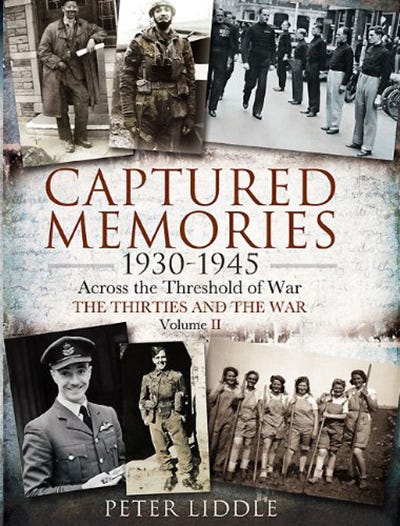

Captured Memories 1930-1945

The experiences of a British Officer captured at Arnhem, from a collection of memories preserved by the Second World War Experience Centre

For many years, Peter Liddle was the Director of the Second World War Experience Centre, where he helped capture the memories of over nine thousand people from all parts of the conflict, together with numerous personal documents relating to the war. Between 1968 and 1999, he personally interviewed over four thousand individuals from many different backgrounds, ranging from combatants of all ranks in all branches of the armed services - to housewives, ‘Bevan Boys’ (conscripted to serve as coal miners) and Conscientious Objectors.

A selection of some fifty such records were collected into Captured Memories 1930 - 1945: Across the Threshold of War: The Thirties and the War. This was a follow-up volume to Captured Memories, 1900–1918: Across the Threshold of War, another selection of Liddle’s pioneering work connected with the First World War.

The following excerpt comes from the interview of Captain John Killick, who, as a German speaker, had been recruited into the Intelligence Corps. He served with the Parachute Regiment and was captured at Arnhem. He describes his experiences in the final months of the war:

Our treatment was correct in the German sense. They respected us as having given them a hell of a good fight. They weren’t kind or benevolent. It led to my first experience of diplomacy in a way because the British officers all shoved into the big church kept wanting me to say to the Germans that under the Geneva Convention they must give us food and water and the SS men on the other side were saying: ‘Tell those bloody men, if they step off the pavement once again they will be shot,’ and I had to sort of interpret between the two, and I am bound to say that the SS men themselves didn’t have much in the way of food and water.

They were correct as regards us but they appeared on the other side of the square to be shooting Dutchmen in civilian clothes who had helped us, presumably because one of the saddest features of this whole thing was the great joy of the Dutch when we landed. They all came out and waved orange flags and gave us drinks and so on, but it was all, of course, premature, and the Germans stayed there in the end and we were defeated and those Dutch that had come that far into the open as to help us were caught, stood up against the wall and shot.

Interrogation of me by the Germans was minimal. If I were to have been wearing Intelligence Corps insignia I presume it would have been different. We were in the church for one night and then in a house in Velp, the pris oner of war cage of the 9th SS Panzer Division. They again took very little notice of us. Didn’t treat us too badly, brought food and tobacco and so on, and I was again being an interpreter in the middle of all this and tried to get some sense out of it. There was no formal interrogation at all until much later on.

Between Velp and the next village I managed to get away to no great purpose. I stowed away in the back of a German truck on its way to the German frontier, which wasn’t really very clever. While I was doing that the rest of them were taken to a place with great warehouses on the banks of the River Ijssel, and on the way a nasty event occurred where they were all in a truck guarded by the SS and the Dutch were waving at them.

The SS guard got off to remonstrate with the Dutch people and a couple of people took the opportunity of running for it, including Tony Hibbert. The SS guard came round and emptied his Schmeisser into the back of the truck, killing two people, wounding a lot more.

My escape attempt was when I formed up with a lot of other ranks and then hid under a tarpaulin in the back of this truck as they counted the rest off and left me on board and so, on we went. It wasn’t very pleasant because Allied fighters kept coming over and the truck had to stop and the driver would dive into a slit trench beside the road and I had to stay where I was, but anyway, we didn’t get shot up and unfortunately, when the driver stopped for petrol, needing the jerry cans under the tarpaulin, he discovered me. I was unarmed and that was that.

I was taken back to a town and handed over to a German Land Service Naval Battalion unit. I was very well treated and the next day sent on to the warehouses where the others were. After a few days we were entrained for a POW camp in Germany.

We passed through one or two camps on our way to the final camp, Oflag 79, near Brunswick. To find oneself a prisoner behind barbed wire was a nasty shock. Now as regards escaping, I as a German speaker joined the camp escape committee. We didn’t escape ourselves but we did our best to help other people organise their escapes and co-ordinate the efforts. Don’t forget, this was the autumn and winter of 1944. People thought the war might well be over by Christmas and frankly, a lot of our people saw no point in trying to escape. I would say the bulk. I managed to help with two escapes, both by friends of mine in the Parachute Regiment.

