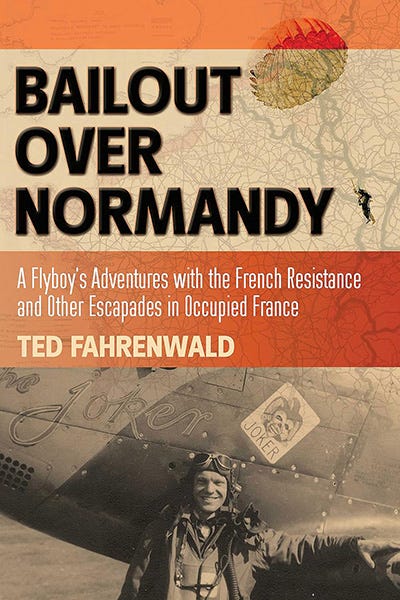

'Bailout Over Normandy'

Two days after D-Day a Mustang pilot describes how the 352nd Fighter Squadron deal with German transport in France ... but then things go wrong

Soon after he returned from the war Ted Fahrenwald set down his experiences as a 22-year-old P-51 Mustang pilot with the USAAF based in Britain. It was a fresh recollection of a series of remarkable adventures, written with the verve and style of an aspiring journalist. And then he put the manuscript to one side.

Only discovered by his daughter after his death in 2004 it was subsequently published as Bailout Over Normandy: A Flyboy’s Adventures with the French Resistance and Other Escapades in Occupied France. This is much more than an aviation memoir, or an escape and evasion memoir. It brings to life the outlook of a whole swashbuckling generation of young men - and the determination of one particularly adventurous individual.

Somewhere west of Paris we let down through the stuff and throttled back, cruising at a thousand feet, and our morning hunt was on.

In the following excerpt, Fahrenwald describes his fateful 100th combat mission:

So I drifted over to the booze locker to refuel my silver flask with a full charge of Channel Oil, and while I was at it, I took a quick nip. I stuffed a half-carton of cigarettes into my flying suit and announced to the motley crew that nothing mattered now: I was ready for whatever cards I might be dealt. Despite the gay line of chatter, I still thought it to be a helluva night for getting over the hump.

I wandered toward my ship, feeling the rain on my face and sniffing the soggy night wind and not giving much of a damn for anything. Good Sergeant German was slumped in the cockpit, snoring lustily. I pounded on the canopy until he came crawling out guiltily, and I swapped places with him. Came the time and I wound ‘er up, but that merlin engine wouldn’t kick over: the prop ground around and around and I thought, while mentally rubbing my hands together: “Ahhhh . . . Kismet! maybe the bastard will never start, I hope!” But my overly expert crew chief, blast his eyes, coaxed fire into the engine with a hot-shot from a handy battery cart, and the flames boiled back from the stacks. I taxied fast to catch up with the squadron and slid into position. And we poured on the coal and were airborne, four abreast in nice tight formation.

The tight sixteen-ship squadron arrowed up through low scud clouds into a dense and turbulent overcast. On top at ten thousand in the predawn light, the cloud scenery was desolate and bleak and as cold-looking as Little America. We slid out into a loose, line-abreast formation. Sixteen ships, and each little mustang looked sleek and dangerous and mean, and we were doing a thousand miles an hour as we streaked along through jagged cloud valleys, clipping hummocks and tufts and pulling up and over turbulent cloud hills.

Somewhere west of Paris we let down through the stuff and throttled back, cruising at a thousand feet, and our morning hunt was on. A loose formation, with every pilot straining his eyes in the faint dawn light, searching for targets along the roads and in the forests: mustangs weaving and rolling and occasionally skidding gently away from the showers of tracers that would lob up from hidden gun emplacements.

The weather in France was excellent, with a thin overcast at 4,000 feet, and when the brilliant edge of the sun peeped up, the countryside was rosy and objects on the ground cast long, clean shadows. And it was just a moment after sunrise when we hit the jackpot: a long column of thirty or forty trucks crawling around the right-angle turn of a gravel road, quite obviously headed for the safety of a large patch of forest a mile from their present position.

