'The Dunkirk Evacuation in 100 Objects'

This week's excerpt shines a light on some of the lesser-known aspects of Operation Dynamo

The many different aspects of Dunkirk 1940 have been widely studied and written about. But The Dunkirk Evacuation in 100 Objects: The Story Behind Operation Dynamo in 1940 offers a fresh perspective, uncovering some new stories that will be unfamiliar to many.

This richly illustrated volume does not attempt to tell a conventional history. By focusing on individual episodes, it tells much of the story through personal events and experiences in the battle. As well as being a useful addition to the history, this is a valuable prompt to visit many of the lesser-known locations associated with the evacuation, both in England and France and occasionally even further afield.

The following three ‘objects’ have been chosen to illustrate the diverse range of material contained in this volume:

The Tunnels at Dover Castle

Codename Operation Dynamo

Deep inside the famous White Cliffs of Dover is an extensive network of tunnels that became the headquarters of Bertram Ramsay who, since 24 August 1939, was Vice-Admiral Dover.

The tunnels were first constructed under the Castle in the Middle Ages to provide a protected line of communication for the soldiers manning the northern outworks of the castle and to allow the garrison to gather unseen before launching sorties against besiegers. The fear of invasion by the French in the Napoleonic Wars led to Dover being powerfully garrisoned. Soon the castle was overflowing with troops and so to create further accommodation and storage space the tunnels were considerably expanded, the work being undertaken by French prisoners of war. When complete, the tunnels, seven in number, could accommodate up to 2,000 men.

After the threat from Napoleon had finally ended at Waterloo, the tunnels were used by the Coast Blockade Service but, in 1827, they were abandoned and remained largely so until the outbreak of war in 1939. In the early months of the Second World War the tunnels were reopened as an air-raid shelter and then converted into an underground hospital.

The tunnels also became the naval headquarters at Dover. The nerve centre of the headquarters was a single gallery which ended in an embrasure at the cliff face. This was used as an office by Ramsay. When he first arrived at Dover, he had not been impressed with the resources. As he wrote to his wife: 'We have no stationery, books, typists or machines, no chairs and few tables, maddening communications. I pray that war, if it has to come, will be averted for yet a few days.' A succession of small rooms leading deep into the chalk away from Ramsay's office housed the Secretary, the Flag Lieutenant, the Chief of Staff (Captain L.V. Morgan) and the Staff office itself.

Beyond these was a large room used normally for meetings/conferences in connection with the operation of the base. In the First World War it had held an auxiliary electrical plant and was known as the 'Dynamo Room'. It was in this room on 20 May 1940, following his meeting in London the previous day, that Ramsay called a conference with his staff to discuss the evacuation of the BEF

At this stage it was hoped that 10,000 men would be rescued every twenty-four hours from each of the three Continental ports — Dunkirk, Calais and Boulogne - with the thirty or so cross-Channel ferries, twelve steam-powered drifters and six coastal cargo ships that had been allocated to the task by the Admiralty. The ships would work the ports in pairs, with no more than two ships at any one time in the three harbours.

During the meeting it also became obvious that a reorganisation of the base staff at Dover would be necessary to cope with the sudden rush of additional work. It was decided to set up this new body in the conference room itself.

Thus, it was in this former Dynamo Room that the preparation, planning, and organisation of the evacuation of the BEF from France took place. Two days, at 19.44 hours on 22 May, the Admiralty issued a blunt message to its various commands. The operation for which these ships are being prepared will be known as Dynamo.'

