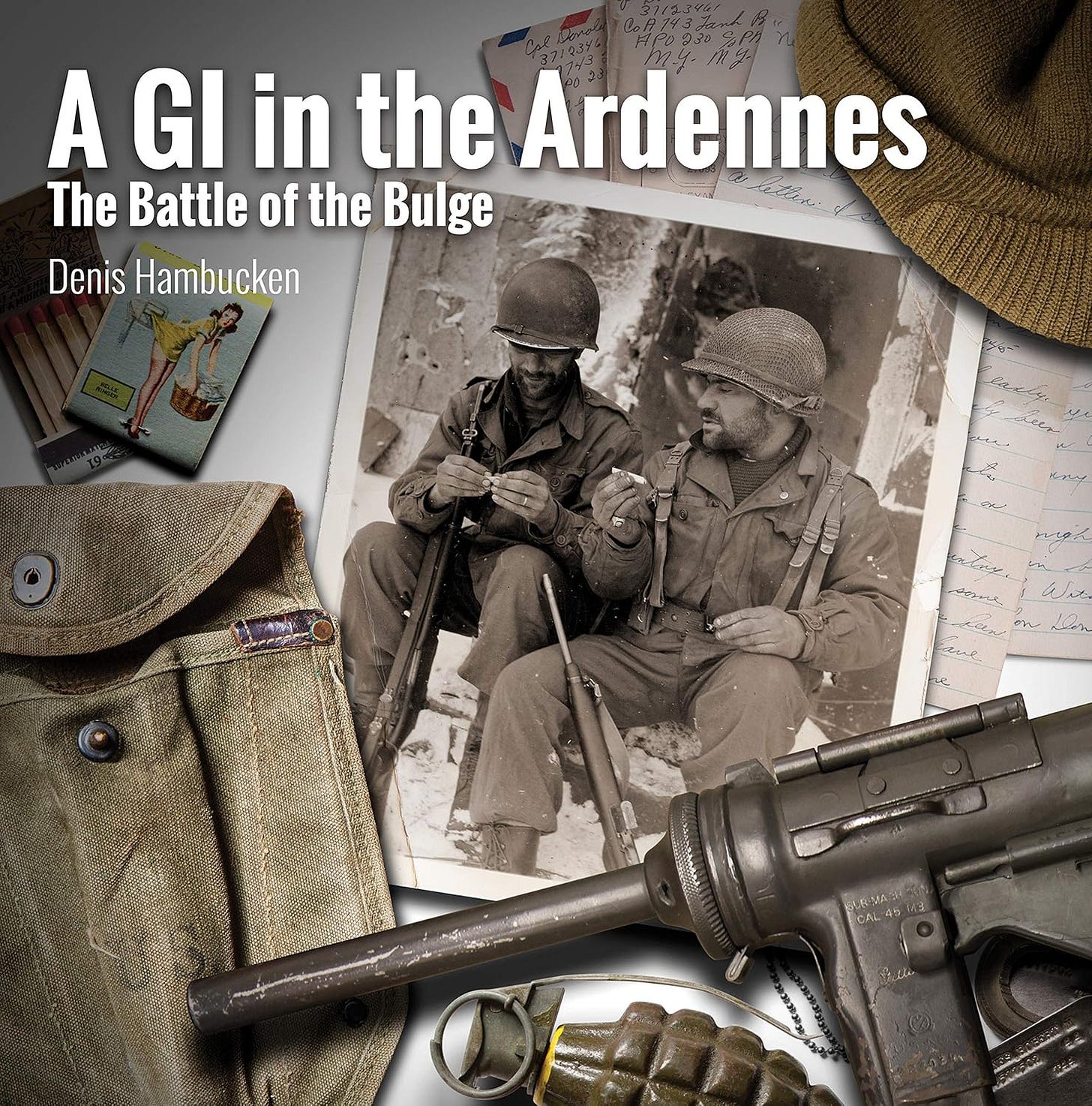

'A GI in the Ardennes'

A richly illustrated introduction to The Battle of the Bulge, with lots of background material on the conditions in which soldiers fought

This week, eighty years ago, Hitler was preparing for his last gamble. He had switched divisions from the east to the west and was preparing a surprise attack. Once again, the unpromising terrain of Ardennes would be the springboard for a thrust deep into Allied lines.

