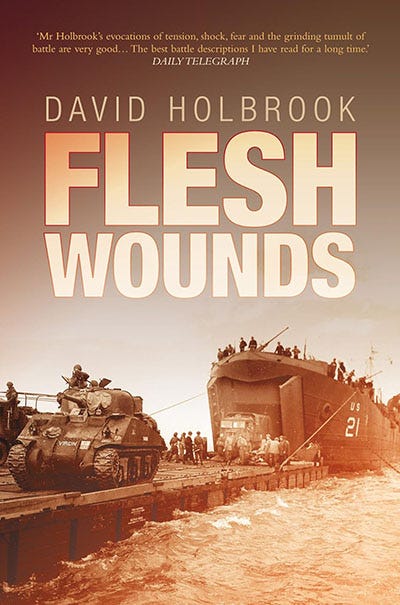

'Flesh Wounds'

The experience of landing in a Sherman tank on the beaches of Normandy, an excerpt from an 'autobiographical novel'

It took David Holbrook seventeen years before he was ready to write about his experiences in the war. He then found himself more comfortable writing about his feelings from the perspective of a third person, ‘Paul’. Nevertheless, the process appears to have been a great unburdening - he describes writing 18,000 words in one day when he recounted his experiences on D-Day.

Flesh Wounds was eventually published in 1966 to considerable acclaim. The following excerpt is just part of that long description of landing in a Sherman tank on D-Day:

Then the smoke cleared and he had a good view of the beach. Images came into sudden focus in the greenish oblong of glass. High up along the beach he saw a tank burning, and then, sud denly, under its dipped and useless gun, a row of dead beside it. The full dreadful sense of waste came flowing into his gorge, the first full flavour of machine warfare. There are moments, short moments, from which we never recover, and this few minutes up the beach was one of those for Paul, as it was for hundreds of thousands of men besides.

The loss of one's virginity takes only a little time, and leaves one forever changed - if happily, for life and love. But this first minutes' baptism of fire changed Paul's sensibility forever, for ever to be a little deadened. He tasted the full price of death, the abominableness of which human nature was capable, the immense destructivity of man, and the frail predicament by which in the midst of the apparent stability of life we are always in the instability of possible immediate obliteration. This is a truth with which we always live: war uncovers it mercilessly. The small mirror image of the voraciously burning tank with its luxuriously billowing black and red fire, and the row of baggy sack-like dead beneath it did this for him now.

After so many years of preoccupation with the care of an efficient machine a man comes to develop a pride and affection for the thing. Soldiers in an armoured regiment are proud of their fighting vehicles and deeply attached to them emotionally - cold, clumsy, uncomfortable mastodons as they are. The Paul Grimmers and Dowsetts had slept in them and under them, bivouacked with them in wild places, and driven them recklessly through scrub and forest. They had maintained them to a high pitch of efficiency, and had kept them clean and neatly stowed. They tended their tanks, so they might have confidence in them.

The machines became substitutes for home, with their stowed cooking stoves and their bulkhead stores of food and water. The steel walls of the Shermans had protected them from shellfire and bullets in exercises when live ammunition was used, and they expected them to protect them in war, the American mastodon mothers in whose bellies they lived. Each greenish steel dome with its armoured flanks was home for five men. Their tanks had private letters tucked behind the No. 19 set, as behind the clock on the mantelpiece at home and in handy places here and there the tank men kept their round tins of cigarettes and their bars of motoring chocolate.

It seemed hideously wrong that the mastodon mother herself could be destroyed: and so the first sight of a burning tank dislodged a fundamental security in the trooper's soul. Tanks burn in a way that has its own grotesque poignancy. The flames are explosively fierce and yet are tightly contained in the hollow steel shell: so, the smoke rushes out with tumbling fury.

The occupants, if they are not already torn to pieces by the penetrating armour-piercing shot, must be very quickly asphyxiated, then burned rapidly to cinders by the fierce flames of diesel oil and exploding cordite charges, rag ing through the hatches and the turret. From the turret black smoke alternating with intense flame thunders forth in a monstrous jet. But then from time to time the smoke is forced into huge expelled puffs by the exploding shells within. Each black puff, from the circular turret hatch becomes with grotesque perfection a rolling smoke ring. Such a smoke ring we associate with quiet reflective moments - old men showing their skill with a pipe in the chimney corner, to admiring children. The perfect black smoke ring shooting up from a burning tank suggested some grotesque devil's game in the thing, a derisory joke of the fiends, over dying men.