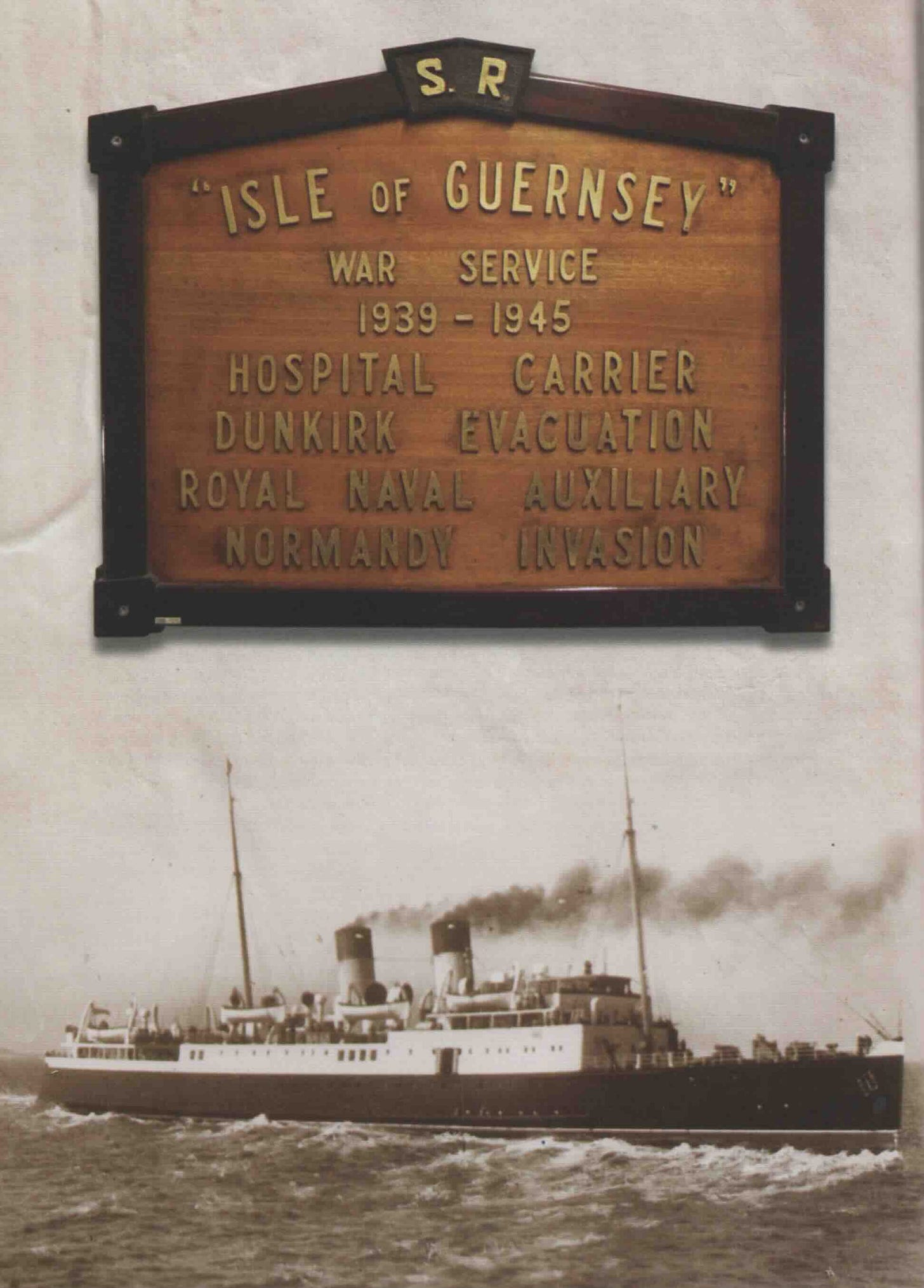

Steamer's War Service Plaque

Honouring the Hospital Carrier Isle of Guernsey

On a wall in the National Railway Museum, York, hangs a series of wooden ship's war service plaques from vessels that had been owned by the Southern Railway and had 'done their bit' during the Second World War. One of these plaques was for the steamer Isle of Guernsey.

Requisitioned from civilian service on 23 September 1939, Isle of Guernsey was converted to fulfil the role of a hospital carrier. Under the command of Captain E.L. Hill, Isle of Guernsey first sailed to Dunkirk', in company with fellow hospital carrier Worthing, at midday on 26 May, returning with 346 wounded men.

It was during her third crossing, on 29 May, that disaster struck, as Hill himself later recounted: 'At 5-16 p.m., having received orders, we proceeded towards Dunkirk ... At 7-30 p.m. an airman was observed descending by parachute close ahead of us and the vessel was stopped to save him. One of the seamen [Able Seaman J. Fowles] went down a rope ladder to assist the airman, but before he reached the bottom, 10 enemy 'planes attacked the ship with bombs, cannon and machine guns. By a miracle none of the bombs struck the ship, although considerable damage was done by the concussion, shrapnel, cannon shells and machine gun bullets. British fighter planes drove off the enemy and we proceeded towards Dunkirk with a terrific air battle taking place overhead.

