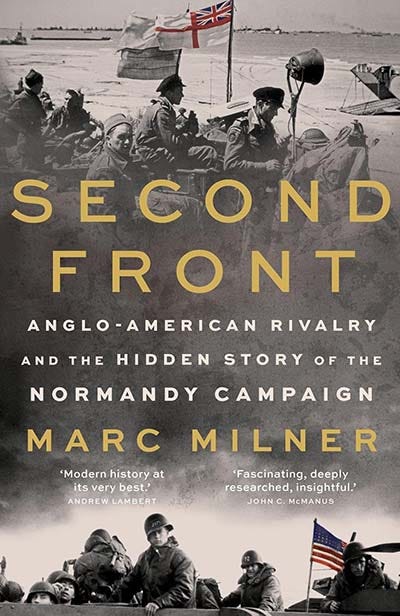

'Second Front'

A timely excerpt from a newly published history exploring 'Anglo-American Rivalry and the Hidden Story of the Normandy Campaign'

Anyone familiar with the story of D-Day and the Overlord plan for the liberation of Europe in 1944 will be aware of some of the tensions that existed within the Allied leadership. Although Eisenhower was the Supreme Allied Commander, the British Montgomery commanded both the British and American ground forces during the first battles in Normandy. But the tensions were much deeper than that. At the heart of the differences within the Allied camp were differing conceptions of the war aims.

These different perspectives, world views, and public perceptions of the contributions made by the men fighting dated back to at least the end of the First World War. There is a long ‘back story’ to untangle to put the decisions in Europe in 1944 in context. This fascinating story is told in Second Front: Anglo-American Rivalry and the Hidden Story of the Normandy Campaign, published earlier in 2025 by Canadian historian Marc Milner.

The following excerpt takes up the story at the end of 1940 as Churchill continued to lobby Roosevelt for material support, and American journalists contributed to a campaign to get US domestic support for Britain:

By the autumn of 1940 Murrow and other Americans were openly working with the BBC on propaganda films, perhaps the most important of which was the ten-minute short ‘London Can Take It’, narrated by Quentin Reynolds, correspondent for Collier’s magazine.

The film was released in Britain on 21 October and was an immediate hit. Warner Brothers in the US acquired it, and Reynolds used it during a speaking tour - without British titles or credits, just his name as narrator. An Oscar nomination followed the American release in December.

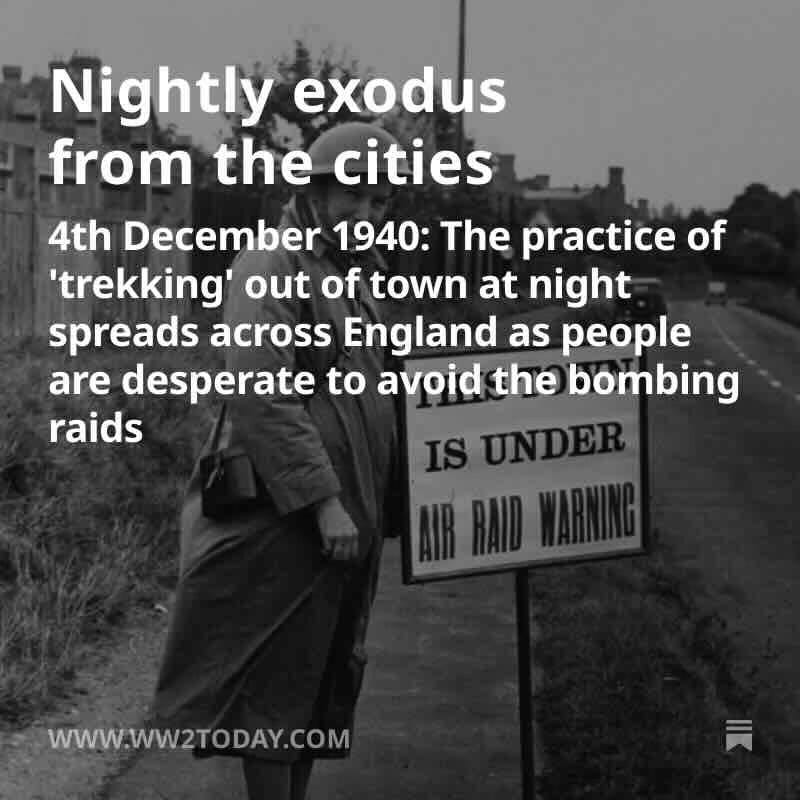

Churchill worried about civilian morale, but he also knew that the suffering, the little victories and the careful crafting of myths were all essential parts of the greater propaganda war. Even the Blitz itself was mythologised for public-relations purposes. In a globalised media market it was important that everyone, but especially Europeans under occupation and the dithering Americans, knew that Britain could take it.