To cut a long story short, I created a diversion by starting an argument at the front gate in German with the guard while they walked out dressed as Germans in uniform. One was picked up straightaway, the other got a long way away and was only picked up when he was quite near the front line of action in the west.

I would say that morale varied depending how long you had been a pris oner of war. There were some people who had been captured in the Western Desert and had been prisoners I suppose for four years even. The camp had originally been in Italy. I think they had been shut off from life and become fatalistic. Not all, but they sort of lived dully from day to day. They were in the audience for those who had worked hard to produce and perform in various cultural presentations. There were a lot of people who did become deeply involved in cultural activities. We had a symphony orchestra, can you believe it, more or less, and we certainly had a lot of drama. Paul Schofield was a fellow prisoner at the time.

We didn’t go in much for sport. During the winter you couldn’t, and nobody had much energy in the spring of 1945 for football or anything like that. I suppose a few fitness fanatics tried it. Walking around the wire was a fairly common pastime but more for exercise than anything else. We had a very good camp library, which had come up with the camp from Italy.

I still have one of the books which I looted at the end of the war, and we had a dance band in which I played guitar and it was run by a trumpeter called Tommy Sampson, who I believe after the war became quite well known on the Northern circuit for running a big band of his own. I reckon we were jolly good and some enterprising souls ran a little nightclub called The Rumpot, where one played too with a small group.

I should explain that this could be done because there was a fairly sophisti cated system of exchange and barter based on a currency called Bully Marks. You fixed a price for a tin of bully beef at X hundred Bully Marks and anything else was priced in relative terms. There were no actual notes or anything like that. You could trade your Bully Marks for cups of tea or what ever in The Rumpot, and some people towards Christmas of 1944 were enterprising enough to take the prunes and the raisins and what not out of the Red Cross parcels and they unscrewed the lightshades from the ceiling, which were glass bulbs, and brewed up this stuff under their beds, and eventually managed to distil it into a clear white spirit, which took the roof off your mouth.

Yes, there were some who were dishonest, there was some thievery, stealing the rations of others. If anybody was caught, he tended to get thrown into the bomb craters, which were full of water. That was about all you could do really. I was in a room which only had three walls because one of the things that had happened to the camp before I joined it was that it was bombed by the Americans, and the Germans had never repaired the buildings properly, but I was very fortunate in being with three fellow officers from 1st Airborne Division and we had no trouble at all with regard to getting on with each other that I can recollect. One was a bit irritating because he had been a smoker and he suffered withdrawal symptoms but it was very civilized. There must have been people who couldn’t get on with each other and what they did, God knows.

There must have been a padre in the camp but I don’t remember him and there were church services. I have to confess that at the time I was not a churchgoer and I didn’t feel in great need of spiritual support in the religious sense. I don’t know where my spiritual support came from - recollection of girlfriends and home, I think, and family, of course.

No, we didn’t get regular mail and this was a pain but really such was the bombing that I feel sure that the distribution of mail would have been beyond the Germans, who could scarcely have rated it a priority in any case. I did feel sympathy for the German civilians in going, as a prisoner of war, through the Ruhr, as we did on our way down to Frankfurt, seeing the unbelievable degree of damage that was done to them. How they withstood all that and survived is beyond me. It was absolutely terrifying.

We had a wireless in the camp. It was a lifeline known as the Canary. How it got into the camp I don’t know. All I know is there was a very well organised system where every evening somebody came round and read out the BBC news, which had been heard on the transmitter, and we compared that with the German bulletins, which were posted up for us to read, and the differences were quite surprising.

As for the guards, the broad mass of them I think were Latvians. They were not Germans at all, and they were doing a job like a police job, you know, and when the Americans were within an inch of liberating us they all formed up outside with their suitcases packed and handed over their rifles - that did not go, of course, for some of the senior officers.

© Peter Liddle 2011, 'Captured Memories 1930 - 1945: Across the Threshold of War: The Thirties and the War'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd .

Affiliate Links

Recently on World War II Today ...

The platoon sergeant was really the key, as he usually had all the combat experience and general know-how. He did his hest to keep the officer out of trouble, which also kept us out of trouble. We learned to depend upon the platoon sergeant.

Infantry platoon sergeants were technical sergeants, highly regarded and worth their weight in gold. He carried an M1 rifle, bandoliers, and grenades. He was our backbone; don’t leave home without one.