'Arrived off the port at 8-20 p.m. we found it was being bombed and shelled, and we had orders from the shore to keep clear. Returning along the channel in company with two destroyers, we later received orders to wait until darkness had fallen and then return to Dunkirk.

'At 11-30 p.m. we entered between the breakwaters, the whole place being brilliantly lit up by the glare of fires, burning oil tanks, etc., and managed to moor up alongside what was left of the quay at 12-30 a.m. Loading commenced at once and by 2-15 a.m. we had taken on board as many as we could, numbering 490. All the crew and R.A.M.C. personnel behaved splendidly throughout, carrying on with their duties and doing their utmost to load the ship as quickly and as fully as possible, although the ship was shaken every few minutes by the explosion of bombs falling on the quay and in the water.

'Leaving the quay at 2-15 a.m. we proceeded out of the harbour and just outside we found the sea full of men swimming and shouting for help, presumably a transport had just been sunk. As two destroyers were standing by picking these men up, we threaded our way carefully through them and proceeded towards Dover. It would have been fatal for us to attempt to stop and try to save any of these men, as we made such a wonderful target for the aircraft hovering overhead, with the flames of the burning port showing all our white paintwork up.

Everything was comparatively quiet on the way across.' Travelling via Dover, Isle of Guernsey reached Newhaven at 11.15 hours, the latter having previously been designated as the main ambulance port for the BEF. 'No further trips were made to Dunkirk,' concluded Hill, 'because by the time our damage had been repaired, the evacuation was completed'.