… there was no denying in late 1940 that the German noose was tightening.

In late 1940 Churchills gravest concern was the impact of the German naval blockade: Britons needed to eat, but they also needed the sinews of war to continue the fight. The southern and eastern coast, especially the great ports of London and Southampton, were effectively closed by the Luftwaffe. It took nearly a year to reorient cargo handling, rail lines and manpower to the west, away from the immediate threat of air attack.

In the process, imports declined. There was a general tendency to attribute these declines directly to enemy action at sea rather than disruption at home, but there was no denying in late 1940 that the German noose was tightening. The U-boat attacks were part of a comprehensive German assault on Britain’s lifeline. At the end of 1940 Britain really needed America’s navy.

* * *

The architect of the plan that ‘saved’ Britain and made Allied victory possible was Lord Lothian, who persuaded Churchill to lay bare Britain’s situation and seek salvation from the Americans. And it was Lothian, upon his return to Washington in early December 1940, who ‘sparked off a major press and political debate which obliged him [FDR] to act’ . Reynolds concludes that it was Lothian’s innate understanding of how the American political system worked - and the critical role of the press and media in the formulation of policy - that ‘brought the issue to the attention of the opinion leaders and key policy-making groups whose support would be essential’.

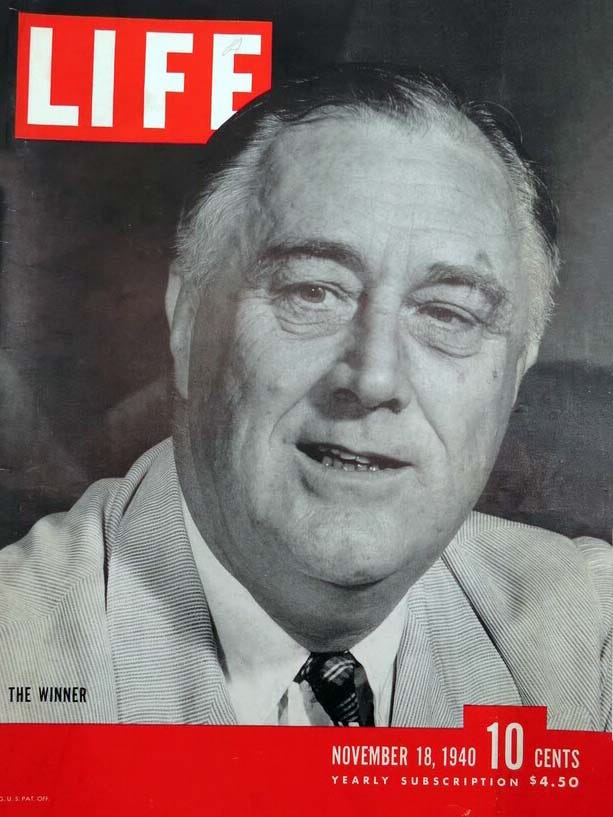

Roosevelt was already well aware that Britain was running out of US dollars and gold. But Roosevelt and others, not least Henry Morgenthau, the Treasury Secretary, believed that the British still controlled enormous wealth: perhaps as much as $18 billion in disposable assets. Had British sterling remained convertible the cash crunch would not have been serious. But the Americans wanted US dollars or gold.

