'Normandy's Nightmare War'

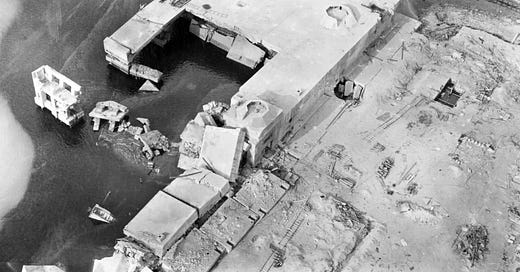

The bombing of the French port of Le Havre illustrates how the French suffered at the hands of both the Nazis and the Allies

More French civilians died under Allied bombing in northern France than British civilians died from German bombs throughout the whole of Britain during the whole of the war. It is a startling fact that is often overlooked in evaluating the campaign in Normandy.

Douglas Boyd’s Normandy's Nightmare War: The French Experience of Nazi Occupation and Allied Bombing 1940-45 is the product of years of research. Making use of many contemporary accounts, he builds a picture of what these years meant to the ordinary people of France, who had the misfortune to find themselves in the middle of a war being ruthlessly pursued by both sides. The context of German and Allied decision-making alongside these personal accounts makes this a comprehensive history, a valuable fresh perspective on the two campaigns that swept through the region, in 1940 and 1944, and of the years of occupation.

Even as Paris was liberated in August 1944 Hitler demanded that many of French ports should become ‘Festung’, fortresses that would hold out even as the rest of the war swept past them - denying their use to the Allies. The following excerpt considers part of the experience of Le Havre:

Starting in the late afternoon of Saturday 2 September at Gainneville a series of probing attacks were already taking place and more artillery duels were in progress. The meticulous M. Patouillard noted these in his diary, adding that explosions also continued all that day as the Kriegsmarine artificers continued demolishing port installations including the ship repair facilities of the Electro-Mecanique Company. The explosions, he wrote, shook houses and rattled windows all over Le Havre, with considerable damage to civilian premises from blast and flying debris. To this was added the noise of battle as some German-occupied areas lying outside the perimeter were liberated, tightening the screw on the garrison.

Colonel Wildermuth knew that the main Allied attack could not be long in coming. It being now more than two weeks since he had ordered the evacuation, he summoned Mayor Courant to meet him at 19.00hrs in the German HQ_- normally a no-go zone for civilians. There, Courant was given explicit instructions to evacuate the population the following day from the coastal zone of the pocket by two designated safe-conduct passages, one at Octeville in the north and the other at Harfleur in the south-east.

At Harfleur, too, special arrangements were to be made for the whores who had been working there for the German garrison. Posters announcing these arrangements were posted in the areas concerned next morning, but once again many of the people affected decided for themselves that, with liberation at hand, they had little to fear by staying at home. After some refugees preparing to leave via Octeville were injured by Allied artillery, the evacuation order was cancelled, sealing the fate of those inside the perimeter

That Sunday afternoon the heat was so torrid that mines began spontaneously detonating in a field over which British infantry was shortly tasked to advance.

At a planning and coordination conference in the tactical HQ of 1st British Corps at Foucart, General Crocker briefed the resentatives of the Royal Navy, RAF and the British and Canadian ground forces under his command on the requirements of Operation Astonia - the reduction of the pocket.

Logistics problems prevented the launch of the ground attack before the 147th Brigade and the Gordon highlanders of 51st Division arrived at earliest on 8 September - by which time Crocker wanted the defences reduced by artillery and air raids to minimise his men’s casualties in the final assault.

The official minutes of the conference reveal Crocker’s hope that showing the Germans the scale of the irresistible onslaught being prepared would pressure Wildermuth into surrendering, and thus make unnecessary a full-scale ground attack with heavy Allied casualties. The first step in this plan was to give the German garrison an ultimatum to surrender or suffer massive air raids and naval bombardment within forty-eight hours. After the first air raid, codenamed Astonia One and scheduled for Tuesday 5 September, a second ultimatum would be extended. If rejected, a second massive intimidation raid codenamed Astonia Two would be called in on 6 September.

If the Germans still did not surrender, the main attack codenamed Astonia Three would go in on Friday 8 September, supported by the Royal Navy and the RAF. In the event that Crocker’s ultimatum was accepted, a message would be sent to Bomber Command, calling off the whole plan: Astonia. Enemy capitulated. Cancel bombing (of Le Havre).