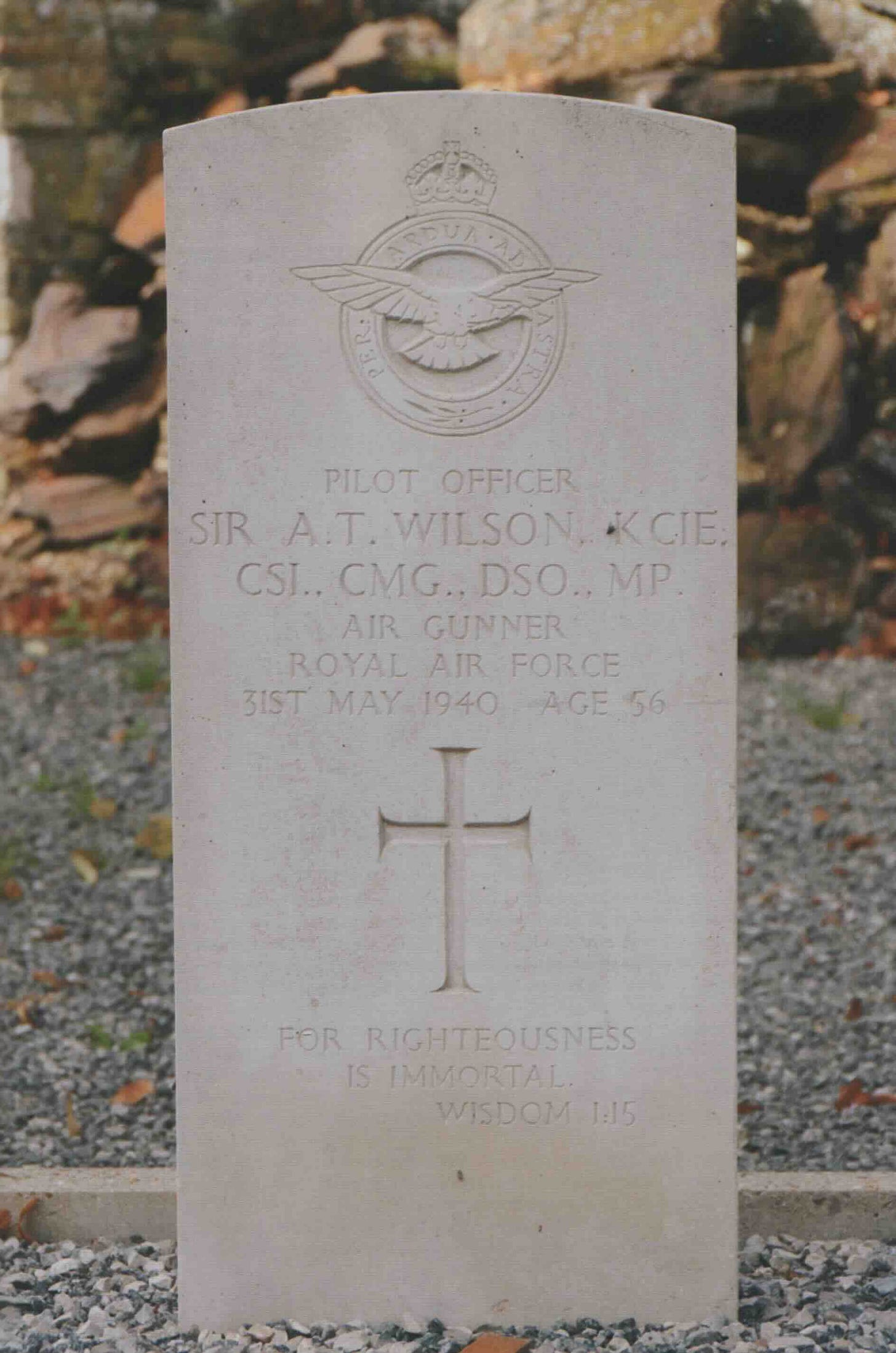

Grave of Sir Arnold Talbot Wilson

The Oldest and Most Highly Decorated RAF Casualty of the War

For its part in supporting Operation Dynamo, Bomber Command's losses continued to mount. Another Vickers Wellington which failed to return whilst carrying out a close ground support mission (see also Object 36) was L7791, a 37 Squadron aircraft flown by Pilot Officer William Gray. Gray had taken off from RAF Feltwell at 21.35 hours on 31 May. In total, thirty-three Wellingtons had been detailed to attack German positions near the Dunkirk perimeter at Nieuwpoort.

The cause behind the loss of L7791 has never been established, though it is known that Gray's bomber crashed at Eringham, a few miles to the south of Dunkirk.

One of the crew members of L7791 killed that night was Pilot Officer (Air Gunner) Sir Arnold Talbot Wilson KCIE, CSI, CMG, DSO. Aged 56, Wilson is generally regarded as having been the oldest and most highly decorated RAF airman to be killed on bomber operations during the Second World War. He was also the third Member of Parliament to be killed since the beginning of the war.

In an article published on 17 June 1940, Time magazine, on learning of the death of Sir Arnold, noted: 'Blue blood as well as red soaked the sodden plains of Flanders and the banks of the Somme last week as Britain's knights and lords fell with day laborers and farmers in the grim cavalcade of war.' One of those who remembered Pilot Officer Wilson was Squadron Leader (later Wing Commander) Cyril Kay - his squadron, 75 (NZ) Squadron, was also based at RAF Feltwell:

'Another personality of those now somewhat shadowy days - at one perhaps with his more youthful colleagues in an inflexible determination, yet cast in a very different mould - was he who bore the honoured name of Sir Arnold Wilson. Wearing but the one thin stripe on his uniform sleeve and the air-gunner's brevet on the tunic breast, the tall, erect, angular figure looked strangely at odds with the noisy mess surroundings, as well he might, for at some sixty years of age he already had behind him a career as distinguished and brilliant as it was indeed remarkable. The slightly sallowed complexion common to many who have lived long in tropical climates was evidence of his extensive foreign service; and as was Lawrence with Arabia, so, too, will the name of Wilson be always associated with Persia.

'Soldier, explorer, civil administrator, author, and politician. Sir Arnold as a young man had won the Sword of Honour at Sandhurst and then joined his regiment in India, leaving shortly afterwards for service in Persia ... Much later, as a roving Member of Parliament, he had interviewed and had discussions with both Hitler and Mussolini, and now here he was at Feltwell, the recipient of his country's highest honours and one of the most distinguished citizens of the land, fighting this latest war from the uncomfortable confines of a Wellington bomber's rear turret.

In resigning his Parliamentary seat [of Hitchin, Hertfordshire, which he had represented since 1933] he announced to his constituents that "I have no desire to shelter myself and live in safety behind the ramparts of the bodies of millions of our young men'', and his words were truly prophetic, for on the night of May 31, 1940, his plane was shot down over enemy territory, and he died as he would have wished - in the service of his country.'

© Martin Mace 2017, 'The Dunkirk Evacuation in 100 Objects: The Story Behind Operation Dynamo in 1940'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.