A burning tank, because of this, looked like a monster, a dying dragon, vomiting up the life within it in black gouts, and blowing aloft ghostly rings which mounted, curling in on themselves, high into the air. Beneath these sad signals, a red and white glower would roll in the eyes of the dead monster, the hatch holes, through which the crew had entered, never to emerge again. For there within, where once was chattering comradeship, offers of chocolate and tea, gossip and chaff, where the men had sat with their headphones on and worked with maps or preparing meals, was a tempestuous fire, the red hot or blackened steel.

Whenever he saw a tank burning, Paul felt impelled to gaze within to see what had become of the life that had once climbed in so actively. Yet no-one dared do so, until the cindery mass was cold, because of the violence of the explosions from the shell racks - even though shouts could be heard from the interior, when the first terrible clang came from the strike of steel on steel.

This appalling sight Paul saw in the first minutes on the beach, at one instant, through his periscope. The meaning of it began to sink in, as the bewildering hours of his baptism of fire lengthened, generating in him his first taste of battle shock. It was not one of his regiment's machines - 'A' and 'B' squadrons had come in scot-free earlier from their LCTs, and were driving inland. The burning tank was a thirty-ton Sherman tank belonging to the engineers who had cleared the beaches earlier. It was a 'Crab' tank, with flails - long steel arms in front sup porting a power-driven axle, on which hung chains. When the axle revolved the chains would beat the ground and explode anti-tank mines. It was dangerous work, as Paul knew.

The Wehrmacht knew about Crabs. Sometimes they would set a delayed fuse and attach the mine to a bomb, so arranged that this would explode under the tank, as soon as the beating chains struck a mine. He had learnt about such devilish contrivances, in the abstract, at courses on explosives. And he had passed over the phrase 'knocked out by anti-tank fire'. He had felt a little security in phrases such as 'covering fire' and 'defusing'.

But the first sight of the actuality had ripped the flimsy security from him. The massive steel turret of the Sherman was even dis located from the hull by the force of the impact from an 88 mm. armour-piercing shot, travelling at some 3,000 miles an hour. The shot had churned round inside the tank, rending up the men inside into shamble-fragments like the pile of choppings that is thrown in a heap in the butcher's shop for the scavenger or the glue factory. Five men had been mixed for an instant with ripped cordite charges, the smashed wireless set, spare clothing, tins of food, belts of ammuni tion. And now in a refining fire the pulverised mass of flesh and artefacts blew its death-signals into the air through the turret hole.

Fascinated and sick, Paul heaved at his lightly sealed hatch, and thrust it open. Dowsett, who was back in the turret hatch, also tense and grim, barked at him:

'Paul, I shall want that hatch down to traverse.'

'Thought I'd watch down here for obstacles.'

'Righto.'

But Paul really wanted to confront the reality of the death and waste, in the open air. The green periscopic image was still too much like a newsreel, or a dream; there was nothing yet for Dowsett to shoot at. He must quell his reeling sickness. He must look.

He put his head out. The Sherman Crab was not the only knocked-out tank. There were others, monsters which had lumbered to carry large charges to the concrete pill-boxes, tilted on their sides and blackened with fire, boiling out smoke. Their bundles of fasces lay in place, or were spilled about the beach. Half-tracks, armoured cars, self-propelled guns and engineer tanks lay about the sand too, tipped over or blown open, burning, reddened and blackened by fire, smoking and blazing, their tyres or fuel tanks on fire. Other machines had simply stopped in their course, sunk in sand, their great metal tracks broken on mines.

The surf drove up higher among them as the tide came in. But now he had his head out of his hull hatch and could see directly along the beach Paul was surprised at the rate things were moving. There were men and moving vehicles, congested and confused, but along the exits they poured steadily, in files and convoys, through the lanes marked with a jumble of tapes and flags, despite the broken machines and the dislocation. Here and there an outbreak of smoke, shouts and flung bodies marked a shell salvo: but this was a beachhead functioning briskly, with arms and men poured over the top ridge of the beach. The assault was well away from the water, the tripod-like beach defence obstacles, and the jumble of great wrecks. They were not to be stopped before they left the surf. Of course, they could still be driven back into the sea by a determined attack. But they were definitely on shore, and moving. Even so, he couldn't think clearly what movement inland would be like. They had thought of beaches so much that to get off the beach in the first minutes seemed something of a flop.

