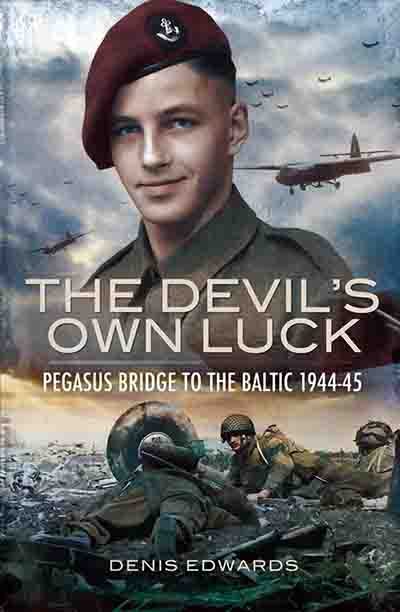

'The Devil's Own Luck'

An infantryman's vivid account of life on the front line in the Normandy beachhead - as experienced eighty years ago this week

Denis Edwards was a member of D-Company, Oxfordshire, and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, which landed by glider to seize ‘Pegasus Bridge’ in the first hour of D-Day. His platoon commander, Den Brotheridge, was one of the first men killed by enemy action on D-Day. Edward’s The Devil’s Own Luck, begins with a rare first-person account of the planning and execution of this action.

However, defying the odds, Edwards not only survived the Normandy campaign but also later engagements in Belgium (part of reinforcements rushed into the Ardennes during the ‘Battle of the Bulge’) and Germany. Throughout it all, he was keeping a detailed diary - in the form of notes which he kept concealed in his trench most of the time. After the war, he published these privately - but there was such interest in them that he was encouraged to rewrite them more fully.

This is an almost unique infantryman’s day-by-day account of life on or near the front line in the bocage of Normandy. Of the 180 men who arrived by glider on D-Day, only 40 returned to camp when they eventually returned to England in September. This diary chronicles the circumstances of that dreadful rate of attrition:

D + 8 - Chateau St. Come - Wednesday, 14 June

The day began with the normal stand to, followed by heavy and accurate shelling and mortaring from the enemy. Soon after breakfast I went out with an officer who led a small recce around the hedgerows to the front. He wanted to see the area and plot possible routes from which an attack might come, in particular the route along which tanks and self-propelled 88s might approach our positions.

German snipers were still infesting the area and taking a fair toll of men that we could ill afford to lose. To discourage their activities we snipers were sent forward in small groups to find a secluded spot from where we could watch the taller trees in which we guessed the enemy snipers would be located.

When a sniper fired, a telltale wisp of smoke could be seen. His position would then be given a real pasting, but they seldom worked alone, so that when we hit one, another would fire at us, so it was a case of firing and quickly moving to another location. Sometimes it was a matter of hurling a smoke grenade or two to cover our move. Using smoke was often a problem, however, because it worried Jerry, who took it as a prelude to an attack, and he would usually retaliate by mortaring and shelling the whole area.

In scouting around the deep ditches we came across many dead Germans and cattle. It certainly looked as though we had suffered heavy casualties, but Jerry had fared even worse.

Upon our return to Company lines we were delighted to find that a fresh supply of rations had arrived and, with them, a good supply of cigarettes, each of us receiving a tin of fifty.

The new trenches having been completed to the officers’ satisfaction, we hoped that we might get some time off to relax and get in some badly-needed sleep. We had been getting in little more than the odd hour or two at a time since we had landed in Normandy.

This was not to be the case, for, with the rations, we also received a large quantity of Dannert barbed wire which was heavy and had to be manhandled some thirty or forty yards out in front of the forward trenches. The wire was in large-diameter rolls which were pulled out concertina fashion to make a high spiral barricade. It was strung out across the entire front, with two rows of the coiled wire topped by a third, and the whole then wired together to form an impressive defensive screen. Although of little effect against tanks, it was difficult for ground troops to get through it, as we had painfully learned during training.

We didn’t object too much to this extra chore since it meant that if Jerry put in an attack his stick grenades could not easily reach our trenches from the far side of the wire.

When the smoke cleared all that was left of the mine-laying team and their truck was a very large hole in the ground.

In the evening a deafening explosion occurred to our rear. It was the result of a very unfortunate accident. To prevent tanks from smashing through our outer wire defences, the Regimental Pioneer Platoon had been instructed to lay an outer minefield.

The Pioneers had driven up in a large truck and began unloading the boxes of ready-primed mines and stacking them in a neat pile. Some of the lads were inside the truck doing the unloading while the others stood around waiting for the job to be completed. Apparently, assuming that all the boxes had been off-loaded, one of the men in the truck found two or three loose mines, which he placed on top of the pile of boxes. Unfortunately his mate had lifted the last box and, without looking, dropped it down on top of the pile. The loose mines exploded and detonated the whole pile. When the smoke cleared all that was left of the mine-laying team and their truck was a very large hole in the ground. This sudden enormous explosion panicked Jerry who immediately put down a heavy stonk, which ended what had otherwise been a comparatively quiet day.

...

D + 13 - Chateau St. Come - Monday, 19 June

In the dawn stonk the Company Sergeant Major was killed when a shell exploded near his trench and detonated his Gammon Antitank bombs. These bloody awful things were standard issue for us all and we hated them. They consisted of a sort of grenade or bomb, which was sticky and had a handle, resembling a large toffee apple. It was protected by a thin metal cover that was discarded when the bomb was about to be used. The bombs were highly sensitive and exploded with little encouragement. Standing orders were that these should be kept in every trench. If tanks overran us, the required procedure was to reach up and stick a bomb on the thin underside of the tank as it passed overhead.

