In November 1940, it became clear that the Luftwaffe had not been able to destroy the RAF, and that Hitler would not be able to launch an invasion of Britain until at least the Spring. But an equally dangerous threat was emerging. Hitler would force the British into submission with terrorangriff - terror attacks - nightly bombing raids on the civilian population. At the same time, he would starve the population by cutting off supplies from abroad.

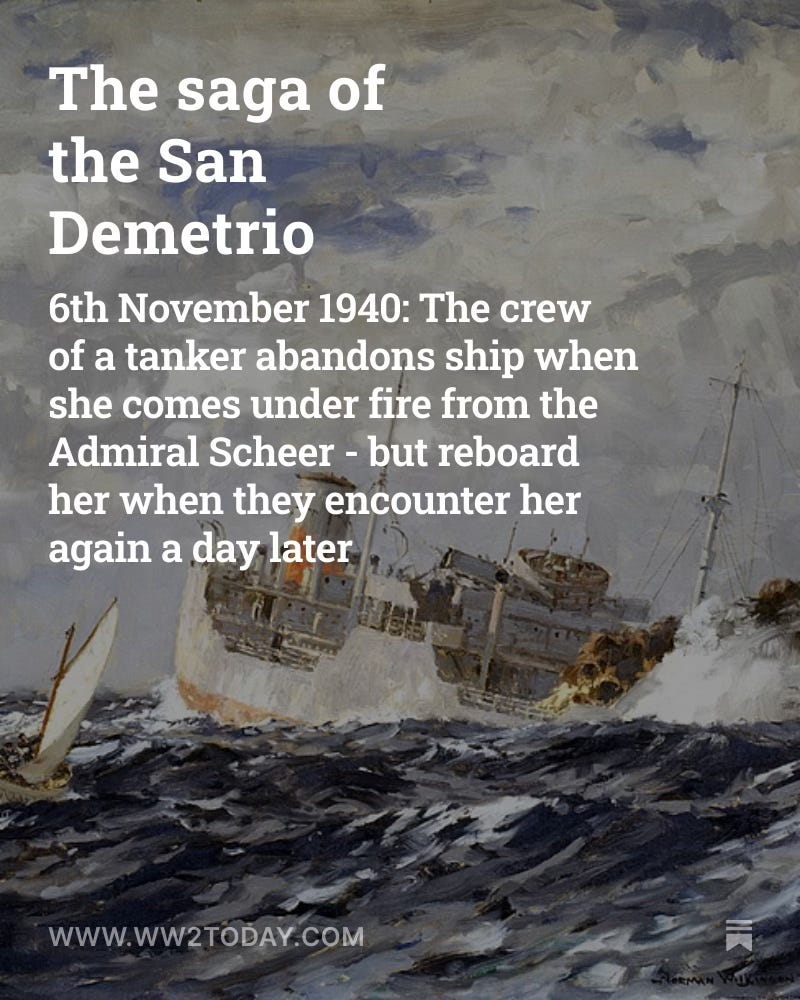

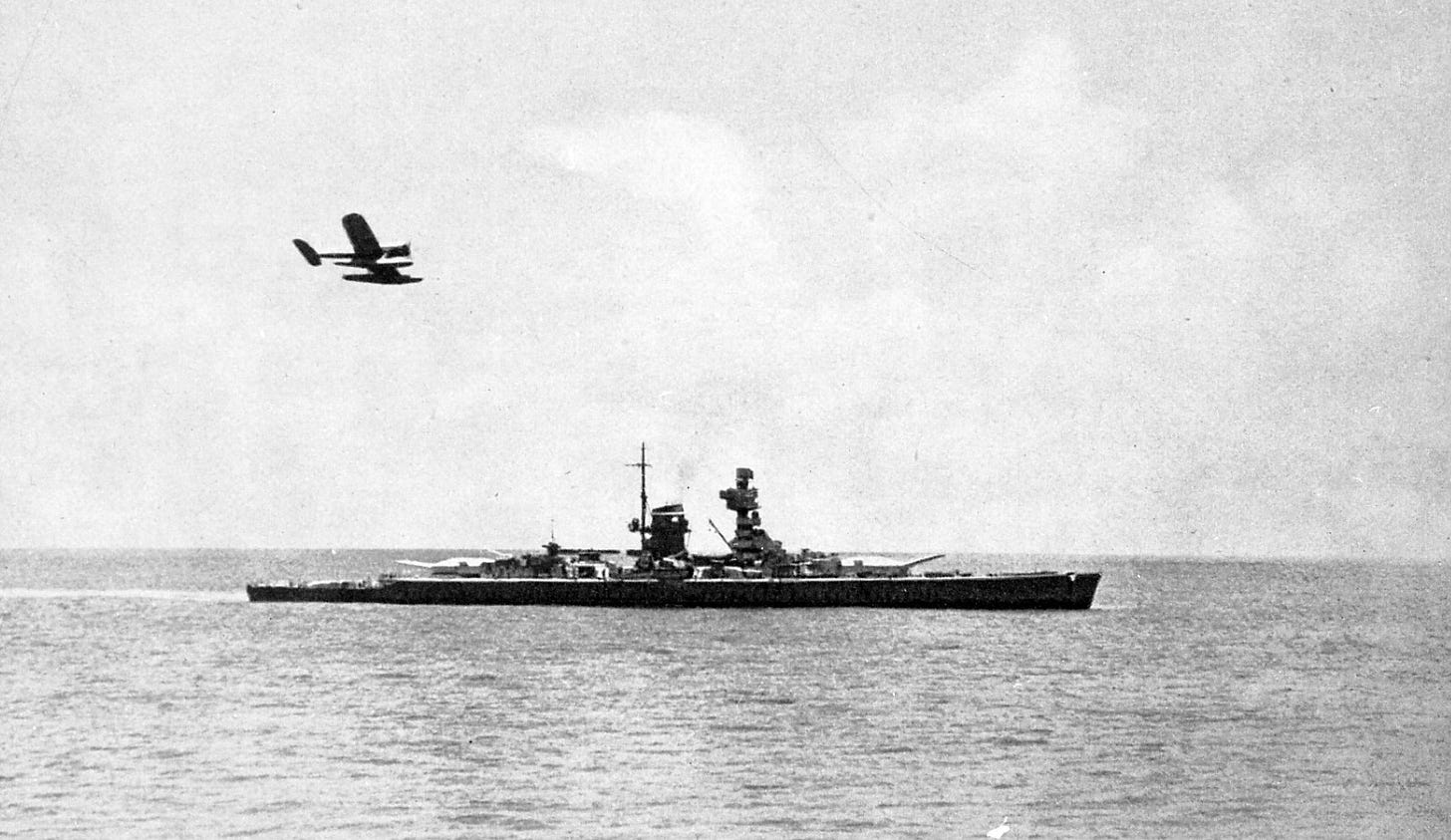

What became known as the Battle of the Atlantic was gathering pace. It was already noticeable that food was becoming scarce. When there were enough U-boats on patrol to gather a Wolfpack, they inflicted unsustainable losses on the merchant ships bringing munitions and food to Britain. Long range Condor bombers added to the destruction. And now another method of attack emerged - fast and well armed ‘pocket battleships’ would surprise merchantmen in mid ocean and blast them out of the water.

The epic battle between the merchant ships and the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer on 5th November is masterfully told in Convoy Will Scatter - The Full Story of the Jervis Bay and Convoy HX84. It is a tale of heroism and sacrifice when men went to certain death to give others a chance of survival. The heroic acts extended beyond those of the convoy leader Jervis Bay that became so well known.

The following passage describes the opening exchange between the German commander Krancke on the Admiral Scheer and Captain Fegen on the Armed Merchant Cruiser Jervis Bay:

Krancke knew he was being challenged to identify his ship, but he had no idea what the answering challenge was. He had examined the British ship through his binoculars, and any doubts he had had about her identity were settled. Her guns were clearly visible, and they were manned. She was an armed merchant cruiser. In order to gain time, Krancke told his signallers to repeat the ‘M-A-G’ back to his British ship, requesting that she be the first to identify herself.

This was an old ruse, and it cut no ice with the experienced Captain Fegen. He now knew he was confronting an enemy warship, and a very powerful one at that. The challenge he now faced was to fight or run. And only he could make the decision. A fight would almost certainly end in the total destruction of his ship, and in the deaths of many of his crew. Like any ship’s captain, his first duty was to see to the safety of his men; on the other hand, thirty-seven merchant ships carrying cargoes vital for the survival of Britain were looking to him for protection. It took just seconds to make the choice.

Fegen hit the alarm bells, and rang for full emergency speed. It was clear to him that he was hopelessly outgunned and outranged; his puny 6-inch guns were only effective up to 6 miles, if that. If he was going to fight, he must close the range as fast as possible.

As the Jervis Bay, battle ensigns streaming in the wind, surged forward, the Admiral Scheer turned broadside on, bringing all six 11-inch guns to bear. The time was 1700, with the weak winter sun slipping below the horizon, and darkness already closing in.

