In 2015, the United States Military Academy produced an exceptional new history of the war. Based on the very same material that is used to teach cadets, this richly illustrated two-volume analysis covers many different aspects of the war, from the general economic and strategic perspective to some of the technicalities of tactics.

The West Point History of World War II contains a wide range of diagrammatic interpretations, some excellent modern maps, and many short biographies of the principal personalities. But the heart of this study is a series of chapters from world-renowned military historians examining different episodes of the war.

The following two excerpts illustrate how it examines tactics with diagrams, and how Robert M. Citino assessed the period of German victories:

Blitzkrieg Tactics

Although the Germans themselves rarely used the term Blitzkrieg, it has come to be the common term for the German way of war in the early years of World War II. It represents the successful combination of the internal combustion engine with leadership, doctrine, and modern equipment.

Blitzkrieg made the internal combustion engine the heart of warfare. The gasoline- powered motor gave the attacker the ability to move quickly with both armored vehicles and infantry. It made it possible for combined-arms forces to move at the same speed. It made effective air support possible.

The combination of trucks and armored vehicles—including tanks, armored cars, and armored personnel carriers—revolutionized the movement of armies. Artillery, engineer, signals, and logistics units could all move at the speed of trucks and motorcycles. The large-scale use of radio communications meant that attacking forces could report changing situations, seek assistance, and enable other units to adjust their plans and actions accordingly.

Air support was a vital component of Blitzkrieg. The control of the sky meant that German units could move freely, while their opponents had to constantly look skyward, worried that they would be strafed or bombed, that the bridge or rails ahead would be destroyed, or that their communications would be disrupted by downed phone and telegraph lines or radio towers. Troops could now be delivered by air, landing behind the lines and further disrupting the defense. Blitzkrieg changed the pace of operations, the relationship between offense and defense. A key question was how long it would take for the other nations to adapt to mechanized warfare.

As significant as the development of mechanized warfare was in World War II, it is important to remember that the bulk of the German Army was not mechanized. The Wehrmacht accomplished its great breakthroughs and rapid victories with relatively few armored and motorized units.