The meeting moved on to a discussion of the bombing, and the RAF liaison officer Group Captain A.H.S. Lucas was given precise coordinates of eleven targets, said to be German command points and troop concentrations in the city itself. These he was to forward to Bomber Command HQat Stanmore, where the aiming points would be calculated. Exactly how, why, and by whom the specific targets had been chosen, remains unclear.

On the evening of Sunday 3 September, Mayor Courant, who was spending his nights in a small bedroom in the town hall so as to be on hand for whatever emergency, was admiring the gardens in the Place de 1’Hotel deVille, thus far spared by all the air raids his city had undergone. About the same time, around 21.00hrs, on the perimeter to the south of Harfleur, Brigadier J.F. Walker summoned German representatives by loud-hailer to a meeting under flag of truce in Gonfreville l’Orcher.

There, he delivered the first ultimatum which included the warning about the scale of the coming attack and the dangers both to the German defenders and the civilian population.

At 09.20hrs on the Monday, with the local armistice for negotiations still in force, a British tank flying a white flag from the radio mast was observed by locals advancing towards the German positions, followed by a jeep bearing General Barker smoking his trademark pipe, and three other officers. Both vehicles stopped at a red-brick house on the main road. From the other side of the lines came a German staff car bringing a lieutenant with Wildermuth’s rejection of the ultimatum. Instead, he asked for a 24-hour truce to permit safe evacuation of French civilians resident in the pocket.

Failing that, he needed time to ensure their removal to areas where there were no military targets. Both requests were refused as stalling manoeuvres that would upset the Astonia timetable, and the point was made by Allied artillery shelling several areas of the city that afternoon, against a background noise of demolition explosions from the port area that lasted until 21.15hrs - after which, the night was relatively calm, with no Havrais realising that it was the last night on earth for many of them as the count-down clock for Operation Astonia ticked away.

Next morning Le Petit Havre newspaper announced that the evacuation had been halted. When a deputation of priests and local politicians begged Wildermuth to surrender, to save the population, his reply was understandably,

‘You should all have left by the end of August, as I ordered, but your people didn’t want to leave. Now, it’s the British who have refused to permit the evacuation. So, it’s nothing to do with me. I am here to fight.’

The civilians in the pocket were more interested at that moment in bread — now available only on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. A limited distribution of cooking oil was available, as were tins ofcondensed milk for those with the right ration cards, plus 150 grams of ersatz coffee. All over the city, people queuing outside the thirty-seven butchers and thirty charcutiers with whom they were registered could clearly hear the artillery fire from the perimeter, and took this as a favourable sign that the Allies’ final assault was beginning, with their liberation only hours away. What point was there, they asked, in the Germans continuing to hold out in Le Havre when British spearheads had already reached Antwerp in Belgium and the Americans were approaching Reims?

The answer was that the very speed of the Allied advance and the competing demands for motor fuel had made it an urgent priority for Montgomery to capture some of the Channel ports along the line of advance. Supply lines already stretched 400km to the rapidly advancing front from the Mulberry harbours and the French terminal of the PLUTO pipeline at Port-en-Bessin, north of Bayeux- which carried 4 million litres per day from a pumping station on the Isle of Wight.

Capturing Le Havre also meant control of the Seine estuary, making available the already liberated riverine ports of Rouen and Paris. With the overstretched supply lines thus drastically shortened, it seemed to many in the Allied chain of command that it would be possible to end the war by Christmas.

This was the pressure now on Crocker: to get the job done as rapidly as possible, using whatever force was necessary. But some of the troops under his command, like the Hallamshire Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Trevor Hart Dyke, had suffered up to seventy per cent casualties since landing in Normandy and most of the survivors were suffering severe combat exhaustion. It was therefore understandable that Crocker was prepared to use any means to keep Allied casualties in Operation Astonia to a minimum.

Throughout the morning of Tuesday 5 September the Havrais could not ignore the heavy shelling outside the city, accompanied by the continuing demolition explosions in the port area. A moment of unconscious humour was provided by Wildermuth’s Order of the Day:

It is suspected that agents inside the Festung are in contact with the enemy by carrier pigeon. Any pigeon seen flying out of the Festung is to be shot down.

