchill came into power, he immediately galvanised people into action. In his famous letter to Sir General Hastings Ismay, he called for a ‘corps of at least 5,000 parachute troops …’ and added, ‘Advantage must be taken of the summer to train these men …’ He wasn’t allowing much time for the development of this new force and the training centre leapt into action. Once established, the British paratroopers soon made up for lost time and proved themselves to be more than a match for their German counterparts as the war progressed.

The Central Landing School (later changed to ‘Establishment’) was sited at Ringway Airport, just outside Manchester, and with Churchill’s support, Major Rock could now be more proactive in training and building up the new unit of parachutists. Volunteers were called to form the first parachute force, named 2 Commando. They answered adverts put out across the forces network for involvement in hazardous work; there was no mention of the fact that they would be parachutists and barely any of them had experience with flying let alone parachutes. Training got started very quickly with a joint team of RAF and Army physical training instructors, who were literally thrown in at the deep end with no training equipment, no real experience and nothing to guide them. All they had were a few hundred parachutes and six old Armstrong Whitworth Whitley bombers. Nicknamed ‘Flying Coffins’, these planes were already obsolete due to their lack of speed and vulnerability to anti-aircraft guns.

Over the next two months, instructors worked around the clock improvising with makeshift parachute towers and old aircraft. They developed the training through a process of trial and error and quite a few injuries; sprained and broken ankles or dislocations were commonplace. Exercises were devised to strengthen the muscles required for jumping and landing, and they were taught some basic self-defence skills for close-quarter battle on the ground.

Working out where to jump from was a major issue. At first the rear turret was removed, and the plan for the volunteers in this new role was to stand up in the open turret and wait for their parachute to inflate from above and lift them off the plane in what was called the ‘Pull Off’ method. This only got as far as the testing phase with the PJIs (Parachute Jump Instructors) demonstrating its use. Unsurprisingly, it proved to be extremely dangerous, so they moved to cutting a hole in the floor of the aircraft. However, this had its own dangers, with men smashing their heads or faces against the edge as they exited the plane through the 3ft-deep ring of metal. The soldiers called it the ‘Whitley Kiss’ and it was the method of exit for a while before the new Dakotas came into service with side doors installed for jumping, which eventually became known as Para doors.

Training was intense as the new para recruits were put through their paces to increase their overall fitness and tactical awareness and learn how to jump from great heights and land with a parachute. It was an innovative method of insertion, but for the guys it was purely a form of transportation; the real work of a paratrooper started once they hit the ground. As they continued, adjustments and improvements were made through trial and error. They changed their initial clothing to be less bulky, with early versions of the Para Smock coming into use.

On the 136th descent the first fatality occurred, sadly killing Ralph Evans, who experienced a ‘roman candle’. This is a total malfunction of a chute, also known as a ‘streamer’, where the canopy has failed to open; it is just trailing behind the parachutist, and usually results in death. Unfortunately, it was relatively common during the Second World War for this to occur, and British paratroopers weren’t equipped with reserve chutes at this time. Thankfully this situation has been very rare since the addition of anti- inversion skirts to the modern canopies.

A new parachute, the X-type Statichute, was designed, which had the main advantage of opening well after the parachute had cleared the aircraft. Several men died or sustained serious injuries in the early experiments, although one man had a remarkable escape from what was described as a ‘hang-up’. The hook from the static line got caught in Frank Garlick’s parachute bag and he was left dangling from the plane, unable to get back into the aircraft or be released. The plane came slowly into land with its tail up and he was dragged along the ground on his parachute. Remarkably, he survived with only cuts and bruises and went on to serve in North Africa and Arnhem with great distinction.

It is a tribute to these pioneers that, despite the haphazard facilities and men being injured and killed in training, they stuck with it, determined to master the techniques, and get ready for some action. Former RAF Parachute Jump Instructor Rick Wadmore, who served for twenty years up to the early 2000s, gave his view, ‘It was literally flying by the seat of your pants stuff in the early days. However, once they realised what was the best way of getting the paratroopers out of the plane and onto the ground as fast as possible, then things settled down. The first parachutes were known as GQ X type, then they moved onto the PX chutes. They were only on to the PX Mark 4 by the mid-nineties when the LLP (Low-Level Parachute) was brought into service, which just goes to show the slow progression of this form of transport.’

There were many who refused to jump or just couldn’t meet the requirements but those that made it through demonstrated the characteristics of mixing humour with a ‘let’s just get on with it’ attitude. As one early paratrooper, Tony Hibbert, recalled in an interview with Paradata, ‘Everything was about laughter in those days.’ On one occasion he jumped out of a balloon at night wearing full mess kit and spurs because he needed to complete another jump for his qualification book and Para pay. ‘We had to have a sense of fun, to lighten up and not take life too seriously,’ he said.

After six months, 488 men had completed training at Ringway, and they were keen to be given a mission. The war was raging across Europe and North Africa and German bombers had been causing devastation to civilian populations in cities across the land. The guys were pumped up and ready to go but raids kept being cancelled and some began to ask to go back to their original regiments, purely so that they could be involved in the fight again.

By late 1940, things were starting to move fast. The Parachute Training Squadron (previously ‘school’) was officially named. Most of the modern- day paratroopers remember it as 1 PTS. For those at the time it was merely PTS, and only became 1 PTS when, later in the war, a second school opened for airborne forces in India. Then they looked for a powerful, unifying symbol to bond this new force together, so ‘Pegasus the Slayer of Enemies’ was designed by the artist Edward Seago, who at the time was completing his war service in the Royal Engineers.

© Jason Woods 2022, ‘Paras in Action: Ready for Anything – The Parachute Regiment Through the Eyes of Those who Served’. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.

N.B. The above images are not taken from this volume.

Affiliate Links

Recently on World War II Today ...

Tobruk Captured

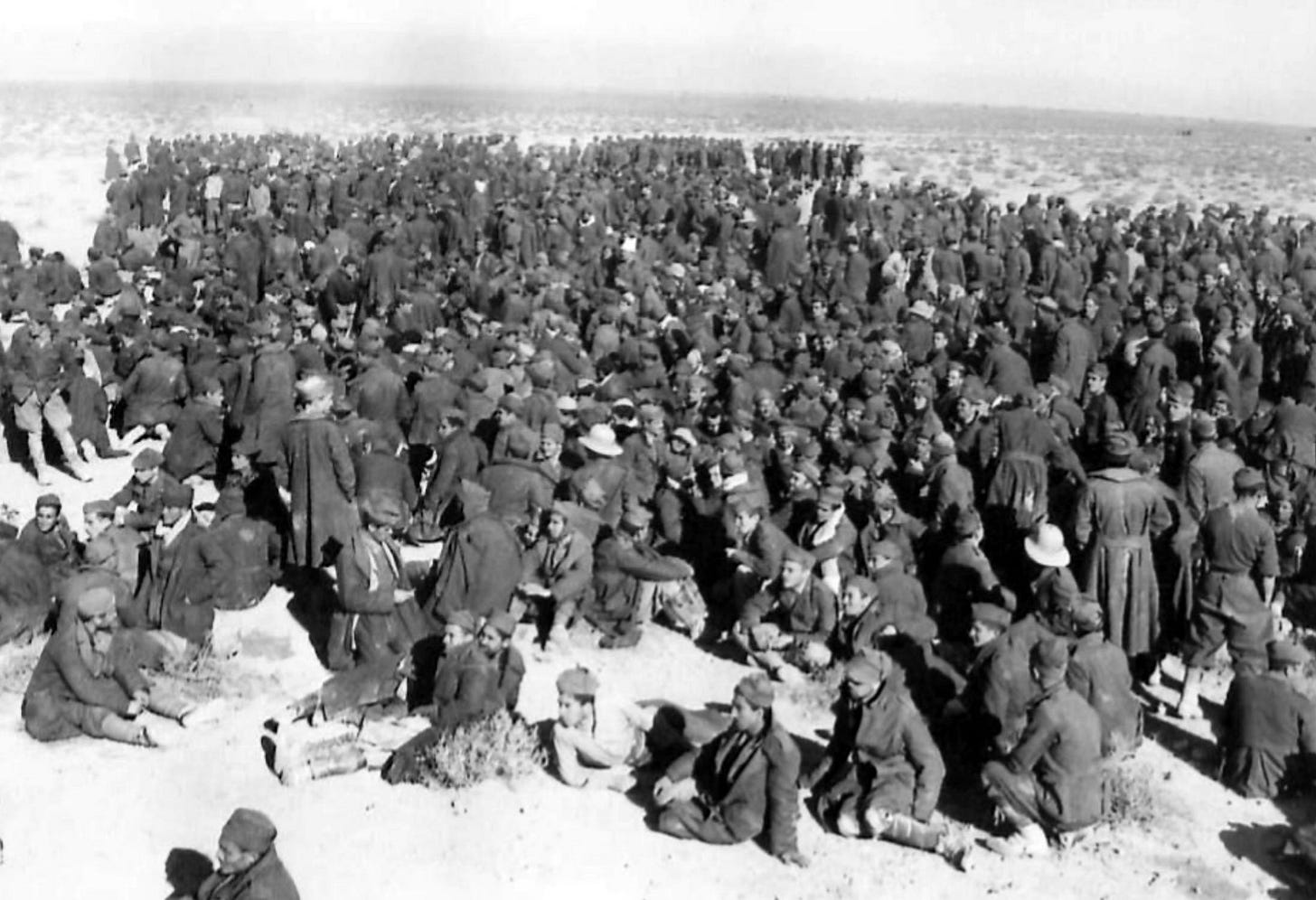

22nd January 1941: Demoralised and poorly led Italian troops have no hesitation in surrendering after the Australian assault

So we went back, and some anti-tank shells nearly hit us; they could penetrate our armour. We went back about a mile. There was pandemonium; no one knew what they were doing. The officers were all hidden. We got to where my tent was, jumped out, leaving the tank engine running. We got in a ditch, which had been dug to take water pipes up to a distilling plant. It wasn’t finished. But the ditch was handy because bullets were flying about.