Paul's tank reached the dunes and shingle-bank at the top of the beach, beyond the end of the row of some seaside houses, on the easterly outskirts of Lion-sur-Mer, a few small pink and white villas. The houses on the shore seemed to have been evacuated by the Wehrmacht: there were no French people about. The villas had been boarded up and were broken by shellfire, but still stood hope fully gazing out to sea as seaside villas do. They had caught a good deal of blast and some direct hits. As the troops in their drab khaki swarmed past them they looked forlorn, the boarded windows broken up here and there, the roofs, the walls holed. But yet many stood erect still, with four walls and a roof, some even with the tele phone wires attached.

Paul was surprised that everything wasn't flattened. He'd seen a demonstration of the intensity of the gun and rocket barrage: from the thunderous drumming it seemed that nothing could survive such an obliterating cannonade, the cliffs alive with packed flame and smoke, bursts as thick as bushes in a copse. To the left such a barrage had fallen: there smashed houses burned, and the roads behind the beach were almost impassable with craters. But as they pulled out to the west they moved into comparatively untouched seaside: many of the little villas were still more or less intact, their white walls and red roofs shining, despite an odd hole here and there. The village of Lion-sur-Mer itself farther along had escaped bombardment, as there had been no landing directly in front of it. In the gleams of sun it looked almost gay, with barrage balloons aloft beyond it, giving the place something of a regatta air. Paul studied the foreign look of the place with satisfaction, the pretty coloured shutters at each window, the curly insulators on the telephone posts, the blue and white street name plates, and the gimcrack French provincial finish of the newer houses.

Certainly, this was not Littlehampton. As they climbed the track they reached their first road in enemy territory, a dusty torn strip behind the beach villas, with potholes in the asphalt, and stretches of loose aggregate. Dowsett and Paul were so anxious to reach the clear road that the tank nearly ran over a line of dead before they noticed.

'Driver halt!'

A beach officer with shell-shattered nerves, a drawn grey face under his hat, his battledress filthy with water, oil and smoke, waved at Dowsett.

'Don't stop! Don't stop!'

But even Dowsett couldn't drive, yet, over the bodies of English infantrymen and pioneers. The driver awkwardly backed in the dunes, as the men directing the traffic in the exit waved them on, cursing.

'Poor sods have had their bloody invasion!'

As they went past Paul studied his first war dead at close hand. They were statuesque, holding their postures stiffly, and so not crouched in relation to the earth as live men would be: there is no relaxation in the dead. Most seemed whole: it seemed an outrage that they could not get up and move on. There seemed nothing wrong with them: solid flesh in the thick cloth battledress. Most were khaki: two were grey-green enemy.

But then Paul noticed the subtle difference in the colour of their faces from live faces - a greyish white or pale blue-green tinge. And then the sack-like, stiffening posture, the clenched fists. Perhaps a patch of black blood at the ears, a brown stain at the corners of the mouth. He's gone. The mind and compassionate impulses recoiled, as they never did from a wounded man. Hopeless! One was impelled to rush to a wounded casualty, to foster life. But a corpse one left alone. One could even drive over a corpse.

Yet Dowsett could not. And as they passed close by the row Paul could see what had made the difference between live and dead: the odd line of holes punched in the cloth of their dress, that was all. Sometimes edged with black, sometimes with brown, these small holes, round, or large and jagged, marked apart the statuesque thing that was no longer a man, marked it apart from the living soldier. The wounded man was different: his cloth was urgently cut away for a field dressing to be applied. Living but disabled, he was the pitiable infant of the field, treated the more like a baby the nearer he was to death.

But once life was extinct the heavy object, the dead meat of a man, became a nuisance, both materially and to the mind. Whether enemy or 'own troops', it must be hidden, dumped: must be driven over, even, in need. But Dowsett jibbed, and Paul was glad.

After much slurring sideways in the heavy dune sand, among furious faces, grey with fear and fatigue, men shouting and waving, their Sherman tank tilted down on to the beach road behind the villas, and they nosed their way through the hawthorn hedges. They knew the lay of the fields behind Queen Green a little from the air photographs they had studied on the boat. The first objective was the Periers Ridge, already being violently contested.

Dowsett made for an orchard at a prearranged map reference, half a mile inland from the beach. The mint maps were in use: Paul's tank was on foreign earth, moving inland, with live ammunition in the breeches of the guns, and the rich Normandy countryside gleaming behind the crosswires in the gunner's telescope.

© David Holbrook 1966 & 2007, 'Flesh Wounds'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Sword Publishers Ltd