The bridge of the Jervis Bay had, by now, identified the stranger by her silhouette as a German pocket battleship of the Graf Spee class, and when he saw the ripple of flashes run along her side, Fegen knew what would follow. Petty Officer James ‘Slinger’ Wood later put Fegen’s fears into words:

It was a clear day, and we could see Jerry plainly in the distance. He was steering a course that would have brought him directly across our bow. But almost immediately he altered course, broadside to us. I knew what was coming. He wanted to get all his guns into action...

John Barker, a young hostilities-only gunner, remembered:

On the day of the action I was to keep the Second Dog Watch. At about four o ‘clock I went down to do a bit ofdhobeying. A little later the alarm bells rang. I grabbed my duffle coat -1 had on my service boots, trousers and football jersey. At my action station I could see a dark smudge over the port side - the Admiral Scheer. The Battle Ensign went up on the mainmast and very soon the first salvo of 11- inch shells came over...

The six 6701b projectiles, nearly 4,0001bs of hot steel and high explosive, came roaring across the intervening sky like a swarm of avenging hornets. This first salvo fell to starboard of the Jems Bay, close enough to shower the merchant cruiser’s bridge with salt spray, but causing no damage on board. The Scheer’s guns thundered again, and this time her shells exploded 100 yards off the Jervis Bay’s port side. Again no damage, but she had been bracketed, and every man jack on board, from the lowly galley boy to Captain Fegen himself knew what must happen next. Young John Barker was under no false illusions:

To have two turrets with three guns in each firing shells at you was pretty horrific. We had four vintage 6-inch guns forrard and three aft; they were vintage ones. I think one was dated 1894. They were open without turrets. They were no match for the Admiral Scheer...

At 1706 Fegen sent a coded signal to the Admiralty giving his unidentified attacker’s bearing, course and position; at the same time he signalled the Cornish City, ordering Commodore Maltby to scatter the convoy under the cover of a smoke screen.

The receipt of the distress was recorded in the Admiralty’s War Diary:

At 2006 today (London Time) Jervis Bay escorting HX 84 in midNorth Atlantic signalled that an enemy battleship was in sight and reports that the convoy was being attacked were received. Battleships Renown, Barham, Australia and Hood ordered to rendezvous. Five Town-class destroyers on passage to the UK ordered to spread out to locate Scheer and three of which were nearest the position of the attack were to close HX 84 to rescue survivors and attack raider if possible.

Whitehall now pulled out all the stops, and late that night the battlecruisers Hood and Repulse, the anti-aircraft cruisers Phoebe, Naiad and Bonaventure, accompanied by the destroyers Eskimo, Mashona, Matabele, Electra, Somali and Punjabi sailed from Scapa Flow for the position given by the Jervis Bay.

It was a classic example of the stable door being closed with a bang after the event. At 1100 on the 6th, when the rescue force was passing through the Minches, the Admiralty ordered Repulse, Bonaventure and the destroyers Mashona, Matabele and Electra to head out into the Atlantic towards the last known position of the Admiral Scheer.

HMS Hood, the anti-aircraft cruisers Phoebe and Naiad, with the remaining destroyers were sent to cover the approaches to Brest and Lorient. Bonaventure and Mashona were first to reach the mid-Atlantic position of the attack, but not until 0400 on the 8th, by which time only a few pathetic pieces of debris littered the sea. The Admiral Scheer was by then 1,000 miles further south.

And now the airwaves were alive with cries of outrage, as the merchant ships broke radio silence to call for help. Whereas the Jervis Bay’s message to the Admiralty had been in code, the merchantmen were broadcasting in plain language. Their frantic calls were picked up by Mackay Radio, on New York’s Long Island, and within minutes all the world knew that an Allied convoy was facing destruction in mid Atlantic.

The Scheer’s third salvo covered the 12 miles separating the two warships in 20 seconds, just as long as it took the frightening roar of the six spinning projectiles to reach the ears of those aboard the Jervis Bay.

It was then that Fegen came to terms with the impossible task he had set himself and his crew. At best, his 6-inch guns had a range of 8 miles, and he could not hope to lay a finger on the pocket battleship. But Edward Fogarty Fegen, third generation Navy, knew only that fire must be met with fire. He gave the order for his guns to open fire, even though he knew the range was too great. It was far better to make some sort of show of force, however futile. Nothing raised morale more than the sound of your own guns. And, God knows, his men needed that right now.

© Bernard Edwards 2013, ‘Convoy Will Scatter - The Full Story of the Jervis Bay and Convoy HX84’. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.