'Taranto'

An excerpt from 'Taranto And Naval Air Warfare In The Mediterranean, 1940–1945'

The Fleet Air Arm raid on the Italian Fleet at anchor on the 11th November was a historic event, presaging an entirely new conception of naval warfare. The whole story is told by David Hobbs in ‘Taranto And Naval Air Warfare In The Mediterranean, 1940–1945’, which not only considers the context but, as the title suggests, the consequences in the theatre. This is a comprehensive examination of the Royal Navy's air strategy in the early part of the war and of this one raid in particular. It is illustrated with a wide range of contemporary photographs, many of which are rarely published, and some excellent schematic charts of the raid and other actions during the war.

The first of the following two excerpts is part of a detailed blow-by-blow account of how the raid unfolded. The second excerpt is part of Hobb’s Analysis of the strategic implications of the raid, as understood by the Imperial Japanese Navy:

The First Wave

At 1800 on 11 November Illustrious and her escorts were detached by Admiral Cunningham to proceed in accordance with their previous instructions while the battle fleet remained in support to the south. The weather at position X was fine with a light and variable wind at the surface and at higher altitude it was westerly at about 10 knots. There was a thin layer of cloud giving almost total cover at 8,000ft and the moon was three-quarters full bearing south. Observers were given a last- minute briefing while pilots checked their aircraft; once all twelve aircraft in the first range were manned and running, Commander Robertson shone a dim green light from Flyco that indicated the captain’s permission to launch; chocks were pulled clear and the leading aircraft marshalled onto the flight deck centreline. The first wave commenced flying off at 2035 and all twelve were airborne by 2040.

They formed up in a position 015 degrees 8nm from Illustrious and when all were in loose formation they set heading towards Taranto, 170nm away, at 2057.29 At 2115, flying at a height of 4,500ft, they entered cloud and several aircraft became separated, with the result that they did not all arrive over the target simultaneously. Williamson continued with eight aircraft in company with him, five with torpedoes, one with bombs and the two flare-droppers. Every observer maintained his own plot so that he could take over his own aircraft’s navigation if it became separated from the others in darkness or cloud and in fact there proved to be no problem as the aircraft that had become detached all attacked individually when they arrived at Taranto. Their task was made slightly easier by the dark mass of Cephalonia to the east and on the return, after four hours in the air, there was the comforting thought that they should be able to pick up the carrier’s homing beacon once they approached to within 50nm of it.

At 1955, shortly before Illustrious began launching her aircraft, an Italian sound location device at Taranto detected aircraft engines to the south. Ten minutes later other locators reported suspicious noises and alarms were sounded in and around the harbour. Guns were manned and the civilian population moved into air raid shelters. One battery even began firing a precautionary box barrage but ceased when the sound of engine noises faded. The intruder had apparently turned away and was almost certainly the RAF Sunderland of 228 Squadron searching the Gulf of Taranto for enemy surface forces.

Three-quarters of an hour later further engine noises were detected and a second alert was sounded but, as before, they faded and the all clear was sounded. At 2250 the sound locators began to detect the first wave of Swordfish as they approached from the south-east and a third alarm was sounded. Again some shore batteries began firing a box barrage and the flash from gunfire and exploding shells acted as a beacon to guide Williamson towards the target. The weather at the target was fine and clear like that in position X, with a light surface wind below a thin overcast.