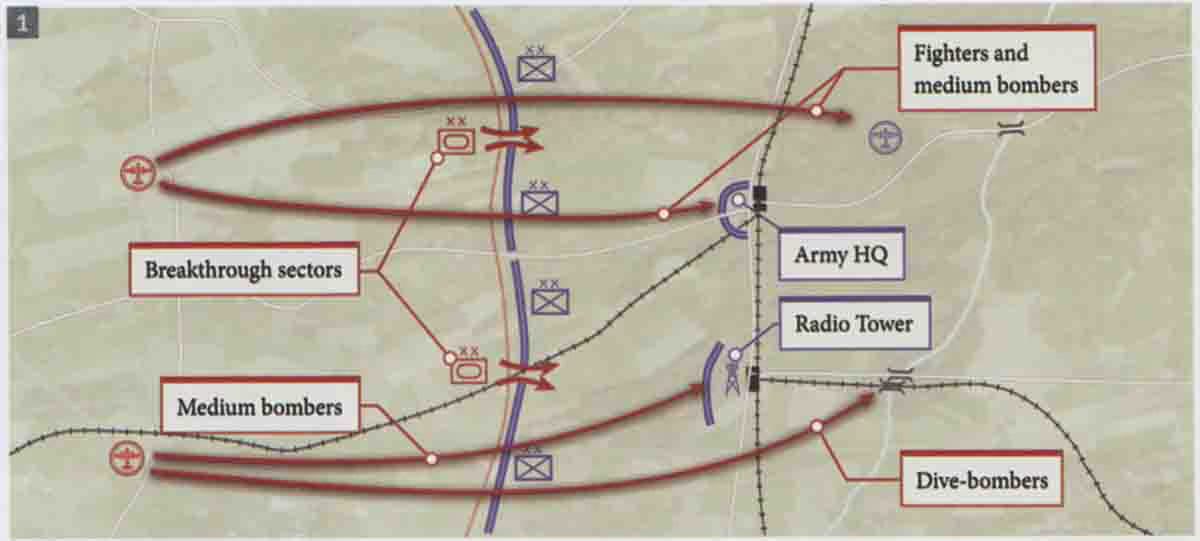

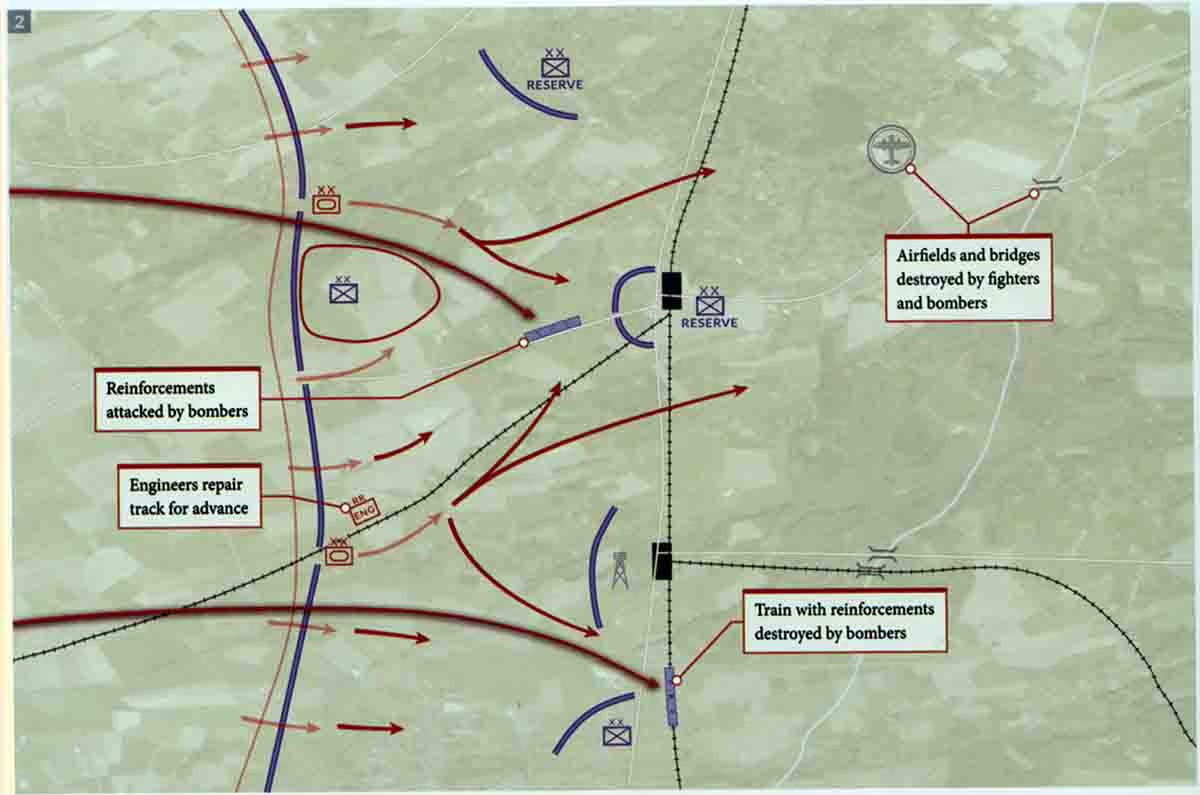

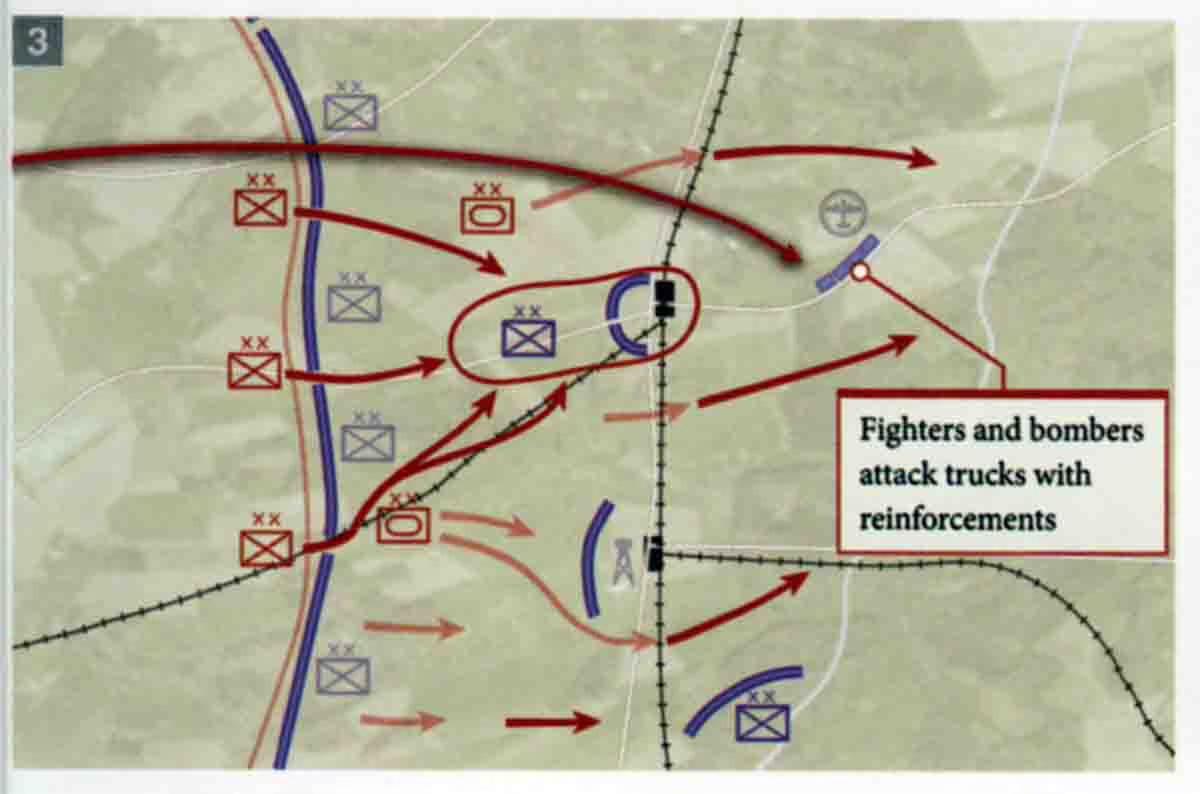

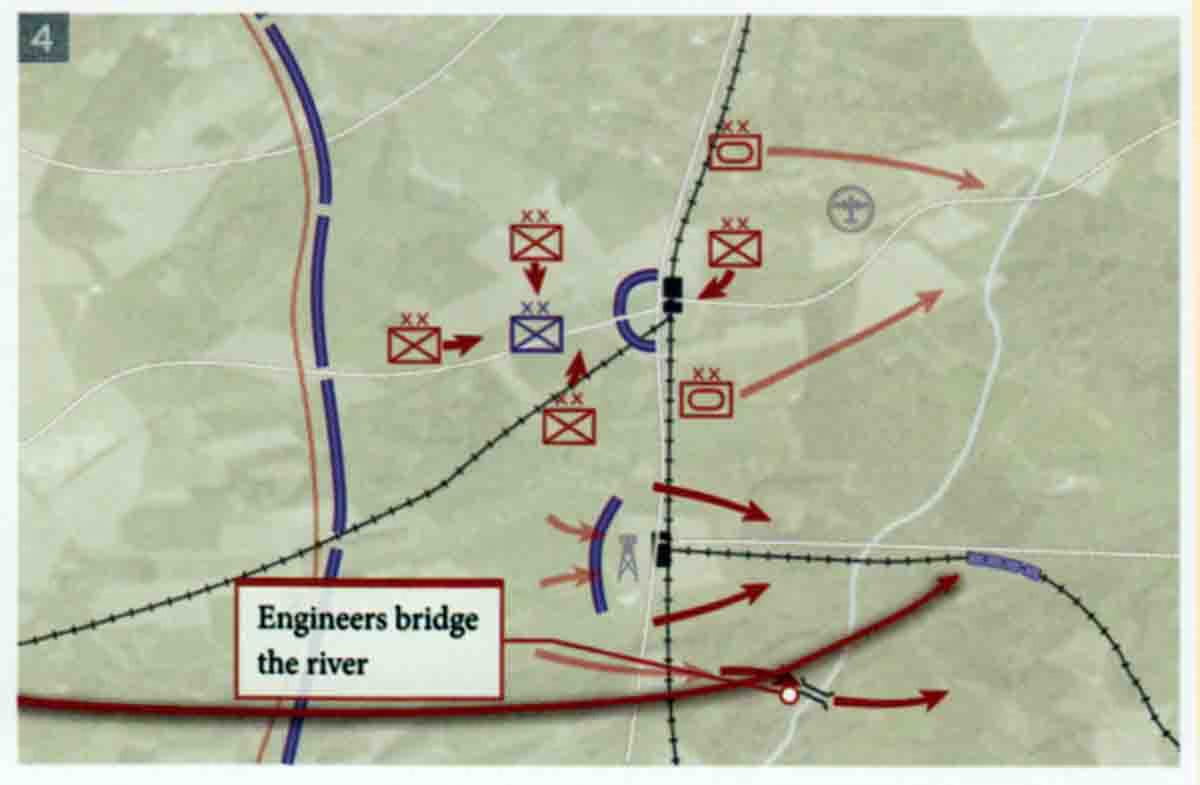

The following describes the generalities of a Blitzkrieg attack rather than any particular event.

1. German air units seize control of the sky over the battlefield. Fighters, medium bombers, and dive-bombers attack airfields, bridges, known headquarters, communications facilities, rail yards, and supply dumps to disrupt the ability of the enemy to mobilize and to react to the German ground attack. Initial attacks target enemy assets immediately behind the front or up to a couple hundred miles behind the lines. Fighter aircraft engage and destroy any enemy aircraft on the ground and in the air. Reconnaissance aircraft seek out enemy troop movements and concentrations and report any that are found so the bombers can target these locations.

2. With a breakthrough accomplished the armored/motorized forces begin driving through the initial enemy defenses and into the enemy’s rear. When German reconnaissance detects enemy troop trains or reserve units on the move, German air assets attack these elements. The Panzer and motorized infantry divisions continue moving into the enemy rear, bypassing or engaging enemy reserves as necessary when encountered. The German infantry deals with isolated enemy forces and marches as quickly as possible to maintain contact with the enemy and to keep up with the mechanized forces as best as they can.

3. German infantry units, in conjunction with mechanized forces, encircle enemy forces when possible. The infantry takes responsibility for the encirclements as soon as possible to free up the mechanized forces to continue forward movement. German air assets continue to respond to enemy troop movements.