Roosevelt was also well aware of Britain’s shipping situation. An internal British document, secured through the British Embassy in early December, confirmed what Americans suspected: losses to merchant shipping now outstripped Britain’s ability to replace them, by a wide margin. Churchill’s appeal to Roosevelt for help on 8 December 1940 runs to just 5,000 words. Eighty per cent of it is devoted to the U-boat peril, shipping losses and declining imports, and the prospect of the main German fleet - especially the new super-battleships Bismarck and Tirpitz - loose in the North Atlantic in early 1941. What Churchill really wanted was merchant ships and a decisive intervention in the North Atlantic by the US Navy to secure ‘freedom of the seas’.

‘Shipping, not men, is the limiting’ factor in British strategy, Churchill observed. But ships were not what the American press at the time - and subsequent historians — latched onto. When Lothian returned to the USA in early December he is alleged to have told reporters, ‘It’s your money we’re after.’ If so, John Wheeler-Bennett [ a British historian based in the US at the time] was surely right: ‘Never was indiscretion more calculated.’ This revelation spread across the American media like a prairie fire and forced Roosevelt’s hand. As Churchill explained, he wanted to attack Germany where ‘the use of seapower and airpower’ will allow its immense armies to be defeated in detail by smaller forces. ‘For these reasons,’ Churchill said, we are forming as fast as possible, as you are already aware, between fifty and sixty divisions.’

In view of the lingering threat of invasion, Churchill pointed out that most of these divisions would be kept at home. Nonetheless, ‘Even if the United States was our ally,’ Churchill asserted, we should not ask for a large American expeditionary army.’ What Churchill wanted - immediately - was help with the Battle of the Atlantic.

Churchill could not control the agenda, not least because Lord Lothian suddenly died. Having drafted a speech slated for Baltimore and given a final polish to Churchill’s letter to FDR, Lothian became drowsy and weak on Sunday, 8 December. His Christian Science beliefs forbade him from taking the simple treatments for uremic poisoning that would have saved his life. By Wednesday he was dead.

It is impossible to underestimate the impact of Lothian’s death on Anglo-American relations and on the fate of the British Empire. Americans of all socioeconomic groups felt some fondness for him. In Britain the news stunned those who knew the value of the man to Britain’s war effort. Only the death of Churchill himself, one commentator observed, would be graver.

Walter Lippmann observed in 1942 that Lothian’s death left ‘an almost complete intellectual vacuum’ in Anglo-American relations. Lothian was given a state funeral at the Washington National Cathedral, and buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Churchill eventually settled on Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, as Lothian’s replacement. The awkward nobleman epitomised everything that Americans thought was wrong with Britain, and he took months (perhaps years) to find his feet. However, Halifax was perceptive enough to know that Britain was losing the public relations war in the USA and within weeks of his arrival in Washington was petitioning for change.

Roosevelt was furious with Lothian for stealing a march on him and forcing his hand.

Meanwhile, Roosevelt was furious with Lothian for stealing a march on him and forcing his hand. Like many senior American officials, Roosevelt believed that Britain was hoarding its wealth. Churchill’s abject appeal offered Roosevelt and Treasury Department Secretary Henry Morgenthau an opportunity to achieve two long-desired goals: recover the debt from the Great War and, in Darwin’s words, ‘blast the sterling empire open’ . Dan Todman is more blunt: Roosevelt wanted to ‘defeat Fascism and imperialism, and to replace British with American power - which was exactly what he was doing as he manoeuvred to implement Lend-Lease’ .

Britain’s position in the American public eye might have been improved in December 1940 had a concerted effort been made to trumpet the success of General Archibald Wavell’s offensive against the Italians in Egypt. This was one of the great victories of the war, in which a small force of Australian and Indian infantry supported by British armour captured virtually all of Italy’s African Army.

But Wavell’s victory failed to make a splash. The MOI declined to launch a PR offensive in support of Churchill’s appeal. Rather, they urged ‘delicate handling’ and planned to confine ‘our propaganda ... to general statements and not attempt to specify the nature or extent of our requirements’ . ‘Is it not a scandal,’ Emery Reves opined in a letter to Churchill on 20 December, ‘that today the 11th day of our magnificent offensive in Africa, not one picture has been published in The New York Times about our victories?’ The dearth of gripping British stories and photos left the front pages of American newspapers to the Germans.

© Marc Milner 2025, ‘Second Front: Anglo-American Rivalry and the Hidden Story of the Normandy Campaign. Reproduced courtesy of Yale University Press.