Many titles examine aspects of the battle, but this week’s excerpt focus’s on a general introduction. A G.I. in The Ardennes: The Battle of the Bulge was initially published in Belgium, aimed mainly at those visiting the battle sites in the Ardennes. A revised edition was published in English in 2020. It stands out as the most comprehensively illustrated guide to the battle available.

The pozit fuse is initially intended for anti-aircraft gunnery. A shell fitted with a proximity fuse only has to pass anywhere within 75 feet of an aerial target. Effectively, it magnifies airplanes to the size of blimps.

It proves effective in the defense of the Pacific Fleet against Kamikazes and in Great Britain against V1 flying bombs.

During the Battle of the Bulge, the proximity fuse is used to create air burst. An air burst is a shell that explodes above the ground rather that after hitting it. It generates a more powerful concussion and sprays shrapnel downward over a wide area.

To achieve air burst with time fuses requires complex calculations, and trial and error. By the time the gunner gets the timing of his fuses right, the enemy has time to hunker down or move.

The pozit fuse on the other hand, generates air burst with immediate and near total reliability, catching ground forces completely by surprise in the open.

In a letter to General Campbell, General Patton wrote: "The new shell with the funny fuse is devastating... I think that when all armies get this, we will have to devise some new method of warfare... I am glad that you all thought of it first".

There are many contemporary images from American and German sources, but the unique perspective of A G.I. in The Ardennes: The Battle of the Bulge is its modern colour photographs showing the weapons and equipment used by ordinary soldiers.

An excellent introduction to the battle for the general reader, and definitely of interest to those who are already familiar with the story. The following excerpt describes the German preparations:

German Preparations

Hitler understands that success will hinge on two conditions. First, the element of surprise must be preserved at all cost and the offensive has to adhere to a brisk timetable to prevent the Allies from regrouping and reorganizing. Second, the weather must be such that Allied airplanes remain grounded. To prevent leaks or intercepts, Hitler imposes strict telephone and radio silence.

Knowledge of the operation is restricted to a small circle of high ranking officers, all sworn to secrecy under penalty of death. Their movements and communications are closely monitored by Gestapo agents. The concentration of troops, equipment, fuel and ammunition under strict secrecy, represents an enormous logistical challenge.

Troops, tanks, and artillery are brought in under cover of darkness from as far away as Poland and Norway on a rail network that is relentlessly bombed by Allied planes. Arrived near their assembly areas in close proximity to American lines, they are carefully dispersed and camouflaged. To avoid telltale smoke plumes, troops are issued charcoal instead of firewood. The bulk of the troops would only be informed of the offensive the day before it is launched.

In spite of the Germans' best efforts, some American troops and civilians notice unusual or suspicious activity, but their reports are downplayed or dismissed. As he accompanied a six-men patrol from the 38th Cavalry Group somewhere east of Bullingen, 1s' Lt. Wesley Ross observed:

"Trees were being cut down with saws and axes, and tanks and other heavy motorized equipment were moving around over straw-covered trails to muffle their sounds. While watching this activity from a concealed position two hundred yards away on i the opposite side of the canyon, we listened to the big tank engines for some time and sensed that something unusual was afoot.”

Bill Campbell and his buddy "Rosie" of the 28th Infantry Division are manning a forward observation post. When they report increased activity with numerous trucks and tanks, the response from their headquarter is: "These must be ours." To which they replied: "When did we start wearing gray uniforms?"

The main focus of A GI in the Ardennes is the experience of the ordinary soldier, and alongside a number of sections dealing with personal memories from individuals who were there, there are many pages devoted to the details of their daily existence.

Alongside sections on a variety of weapons and other equipment, there is plenty of material relating to the individual GI - his uniform and personal gear, his field rations, and his access to mail are among many subjects covered. All are accompanied by some very good colour photographs - modern photographs which clearly illustrate their subject.

For example the following excerpt focuses on the business of digging foxholes:

Holes

Second only to his rifle, the infantryman's most important tool is his shovel. The M-1943 entrenching shovel (A) features a swiveling head that can be fully extended, angled as a hoe, or folded back for storage. The M-1943 gradually replaces the M-1910 shovel (B), although many soldiers prefer the T-handle of the older model. Wherever a unit stops, the first order of business is usually digging in for concealment and protection against shelling and small arms. If they are only stopping for a few hours or to bivouac for the night, soldiers dig individual slit trenches about two foot wide, two foot deep and as long as the soldier is tall. Remembers William Campbell of the 28th Infantry Division: "It was like digging a grave."