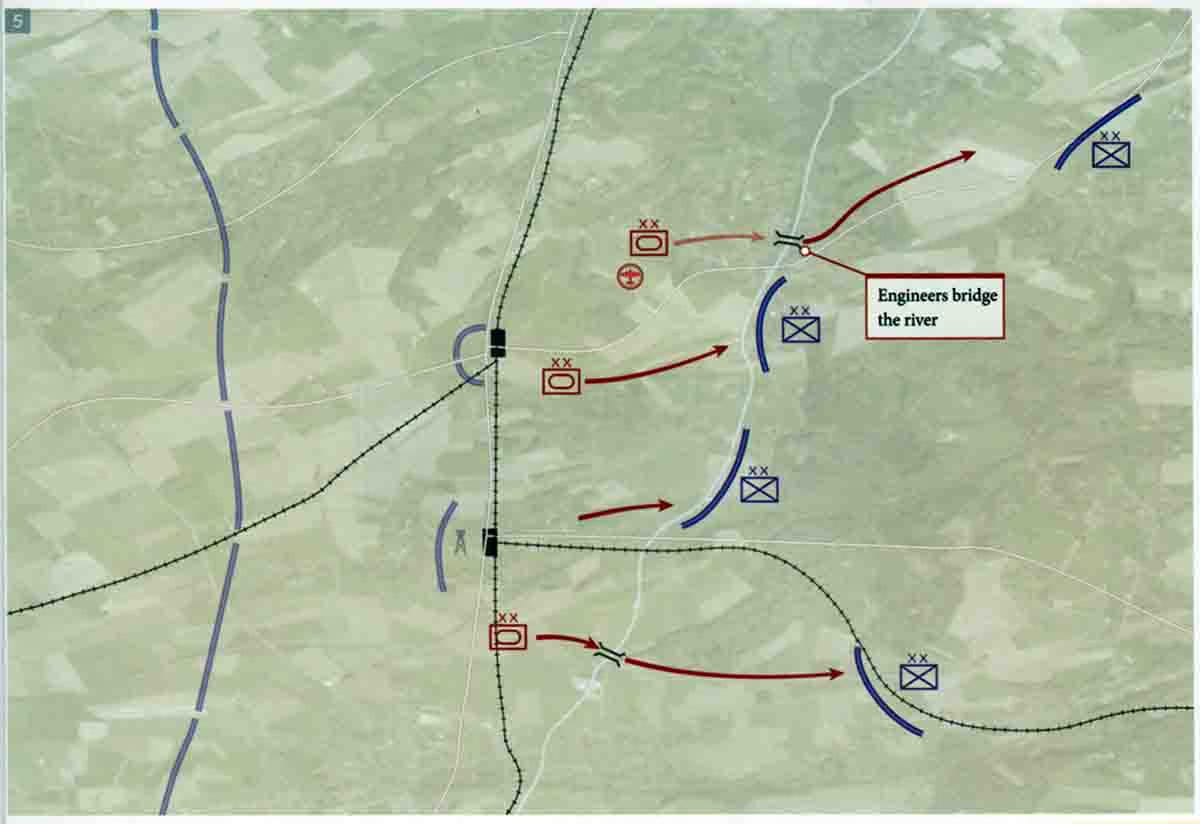

4. The enemy front is collapsing with a large force encircled. With the capture of the airfield, Luftwaffe troops move in to prepare the airfield for German use. Moving air units forward ensures continued air support of the advance. The defenders continue their efforts to establish a line of defense that will hold, but continue to be hindered at every turn by German air assets and motorized formations. When German mechanized forces run into an obstacle, their motorized engineers tackle the problem by clearing roadblocks and repairing bridges or constructing temporary ones.

5. The German Panzer units with motorized engineers cross the river before the enemy forces can prepare a defense. The defenders attempt to establish a new line but can’t move fast enough because their transportation and communications have been disrupted. It appears that another pocket is forming. The German movement is so quick that it is extremely difficult to coordinate a defense. Whereas the defending forces could react more quickly than the offensive forces in World War I, the offensive forces have the advantage in the early days of World War II. The result in the period of 1939-41 was a series of rapid defeats for those encountering Blitzkrieg for the first time.

The following excerpt come from Robert M. Citino’s chapter on ‘German Years of Victory’:

Conclusion

The first year of the war saw a series of decisive German victories, and the campaigns of this era continue to attract the attention of historians, military operators, and the general public. Certainly Germany’s achievement was an impressive one. It had used modern weapons and tactics—armor, aircraft, and airborne attack—to good effect, marrying them to a traditionally aggressive way of war that stressed independent armies linking up far behind enemy lines to create gigantic battles of encirclement.

Observers in the West might be able to explain away German victories in Poland, Denmark, or Norway. In all those cases, the opponents had been small or obsolete military forces. Case Yellow, however, in which the Wehrmacht dispatched the army of one Great Power and forced another into a humiliating evacuation from the Continent, compelled the entire world to realize the power of modern joint operations combining airpower with mechanized, combined-arms warfare. For that reason alone, these campaigns still reward careful study.

There is no need to romanticize any of it, however. A lot had broken right for the Germans in these operations. They had won so easily in Poland at least partially because the Poles two principal allies stood by passively and watched. They had overrun Norway and Denmark due to the failure of the Royal Navy to detect and intercept the German invasion flotilla, as well as the extraordinarily clumsy nature of the Allied intervention on land.

Perhaps the single most crucial factor in the triumph of Case Yellow was the Mechelen incident, which forced a last-minute switch in the German operational plan, to the Germans’ great advantage. In 1939-40, in other words, circumstances had conspired to hand the Wehrmacht a perfect storm of opportunities, and to its credit, it had seized every one of them.

And yet, despite the victories, any analysis of these events is still justified in asking: What exactly had the Germans won in these operations? Their armies had been at war for nearly a year and had now reached the English Channel. As would soon become clear, neither Hitler nor the high command had much of an idea about how to proceed from this point on.

Perhaps the best way to put it is this: the Wehrmacht now had to figure out a way to defeat Great Britain, an island that had not been invaded successfully since 1066 and that had not lost a war within living memory. As Hitler and his aides peered across the English Channel in the summer of 1940, the fog of war must have seemed particularly thick.

All the operational-level victories of the first year, as impressive as they had been, had not transformed the basic German strategic conundrum: how to defeat Great Britain without a navy. Certainly, the conquest of Western Europe had given the Germans a more favorable balance of resources, as well as bases for submarines and aircraft that could strike hard blows against Britain, targeting both its cities and its seaborne commerce.

Whether that would be enough to win the war was a question no one could answer yet.

©Rowan Technology Solutions LLC 2015, 'The West Point History of World War II - Volume 1'. Reproduced courtesy of Simon & Schuster.