The Allies’ experience in Normandy since D-Day had shown the importance of building in last-minute confirmation or cancellation of bombing raids that were planned several days in advance, in order not to kill one’s own troops by ‘friendly fire’ or waste bombs on a position that had already been neutralised. In this case, the RAF raid code-named Astonia One was to be either confirmed or cancelled by midday on 5 September by a simple transmission, in which oranges meant Go! and lemons meant cancellation, with another ‘target for tonight’ being selected from the list.

At midday, when oranges was transmitted, the die was cast. General Barker, commanding 49th Division, belatedly protested to Crocker that ‘history would judge severely’ a massive air raid on a target largely occupied by neutral French civilians, but it was in any case too late to cancel the raid then.

According the RAF Bomber Command campaign diary, on that day:

348 aircraft - 313 Lancasters, thirty Mosquitos and five Short Stirlings (of) Nos 1, 3 and 8 Groups - carried out the first of a series of heavy raids on the German positions around Le Havre which were still holding out after being bypassed by the Allied advance. This was an accurate raid in good visibility. No aircraft lost.

Shortly after 17.45hrs the Mosquitos from No 8 Group roared over the city from north to south, firing green marker rockets into the designated target areas. This was no night raid, nor did cloud obscure the target. At the beginning of September it was broad daylight and visibility was excellent- in technical terms: ‘9/10 THS cumulus, cloud base at 9,000 ft on take-off, with the cloud clearing on approach to target to 3/10 cloud cover and cloud base at 6,000-7,000 ft.’

The Mozzies were followed after an interval of five minutes by the first wave of bombers, all bearing the roundels of the RAF. People on the ground counted six waves of forty Lancasters each - although many traumatised Havrais counted eight or more waves, each lasting a terrifying six minutes. A total of 1,820 tonnes of high explosive and 30,000 incendiary bombs were dropped on squares 4826 and 4827 of the navigators’ maps, described impersonally in Crocker’s plan for Astonia as: ‘Night 5/6 September. Bombing of the harbour area.’

Those two squares denoted residential areas in the lower town and the city centre around the Town Hall, in the cellars of which, reinforced by wooden beams supporting the ceiling, Pierre Courant and his team had taken shelter, knowing from experience that the interval between the dropping of the TIs and the first bombs was too short for them to reach a bunker. At 18.05hrs they though their end had come. In fact, time did literally stop when the hands of the Town Hall clock stuck as a memorial to the raid.

For two whole hours, the firing of the German flak - rendered less intense than in previous raids by the prior removal of many 88s to the perimeter for use as anti-tank guns - the shriek of falling bombs, the noise of the explosions, the shock waves and crash of falling masonry stopped thought on the ground - or, rather, below it, where the civilian population huddled together in the cellars, communal shelters and slit trenches dug in their gardens. The last noise many of them heard was the dopplered scream of the bomb that hit their home and the crash of the entire building falling in and burying those still alive in the cellars, together with the corpses of their neighbours and families.

A few people more courageous or more desperate than the others managed to scramble through holes leading into neighbouring cellars and climbed up to the open air in the brief intervals between waves of bombers. Under a sky turned dark by clouds of smoke and dust from the explosions billowing hundreds of feet into the air, they ran desperately through streets littered with broken glass, dodging between huge masses of unrecognisable smoking fallen masonry, hardly able to breathe for smoke as incendiary bombs set fire to buildings.

© Douglas Boyd 2019, 'Normandy's Nightmare War: The French Experience of Nazi Occupation and Allied Bombing 1940-45 '. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd. NB The above images are not from this volume.

Affiliate Links

Recently on World War II Today ...

Miraculously, two nineteen-year-old sergeants survived under the pile of bodies. William A. Adams, the Nose gunner, and Sidney Eugene Brown, the Tail gunner, were both covered in severe bruising and lacerations. When another air raid siren went off they took their opportunity to escape

The rest of us had M-1’s. All of us fired so many times our barrels warped. In this little town, under a garage, was a cold storage tunnel. Someone had stacked ammo, grenades, cigarettes and candy by the case. So we had plenty of ammo, including Paul’s sub-machine gun ammo.

Maybe in the next war the French will fight longer then 6 weeks before they surrender. Or they will leave war zones before it's too late. Either way they made their decisions and had to live with the results. The French declared war on the Germans, but it's everyone else's fault. How ''republican'' of the French.