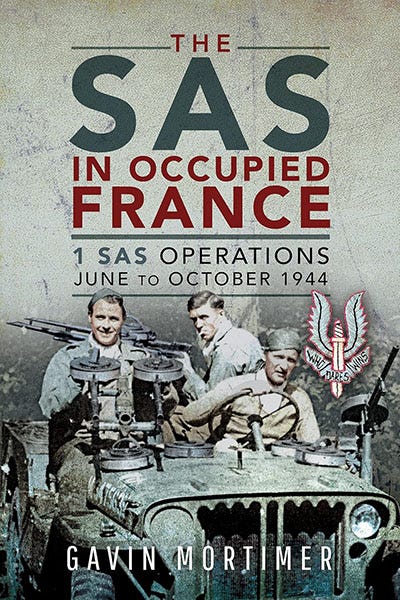

'The SAS in Occupied France'

An account of the 'behind the lines' raiding parties that used machine guns mounted on jeeps to attack German troops

Gavin Mortimer has written a series of accounts of different Special Forces units and their operations during the war. The SAS in Occupied France: 1 SAS Operations, June to October 1944 draws on a wide range of previously unpublished interviews with SAS members to describe their activities in northern and central France after the invasion. The SAS mounted several different operations to support the French Maquis and also made their own direct attacks on German troops.

The SAS squadrons concealed themselves deep inside French forests and largely avoided German attempts to hunt them down. This book also serves as a guidebook for those wanting to follow in their footsteps. The locations of their camps and the graves and memorials to the men who died lie far from the usual tourist trails.

The following excerpt covers Operation Gain, launched on 13th June:

After the briefing, the officers returned to their men and prepared to depart. Each man, recorded Riding, was permitted to carry 401b of personal kit. This comprised: two sets underwear; two shirts; one suit battle-dress; one jumping jacket; steel helmet; sleeping bag; map case; web belt; pistol; water bottle; compass and torch. Additionally, the soldiers carried seven 24-hour ration packs, and Watson and Riding were given £130 in French notes, large-scale maps and a wireless set, code book and decoding sheet printed on thin silk.

In the evening of 13 June six operational parties assembled at Fairford ready to go, the nerves of every man taut at the prospect of parachuting deep inside enemy territory. But events conspired to drastically reduce the number of SAS soldiers who actually landed in France in the early hours of 14 June. 'One aircraft, containing Major Fenwick, SSM Almonds and party, managed to remove the end of its wing while taxiing out of its bay and decided not to go,' stated a report. 'One aircraft (Capt. Garstin and Lt Wiehe) failed to find its DZ; on the way back it ran into flak. One engine failed and the pilot had to jettison all his containers in the Channel and to make a forced landing on the south coast. No one was hurt.'

In the end only the aircraft containing the sticks of Cecil Riding and Jimmy Watson deposited its cargo without a hitch. They were met as planned by some Maquis and led a few hundred metres north where they took refuge in a small copse. 'The French really worked miracles that night because in the space of an hour they had ourselves, our kit bags and parachutes safely cached in a small copse near the dropping-zone,' wrote Riding. 'We had to work very hard from 2.30am until 5.00am concealing the containers, which had dropped rather awkwardly between 1/2 and 1 mile away. When we got into the copse at 5 o'clock most of the boys turned in. Jimmy Watson and I agreed to wait till daybreak to see if we should be discovered.'

Watson and Riding swiftly developed a deep respect and admiration for the local people. 'The French were very glad to see us and gave invaluable help,' wrote Watson in his operational report, while Riding stated that: 'The whole time we stayed behind the lines the work of resistance elements was magnificent. On all occasions they cordoned our DZs, and went to no end of trouble to hide our containers and on no occasions were the containers tampered with.' In addition, villagers supplied the British with bread, milk and eggs, and some individuals took great personal risks to help the soldiers. A mechanic in the village of Nancray-sur-Rimarde, for example, regularly repaired the SAS jeeps, while the station-master at Nibelle kept them abreast of the running of German munitions trams along his single-track line.

Their experience with the Maquis was less agreeable. 'On the whole they were little better than gangs of terrorists and brigands,' wrote Riding. Watson wasnt quite as critical, describing some of them as 'shady characters', adding that their principal shortcoming was poor organisation caused by 'too many chiefs'.

In the decades since the war the 'Maquis' and the 'Resistance' have become interchangeable but it is interesting to note that Riding and Watson made a clear distinction. The Resistance, unarmed and unaggressive towards the Germans, were men and women whose lives outwardly had changed little during the Occupation. They lived at home and went to work as normal, but they 'did their bit' whenever possible, such as supplying food to SAS soldiers or sheltering shot-down airmen. The Maquis were armed, often political and lived in the forest. Their raison d'etre was to expel the enemy through force and punish those of their compatriots they considered disloyal.

The two most influential Maquis groups in the 35,000 hectares of the Orleans forest were Lorris to the south and Chambon in the north, both of which took their names from villages. Like other Maquis across France, their numbers were small prior to D-Day. Maquis Lorris, for example, had about thirty men when the SAS parachuted into the region in June; two months later there were 600, and it was these Johnny-come-latelys who were the 'brigands' referred to by Riding, men with questionable motives and dubious morals.

With such a surge in numbers in a short space of time it was inevitable that the two most prominent Maquis leaders, Marc O'Neill and Roger Giry, both veterans of the battle for France in 1940, struggled to keep all their men on a tight leash. O'Neill in particular earned the respect of the SAS. Despite his surname he was a pure Frenchman, the son of a general and grandson of an admiral, and one of the Resistants de la premiere heure in France, having helped establish a network in Paris in 1941.

On 17 June Lieutenant Leslie Bateman and his stick arrived by parachute, landing on a DZ approximately 20 miles (32km) south of Pithiviers and just to the west of the village of Vitry-aux-Loges. For twenty-four hours they laid up in a small wood near the DZ until they established contact with Major Fenwick and his six-strong HQ section, who had dropped on 16 June.

Joining forces, the SAS blew the Orleans-Pithiviers railway line on 20 June and continued to sabotage railways for the rest of the month. One of the SAS soldiers was Vic Long, a 20-year-old from Northern Ireland, who had volunteered for the regiment four months earlier. 'My drop into France was my first taste of action, and my first actual time was the Orleans to Pithiviers railway line,' he remembered. 'That went quite smoothly, although it was 25 miles away, and it was a five-night trip. The trouble at night was dogs, not Germans. You went through the village, and just as you got on the outskirts, you heard this yapping, and then windows opened. You remained still, the window closed, you'd go on another 100 yards, and then another dog starts yapping. But there weren't many Germans around at night.'

Further north, Riding and Watson carried out similar operations on the lines between Malesherbes and La Chapelle la Reine, and Fontainebleau and Nemours. It wasn't until Fenwick sent word by letter to Riding in late June that D Squadron assembled en masse in tire forest of Orleans, a camp estab lished by Fenwick between the villages of Nibelle and Vitry-aux-Loges.

Fenwick was troubled by what confronted him in the forest of Orleans. Despite its size, the forest offered only limited protection for his men. It wasn't (and isn't) a wild, untamed forest like those in the Morvan; it is a neat and tidy forest, criss-crossed with numerous tracks and paths, allowing ease of access for anyone on foot or in a vehicle. The terrain is relatively flat, affording good visibility for reconnaissance aircraft, and making concealment a challenge for any guerrilla force. Then there was tire question of the Maquis and their burgeoning numbers. 'We didn't really allow the Maquis into our camp because Fenwick said you couldn't trust them,' recalled Vic Long, a member of Bateman's section.

The first jeeps were dropped not long after the squadron had reunited and they were swiftly put to use. 'Various local sorties were made,' wrote Lieutenant Watson. 'On one operation in a jeep two German sentries were attacked ... and on the same night a road patrol at Estony was attacked. A railway train was burned and about thirty wagons destroyed. An extremely large locomotive was destroyed in its shed at Beaune and the shed severely damaged.'

In early July Riding and Watson drove their sections to the forest of Fontainebleau, around 35 miles (55km) north of Fenwick's camp, and set up base. A couple of railway lines were blown and, wrote Watson, a 'German officer was killed near our camp when the Germans were searching a wood in which we were presumed by them to be'.

The German had been shot by Sergeant Frank Dunkley and Trooper John Ion, but he was just one of a large force that had been sent to the area to flush out the enemy lurking within the forest. According to Riding, the local mayor may have been responsible for tipping off the Germans, and they would probably have been caught had it not been for Lance Corporal Alain Alibert, the Frenchman attached to D Squadron as an interpreter. On meeting the mayor, Alibert had sensed a shiftiness in his compatriot that eluded the British, and when the mayor agreed to deliver some food to the SAS camp, Alibert deliberately misled the mayor about its exact location. The 200 Germans who descended on the forest arrived at the wrong spot, and Riding and his men were able to escape and return to the forest of Orleans.

There, the fifty-eight men of D Squadron settled into a routine. 'We went out in small groups, between two and four men usually,' recalled Vic Long. 'A scheme [to blow a railway line] would last four or five days and when we returned to camp there wouldn't be many people around. We'd rest for a while, more would return, and then we'd go off again, and that's the way it went.'

© Gavin Mortimer 2020, 'The SAS in Occupied France: 1 SAS Operations, June to October 1944'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd.

Affiliate Links

Recently on World War II Today ...

If only for a short while, the terrible memories of the days of retreat and death slipped away, the years we endured together, the tears over those who passed away - all vanished in this moment of common triumph and joy!

We have lost about 97,000 men, including 2,360 officers - which means an average loss of 2,500 to 3,000 men per day - and we have received until now 10,000 men as replacements …