If the position is to be held, one or two-men foxholes are dug about four to five feet deep, usually with a step at the bottom, upon which soldiers can sit down, or stand to stay out of pooling water or to fire their rifles. According to army manuals, a foxhole with two feet of clearance above a crouching soldier protects him from tanks passing overhead, but German tankers learn to skid their treads over foxholes to collapse them and bury occupants alive.

The longer they remain in a defensive location the more elaborate their underground "homes" become. Foxholes are improved with roofs made of logs, doors or corrugated steel taken from nearby buildings and covered with earth for protection against tree bursts and mortar shells. The floor is lined with hay or pine boughs. Soldiers carve out shelves for supplies, candles and ammunition.

Frank Mareska of the 75th Infantry Division recalls that the much-dreaded German 88 guns left no time to duck:

“You only venture out of your foxhole if it was necessary. Pissing or shitting had to be done either in a K or C-ration box, period! Renderings could then be thrown out over the parapet of your foxhole.”

Larger holes are dug for machine guns and mortar positions, sometimes, entire vehicles are entrenched. When visibility is limited by falling snow, fog or obscurity, companies dig listening slit trenches some distance outside their perimeter to post sentries.

Hard-frozen ground is doubly murderous for the infantry: It makes shells more deadly as they explode on the surface, rather than penetrate the ground, and it also makes it much more difficult to dig in. John McAuliffe of the 87th Infantry Division recalls that setting up a mortar position involves digging a large, two to three-foot deep circular entrenchment in addition to individual foxholes for the crew: "Sometimes we were digging a hole and we were almost done and they'd say: 'OK, we’re moving out!'“.

After a long day of fighting, many are too exhausted to dig. In some places, the frozen ground is simply too hard for the entrenching shovel and few men carry the cumbersome MI 910 pickmattock(C).

Most vehicles carry full-size shovels, axes and pickaxes. John Di Battista of the 4th Armored Division recalls: "The mattocks were heavy enough to go through the crust of ground. Once the crust was broken out, entrenching tools could do the job.[...] We were desperate hugging the ground waiting for our turn at a pick."

Some units are provided with half-pound blocks of TNT with pull-type fuse lighters, fuses and blasting caps (D) to blast through the rock-hard crust of the frozen ground. An obvious disadvantage of the TNT method is the attention it draws. Rocco Moretto of the 1st Infantry Division recalls: "Everything was going beautifully but the TNT threw up heavy black smoke in the explosion areas. The enemy observing this quickly began to rake our positions with heavy concentrations of fire and we began to sustain heavy casualties."

Naturally, soldiers do not bother to fill their foxholes as they leave, consequently, Europe is riddled with millions of holes. It is not unusual for a foxhole to be occupied alternatively by American and German soldiers. After the war, It falls to landowners and farmers to fill in hundreds of thousands of foxholes and shell craters which are troublesome for machinery and hazardous to livestock. A post war survey of the grounds of the Castle of Rolley, an area of about 730 acres near Bastogne, counts no less than 2,490 foxholes to fill in.

© Denis Hambrucken 2020, 'A G.I. in The Ardennes: The Battle of the Bulge '. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd

Subscribe to World War II Today - Get 50% Off during December

Recently on World War II Today …

‘Street Fighting: Schiller Strasse Style’

These men first dashed across Gorch-Fock Strasse to House B and from here, at 8:30, Sgt. Brauch and his men jumped to C, first of the uncleared houses. As they ran across the street, a German machine gun opened up on them from down Schiller Strasse. No one was struck and the men reached House C.

This house had a hole blown in it at the ground level, leaving an opening from the basement and above the floor where a man could squeeze through. Germans fired from the cellar part of the hole as the men headed toward them to jump through the hole onto the first floor.

Nightmare at 30,000 feet

4th December 1944: The battle to exit a Mosquito bomber spinning out of control above Germany

He twists awkwardly out of his seat - his parachute on his back - and grabs at the joystick. Clutching it, he begins to rotate with the spin of the aircraft. Again he tries to reach down to help me. I stretch my hand up to his. But he seems to lift like a balloon, hover for a second, then shoots out of the black, gaping hole above him.

God Bless the GI Joes for Saving us from Evil