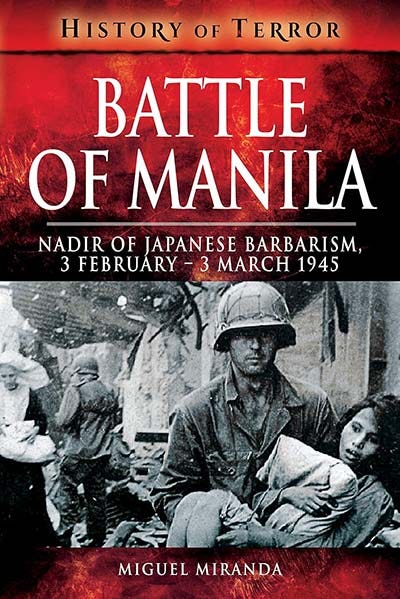

'The Battle of Manila'

The US Army faced one of its bloodiest urban battles of the war as it liberated the Phillippines amid widespread Japanese atrocities against civilians

In 1942, when the Japanese invaded the Philippines, General MacArthur had declared Manila to be an ‘open city’ - he would not defend it. He had sought to avoid unnecessary destruction to the beautiful neocolonial capital and unnecessary bloodshed amongst the Filipino residents. The circumstances of his return to liberate the island of Luzon could not have been more different.

Alongside the main Japanese forces on Luzon, who would fight a bitter rearguard action outside Manila until the end of the war, an independent force of Japanese Marines chose to fight to the death inside the city. They were soon engaged in a battle of unparalleled barbarity. They forced the US liberators to use maximum force to break into the city. Meanwhile, the Japanese Marines unleashed a series of terrible atrocities against the Filipino residents, many of whom were taken hostage. The story is told in Battle of Manila: Nadir of Japanese Barbarism, 3 February – 3 March 1945 (from the History of Terror series):

By late February everything north and west of the Pasig river was now in American hands. But the MNDF still controlled the walled city with untold numbers of hostages trapped inside. A hasty assault would have spelled disaster for the 37th Infantry Division so 105mm and 240mm howitzers were redeployed along the river’s edge. Two days of intermittent shelling produced two vital gaps in the stout walls of Intramuros.

On the morning of 23 February four battalions of 105mm howitzers, three battalions of 155mm howitzers, a single battery of 240mm howitzers and a token battery of 107mm mortars unleashed hell on the Japanese. The bombardment lasted a full hour, from 0730 until 0830 and was accompanied by salvos from the Shermans and the Hellcats.

It was imperative that the volume of high-explosive and armour-piercing rounds (from the tanks) softened up the buildings behind the walls and left them vacant. There were also flamethrower tanks at hand for when the combat got too intense. Companies of the 129th Infantry crossed the Pasig on flimsy assault boats that delivered them to the southwest bank near Fort Santiago where they entered the breach near the Government Mint and stormed the old citadel from behind. The 145th Infantry took the southeastern route, their objective being the 'Aquarium' at the far end of Intramuros facing Luneta.

It must be understood, contrary to what some American historians claim, that Intramuros was neither an ancient nor a medieval fortress but a remarkable example of late 18th-century fortification that the Spanish did their best to maintain until they lost the Philippines in 1898. Seen from above, each of the corners on the Intramuros's continuous walls were shaped like chevrons to give muzzle-loading cannon a wide field of fire.

The battlements were far from obsolescent in 1945 and two soldiers on a machine gun could lie crouched for hours, waiting to mow down oncoming attackers. Their relative concealment and the sheer thickness of the concrete around them made return fire useless. For this reason, an impenetrable smokescreen that included bursts of white phosphorus launched from the howitzer batteries concealed the 120th's and 145th's river crossing. Upon reaching the opposite bank the men hurried past the abandoned Post Office that stood between the wrecked Quezon and Santa Cruz bridges.