Spaced evenly, rolling slowly, this was a target of rare quality. One of the boys, whooping bloodthirstily into his microphone, peeled off to lay a pair of bombs directly in front of the lead truck, which obligingly burst into flames. The column was stopped dead.

Cold turkey, it was, and the radio livened up with savage cries. Taking interval, we raced into a big Lufbery circle just below the overcast, and one by one our ships rolled over into their dive-bomb runs. I watched the passes and saw the strikes, and they were effective. My turn now, and a deliberate approach panned out nicely. I chandelled, kicking the tail aside so I could observe my hits.

I felt mean and ornery, hungry and tired, and I hated the lousy guts of the whole damned Wehrmacht.

A dandy disaster below! trucks afire, long parallel banners of black smoke drifting across the fields, and the road all shot to hell with bomb craters. Now some of the boys were down on the deck beating things up with machine guns, and the traffic pattern was out of this world, with mustangs streaking in fast from every point of the compass, tracers crisscrossing, ships chandelling up all over the sky and at all angles. Fighter pilots huddled in a smoky old barroom couldn’t have dreamed up a tastier target than this!

Having no particular desire to plunge into that reckless rat-race, I went shopping around the perimeter of the target area. A couple of miles back down the road, I spotted six or eight heavy trucks, untouched and half-hidden by low hedges. With a waggle of wings, I gave my wingman the word and we pounced down onto our own private shooting gallery, coming down in trail for our first pass.

My first squirt smothered the rear of the last truck with a dancing, flickering mess of incendiary strikes. Pulling out of my dive I held down the trigger, laddering my fire away the hell and gone up the road, getting a few strikes on assorted vehicles and spraying the ditches liberally. With an evasive, skidding wingover we went in broadside to the column, flying nearly abreast, each flaming our targets. My guns seemed to be perfectly harmonized, coming to a sharp focus some three hundred yards ahead of my ship; and any target caught in the focal point was automatically a dead duck.

I spotted one truck parked smack against the wall of a small farmhouse at a crook of the road and managed to get a short burst into the truck without seeing too many strikes on the poor Frenchman’s house - never thinking that if the truck burned, the old homestead would go up along with it.

Streams of tracers were pestering me now, but about the only chance the Jerries had of scoring was during the six or eight seconds of accurate, coordinated flying necessary when actually firing my guns: at all other moments, during the approach, pullout, and getaway, slipping and skidding evasive action was in order. I felt mean and ornery, hungry and tired, and I hated the lousy guts of the whole damned Wehrmacht. A roaring lust for destruction was with me now, but I was about fresh out of ammunition - and I wanted a bit to travel on. But untouched below sat the great granddaddy of all Jerry trucks, so I thought I’d better shoot it up, just a little.

Barreling in, I concentrated on one long and accurate squirt, and a devastating stream of 50s ripped into my target. I held down the trigger until the range was point blank and the Joker was clipping the weeds with her prop. At the last possible split second I jerked back the stick. Whereupon my luck ran out.

As I crossed over the truck, the son of a bitch blew up - it having been packing an overload of ammunition. A mighty thud and a mightier surge skyward, combined with what sounded to my ear like a whole belt of machine-gun slugs pounding into the belly of my ship. A split second later I found myself to be some five hundred feet up, inverted and climbing. Half-rolling, I kept going upstairs, using my initial velocity of some 375 mph to gain a lot of altitude in a hurry. Leveling out at 4,000 feet, on course for England, I took hasty inventory.

I had control of the ship and the engine instruments were normal. My wings were bent and beat up a bit: the skin was wrinkled and a lot of odds and ends from the disintegrating truck had holed through. There was a smoke trail behind me. I thought about how Pappy had gotten it the day before, in exactly the same circumstances, and I felt lucky. My wingman slid in alongside to radio that he’d stick with me on the way home.

Having been preoccupied in cleaning my fingernails during briefing, I didn’t know just where in the hell I might be, but figured that a course of due north would be as good as any. For a minute I cruised smoothly in that direction. The Jekyll-Hyde transformation induced by every good strafing attack was fading, and now all I wanted out of life was to be back at the field, to have a bit of breakfast, and to then log a little solo sacktime.

I was glad that I’d not been forced to bail out in the target area, for we’d strafed unmercifully and I didn’t suppose that the Jerries remaining alive on the ground would have been inclined toward kindly treatment of fighter pilots. But now the green forests and meadows of Normandy were sliding along below, very nicely. And as I was patting myself on the back, my engine instruments began to shout bad news right in my face.

That vital little coolant-temperature needle began a slow crawl across its dial toward the red danger line. I throttled back to minimum cruise and opened the oil and coolant shutters. The needle dropped back to normal temperature, then started back up again: whereupon I eliminated from my mind all thoughts of England and steered more westerly, figuring to try for friendly territory on the beachhead. The engine got hotter and nothing I could do would bring her back to normal.

The roughness of the engine could be felt first in the stick, and then the whole ship was trembling violently. I was in bad trouble, and my wingman had to circle and “ess” in order to stay back with me. I tried like hell to keep her going - at least long enough to reach the Channel- now figuring to make it that far and then to sit in my fancy rubber dinghy while waiting for Air-Sea Rescue to fish me out. But the engine commenced to run very roughly, and quickly rougher, and I jazzed the controls in a frantic effort to find a smooth spot. The Joker was pounding violently now, with airspeed dropping away rapidly: 140 mph and 3,500 feet indicated altitude, and the ship was just staggering around the sky.

Then the whole damned engine froze up and the tired old prop, with ironic finality, stuck up in front of me like a v-for-victory symbol. Streaming back from the cowl, white smoke turning to black with gusts of flame flashing back on either side of the cockpit. Fearing a cockpit explosion, I snapped the oxygen mask over my face, flipped my goggles down over my eyes, unbuckled the safety belt, cleared myself from the tangle of shoulder harness, and retrieved my cigarettes from their slot alongside the gunsight - all done in a moment.

A glance at the ground, and France assumed an extremely personal aspect. I pushed the mike button and yelped out a fond farewell to the squadron in general. I hated to get out into the long tongues of smoke and those wicked little jabs of flame, but I had to make tracks in a hurry. Without debate, and automatically following a long-prepared plan of action, I pulled up to a stall, jettisoned the canopy, and jumped.

I was damned near clear of the wing when the Joker snapped off on the left wing into a quick spin, which treacherous action on the part of my aircraft scooped me neatly back into the cockpit. My right leg was wedged well up under the instrument panel while the rest of my carcass dangled outside, streamlined back alongside the fuselage, and I caught a flash of green trees coming up fast.

With what seemed to require no effort, I hoisted myself back into the flame-filled cockpit and yanked my leg free. In a very few seconds I’d either be dead or alive and I knew it, but time gave me a break and paused where it was - each fractional second seeming to allow minutes in which to think and act. I recall figuring angles and judging odds and at the same time feeling interest in one’s ability to think analytically under the pressure of such intricate circumstances. Arriving at a final plan, and with no indecision, I crouched on the bucket seat and launched a desperate leap straight upwards from the ship: on up and over the top of the cockpit and over the tail. And upon seeing the vertical fin slice past beneath me, extreme elation was experienced.

Falling head down, I could see my ship close below, silver and blue against the dark forest, spinning fast, with a trail of smoke behind her. My body had too great a velocity for a comfortable ‘chute opening, but I was low to the ground and I gave the old ripcord a mighty tug and felt the beginning of a powerful jolt.

© Ted Fahrenwald 2012 Edited by Madelaine Fahrenwald. Bailout Over Normandy: A Flyboy’s Adventures with the French Resistance and Other Escapades in Occupied France. Reproduced courtesy of Casemate Publishers.