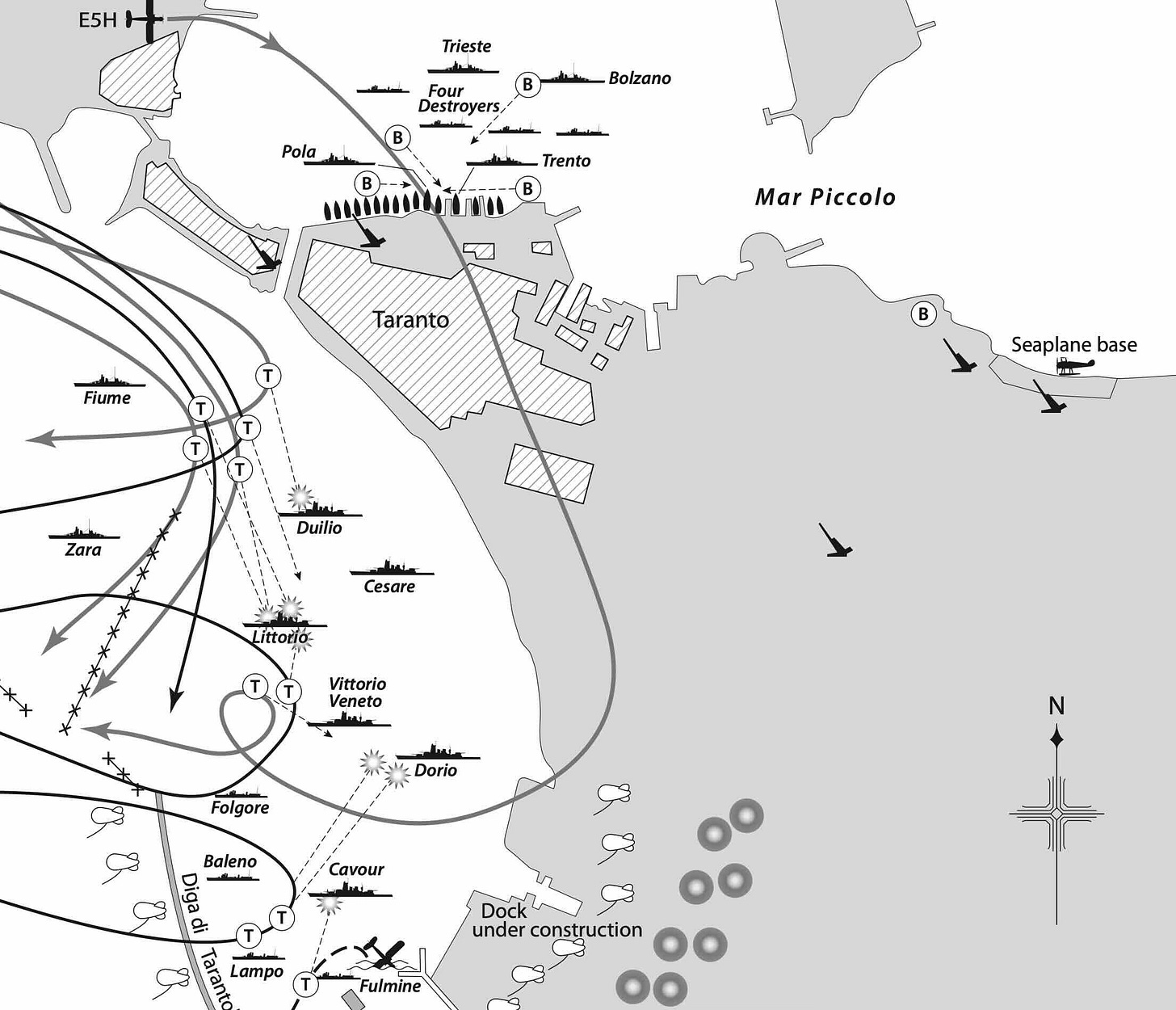

The moon was three-quarters full to the south at an elevation of 52 degrees at 2300. By then the missing torpedo aircraft, L4M, had re-joined the strike force, having made straight for the target to await the others and it was probably this aircraft that was responsible for the second alert. The strike aircraft found the six Italian battleships moored roughly three-quarters of a mile from the eastern shore of the Mar Grande and partially protected by the Diga di Tarantola breakwater, encircling lines of barrage balloons and a zareba of anti-torpedo nets.

At 2256 Williamson detached the flare-droppers L4P and L4B to seaward of Cape San Vito and they came under fire from several batteries as searchlights probed for them. Both were at 7,500ft and at 2302 Kiggell in L4P began dropping a line of 4.5in magnesium flares at half-mile intervals in a north-easterly direction to the south-eastward of the line of barrage balloons that protected the landward side of the anchorage. They were set to fall by parachute and ignite to burn from 4,500ft downwards. Having dropped his flares and waited for fifteen minutes to see that they illuminated the target area correctly, Kiggell carried out a dive-bombing attack on the oil storage tanks a quarter of a mile inland from the anchorage.

Lamb, in L4B, was briefed as the standby flare-dropper and after checking that L4P’s flares were functioning correctly, he too bombed the oil storage tanks before turning for the return journey to the carrier. At 2315 the flares began to illuminate the harbour and Williamson led his torpedo aircraft down from the west over San Pietro Island, evelled off 30ft above the water and headed for the southerly group of battleships. As they were seen flying through the box barrage they were engaged individually by a number of close-range automatic weapons firing tracer from ships, anchored barges and shore batteries.

Williamson took a more southerly route before turning north-east to fly through the balloon barrage to aim at Cavour, the most southerly battleship. He allowed himself time to aim steadily at his target and released his torpedo at 700yds. It hit and a large explosion was seen on the ship’s port side. Unfortunately, his line of attack took him between the destroyers Lampo and Fulmine, which engaged him at almost point-blank range. After weapon release he broke away to starboard across the stern of Fulmine and was shot down, ditching near a floating dock.

Both Williamson and Scarlett, his observer, were picked up by a boat from the dock and made prisoners of war. They were both well treated by the Italian Navy and Williamson later recounted that they were regarded almost as heroes. Two nights after the strike there was an RAF air raid and they were taken to an air raid shelter full of Italian sailors; cigarettes were pressed on them and towards the end of the raid about twenty men sang ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary’ for their benefit.

...

Analysis

For those able to comprehend what had happened, the oily wreckage-strewn surface of the Mar Grande on the morning of 12 November 1940 marked the eclipse of the battleship as the dominant factor in naval warfare and the arrival of carrier-borne aircraft as the fighting core of the fleet. RN aviators had succeeded in doing what they had always believed to be possible despite opposition from the Air Ministry and a lack of complete understanding by some politicians.

The Imperial Japanese Navy certainly took note. A potential attack on the US Pacific battle fleet at Pearl Harbor had been war-gamed as a ‘classroom exercise’ by the Japanese naval staff college prior to 1940. An air strike on the US Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor would have been considered a viable plan since the British Mission to Japan in the 1920s led by William Forbes-Sempill had revealed plans for the Grand Fleet attack on the German fleet in 1918 with Sopwith T.1s.

However, the Japanese naval staff believed that the harbour’s shallow water would make a torpedo attack too uncertain and had, therefore, limited their conjectural plans to high-level bombing. Taranto showed the Japanese that, with careful planning and carefully prepared weapons, a torpedo attack on capital ships in harbour was not only feasible but represented the best method of achieving decisive results. As with the Italian ships, however, they were to discover that ships sunk in shallow water can be raised and repaired to fight again.

Taranto taught the Imperial Japanese Navy another lesson, perhaps just as valuable, the need for the largest possible strike force – mass. The RN had only used one of its three Mediterranean-based carriers for the Taranto strike and had not armed the largest possible number of aircraft with torpedoes. The small force that carried out the strike had sent three battleships to the bottom, which were out of action for the immediate future but further attacks carried out through the hours of darkness, even if the later crews were less well trained, could have caused even more decisive results. To me, the fact that the Japanese committed six fleet carriers to strike a decisive blow at Pearl Harbor shows that they understood the need for numbers.

© David Hobbs 2020, ‘ ‘Taranto and Naval Air Warfare in the Mediterranean, 1940–1945’’. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.