The 120th’s advance was led by L Company and once inside the walled city, movement became precarious. The colonial edifices like the Letran University were bristling with machine-gun nests and to the Americans' surprise, Filipino civilians were still fleeing from their Japanese captors. The situation became even more complicated once they reached Fort Santiago’s entrance adorned with the crest of St. James the Moor-killer [Matamoros). How the Americans managed to blow a hole through the old stone walls large enough for an M3 Sherman tank remains perplexing, but soldiers from L Company did enter the fort and annihilated the remaining defenders during the course of the night, with some 400 Japanese corpses evident in the morning.

It was in the dungeons below the fort where the latest atrocities were discovered: bodies piled on top of each other, all local men. It was ascertained the multitude had been crammed into cells and slaughtered with bayonet and gunshot. This was an horrific bookend to the purges of late 1944, when anyone suspected of aiding the guerrillas was brutalized at the fort. On 24 February the 145th did their best to protect an estimated 3,000 hostages, this time women and children, who had sought shelter at the San Agustin and Del Monico churches. The timing of the Americans' arrival couldn't have been more fortunate as bodies were again discovered in the bomb shelters underneath the Palacio del Gobernador just across the street from San Agustin.

This fitted a pattern where the Japanese used places of worship and other sensitive locations, such as schools and hospitals, to herd civilians into and kill them with cold-blooded efficiency. Evacuating the Intramuros survivors by truck arriving from Pasay, now occupied by the 1st Cavalry Division, proved difficult as the unprotected convoy was at the mercy of Japanese machine-gunners in nearby buildings. When motor transport was too hazardous, the women and children were escorted to the river's edge and taken aboard bancas tasked with depositing them in he ruins of Binondo.

A pontoon bridge was later assembled to allow the elderly and the wounded to cross on foot. But resistance in the walled city had ebbed at this point and the South Port Area, along with the Manila Hotel that had to be cleared floor by floor, was consolidated on the same day with help from squadrons of the 1st Cavalry Division's 5th and 12th Cavalry regiments. It was during this minor breakthrough when the strangest 'battle' in the vicinity of Intramuros unfolded.

After days spent clearing the Manila Hotel room by room, the South Port Area was overrun with relative ease as its defenders capitulated at the sight of Americans. They weren't Japanese, it turned out, but Chinese and Korean dockworkers hastily armed and left to fend for Themselves. The South Port Area was soon cleared and army engineers took over. The importance of the port was for supplies to arrive as soon as possible. These would hasten operations in the rest of Luzon and restore the Philippines as a staging area for an assault on the Japanese mainland in the near future.

Yet victory was far from certain. Hundreds of Rikusentai [ naval infantry units in the Imperial Japanese Navy] still controlled the administrative buildings outside Intramuros. As for their commander, Iwabuchi, there was no trace of his presence anywhere inside the walled city. The soldiers of the 37th Infantry Division never found a bunker or enclosure that served as a command post among the gutted buildings. It was later presumed Iwabuchi perished during the initial bombardment on the morning of 23 February.

In the two days since the successful assault on Intramuros had commenced, the Americans were burdened with clearing the last pocket of resistance in Manila. The job proved more difficult than anyone expected as nothing less than raw firepower would dislodge the enemy. Of course, it was terribly ironic for the XIV Corps’ battle-weary divisions to wreck the very edifices designed by well-meaning Americans and built for a would-be independent Filipino republic.

Laid out with impeccable taste outside the brooding Intramuros, the vital structures of which dated to the military-religious sensibilities of a bygone Spanish empire, the American colonial regime envisioned an inviting cityscape that embodied representative democracy. The urban planner Daniel Burnham was originally commissioned to lay out a series of structures as offices whence the Philippines could be governed. The result, done with the help of his assistant, William E. Parsons, was utterly charming.

© Miguel Miranda 2019, 'Battle of Manila: Nadir of Japanese Barbarism, 3 February – 3 March 1945 '. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.