From fear of the sensitivity of these infernal things, born of past experience with them, most of us dug a shallow hole within arm’s reach of the trench and placed the bombs there. If tanks came our way we could grab a bomb or two before they arrived. The only occasions that we took them into the trench were when the officers came round on a tour of inspection! Since the CSM was a stickler for discipline and orders, he probably kept his bombs with him inside his trench, and when an enemy shell exploded nearby it set them off.

The same explosion that detonated the bombs that killed the CSM also wounded the Company Commander. He was in an adjoining trench and was hit by shrapnel. He was taken to the Regimental Aid Post where the shrapnel was removed and he was patched up and, very courageously, insisted on returning to the Company, when most would have accepted such a wound as a sure ticket back to Blighty!

It rained heavily throughout the day and for some strange reason two platoons of ‘B’ Company were ordered to launch an attack upon nearby enemy positions. This was a very unusual event as we were normally holding a defensive line and none of us could fathom what was going on. Perhaps someone thought that if Jerry were as miserable as we were he would not be alert. He was, however, very wide-awake and ‘B’ Company stirred up a viper’s nest and were reported to be in deep trouble. We were ordered from our trenches and told that we were to put in a counter-attack to extricate ‘B’ Company.

Moaning Minnies were designed to plaster a large area with shrapnel as a result of a single firing, since they launched all six missiles simultaneously.

In pouring rain and soaked to the skin, we were none too happy when told that ‘B’ Company had pulled back and we were now not needed. While it was reported that about a dozen Germans had been killed, ‘B’ Company Commander and five others were wounded and six were missing, and the Commander of ‘S’ Company, which was really an HQ Unit, had to take over the command of ‘B’ Company.

Jerry obviously assumed that ‘B’ Company’s foray was the prelude to an all-out attack and immediately began plastering the entire front with artillery, mortars and ‘Moaning Minnies’. The latter was a kind of rocket mortar, fired from a 6-barrelled launcher called a Nebelwerfer by the Germans. It was mounted on a light gun carriage that was towed by a truck or a half-track. The projectile could be described as being somewhat like a six-foot length of drainpipe filled with high explosives and scrap metal and stopped up at the end.

Moaning Minnies were designed to plaster a large area with shrapnel as a result of a single firing, since they launched all six missiles simultaneously. Because of their shape, instead of swishing through the air like the streamlined shells and rounded mortar bombs, the missiles went up to a high altitude and then came screaming down to earth with a very characteristic noise, exploding on impact with a fearsome crash that shook the surrounding ground.

They had no accuracy and the six projectiles tended to spread out over a wide area. Although their explosive power could be devastating, they did little harm to those in well-dug trenches, unless they scored a direct hit, but the most notable feature about them was the blood-curdling noise that they made, screaming down from on high with a noise like a pack of wolves. When I first heard them they put the fear of God into me.

If it was the Battalion Commanding Officer who initiated ‘B’ Company’s abortive attack it most certainly backfired on him. Although Battalion HQ was behind the front line, Jerry may have thought that there were troops massing in that area ready to be launched into battle, so when he retaliated much of what he sent over was aimed at, and landed on or around, Battalion HQ. Several of the Battalion’s longest-serving men were killed or wounded, including the Quartermaster.

Also killed in the same bombardment was Sergeant Major Johnny Crew who had been out to the front to observe the attack and was returning to report to HQ. He was caught in the open on his way back when the first batch of Moaning Minnies came down. He was my first drill sergeant when I joined up in March, 1941, and a long-serving member of the Regiment.

Johnny had been sitting at the side of the road as we moved forward to put in our counter-attack. I said something about what a bloody awful day it was to be putting in attacks and he replied with something like, “you bloody lot from ‘D’ Company are always moaning and complaining about something or other”. This remark was very characteristic. Other units in the Battalion were perhaps a little envious that ‘D’ Company had been selected for the bridge job and ‘tongue-in-cheek’ cynical remarks such as this were just part of the everyday banter.

D + 14 - Chateau St. Come - Tuesday, 20 June

The bombardment of the previous evening continued throughout the night and at dawn it increased to a crescendo. Among the several casualties was the newly appointed Commander of ‘B’ Company, transferred from ‘S’ Company only the day before. He was killed on his early morning round while making himself known to the lads in his new command, and our Company Second-in-Command, and my platoon commander, Captain Priday, then took over ‘B’ Company.

It continued to rain heavily throughout the day, but we were now all so wet that we were past caring. Then came the good news that we were to move back into a Rest Area at Le Mesnil, a mile or so south-west from our present position, but by no means a mile away from the front line. The Devons, or ‘The Swedes’ as we called them, arrived to take over our positions.

Our new location was about 400 yards behind the front line between the two forward Battalions, the Devons and the Royal Ulster Rifles, known to us as the ‘Paddies’.

To the extent that we no longer had to watch the front or go out to the Listening Posts, Le Mesnil could be called a Rest Area. On the other hand it was within the general area where supplies were delivered, and so it was a prime target for enemy bombardment, and quiet it most certainly was not.

As always, having moved to a new position, our first job was to dig new trenches.

© Denis Edwards 1999, 2001, 2005, 'The Devils Own Luck'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd