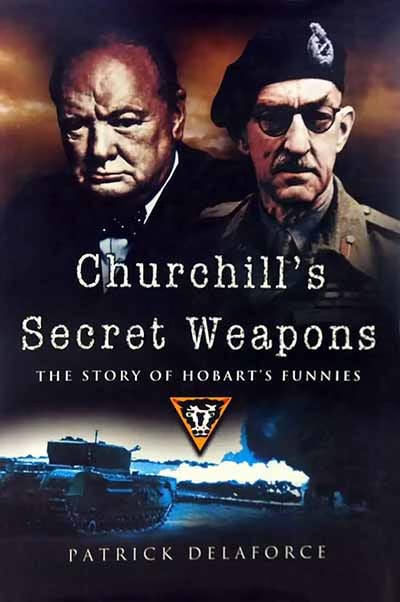

'Churchill's Secret Weapons'

The story of 'Hobart's Funnies', the specialist assault tanks used by the British on D-Day and through the campaign in Europe

On D-Day, the British were to deploy a variety of unusual tanks, each adapted to overcome different physical obstacles in the ‘Atlantic Wall’. The bloody debacle at Dieppe in 1942, when the bulk of the assault force was trapped in a hail of deadly fire while still on the beach, had given them a great incentive to think imaginatively about a new approach.

Churchill was to play a key role in promoting the new armoured vehicles that were developed as a consequence. Crucially he plucked the eccentric General Percy Hobart from an obscure command with the Home Guard and gave him responsibility for 79th Armoured Division. As an Engineer with an uncompromising outlook, Hobart was unpopular with many of his peers who came from completely different backgrounds. He was no more popular with most of the men under his command. Yet he did force through the development of a series of weapons that were unusually effective.

Patrick Delaforce, who served with 79th Armoured Division, gathered together a wide range of personal accounts about the development and use of these tanks in Churchill's Secret Weapons: The Story of Hobart's Funnies, first published in 1998. He takes the story from the early bleak days of late 1942, right through to the heart of Germany in May 1945.

This excerpt describes the early concept … and the experience of army service in a Churchill AVRE tank:

Winston Churchill was particularly involved in the concept of the AVRE (Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers). He had foreseen the need for engineers to be mounted in tanks for the breaching of sea defences; he had identified the need to utilize surplus Churchill tanks and his protege Millis Jefferis, by developing the Petard hollow-charge bombard, had produced the ideal weapon.

A Canadian officer, Leiutenant J.J. Donovan had, after the debacle at Dieppe put forward various ideas for protecting the sappers in the front line of fire. The Churchill tank, although slow and ponderous, was roomy, had tough defensive armour and side-access hatches in the track frames. Through these a demolition NCO from the crew of five could exit with General Wade charges, and place them in position against sea walls or whatever the object that needed to be demolished.

The bombard was fitted to Churchill Mark III or IV types. On the back of the tank could be placed either a huge brushwood paling fascine for filling in ditches, a Bobbin log ‘carpet’ for treacherous muddy ground or a small box girder bridge (SBG).

Other variants duly followed: a skid Bailey pulled or towed to span a 60-foot length; a mobile Bailey (pushed forward, disengaged and mounted by the AVRE, allowing the front half of the bridging to fall into place); and an armoured sledge to be towed behind an Ark (a turretless tank with a ramp), various mine-clearing devices, and many other useful or dangerous ‘extras’.

The main weapon, the Petard, carried a 26 lb charge within the outer casing (the Flying Dustbin) giving a gross weight of 40 lb. This could be fired up to a range of 230 yards but the most effective range was about 80. Practically any target of steel, brick or concrete could be destroyed. Later the long-range gun batteries at Cap Gris, in their huge bunkers, withstood a Petard attack.

...

Sapper Ian Isley of 16 Assault Squadron RE described his life and times with the AVREs.

“Sitting in a tin box for most of the time one doesn’t have much idea of what is going on around one. Certainly officers who attend the ‘O Groups’ are well informed of what is going to happen, or should happen. They in turn tell their tank commanders what will be their part of the action and some tank commanders tell their crew - but not all tank commanders bother to impart this information to their crews.

The wireless operator is reasonably well informed being on net to the outside world but the remainder of the crew arc in complete ignorance. The driver is told to advance and to steer left or right as required, the turret gunner and the front gunner wait to be told when to load and fire and the poor old demolition NCO sitting on the tool box behind the driver just has to sit there patiently listening to all the commander’s instructions over the intercom.

A few words on the life of an AVRE crew. It was very crowded inside that tin box — instead of a normal Churchill crew of five we carried six men - the demolition NCO already mentioned, the men in the turret, the commander, wireless operator and gunner, who had seats the size of dinner plates to sit on and as hard.

The front gunner in the hull had a lightly padded seat with a canvas sling type of back rest to support him and enable him to open his sliding hatch and lift up the 40 lb Flying Dustbin and load it.

The driver had a conventional seat but the position of the backrest was critical inasmuch as the clutch stop beneath the clutch pedal had to be hit ‘just so’ in order that a gear in the gear box could be slowed enough to enable him to change gear with the crash gear box. The gear box had four forward speeds and one reverse. One normally started in second gear and changed gear at exactly 1,500 revolutions - any other reading would result in a missed gear, a terrible noise from the gearbox and instant loss of steering - the tank had to constantly be in gear to be steered.

The noise in the tank, even with the headsets being worn, was indescribable. Unlike conventional tanks we had no track top rollers and the track was noisily dragged along channels each side of the hull.

Contrary to popular belief the interior of the tank was bitterly cold most of the time and it leaked like a sieve through the various hatches whenever it rained. The two large air intakes for the engine were located in the turret compartment and sucked in large quantities of air through every open orifice.

Every grain of dust and every rain drop within yards of the tank suddenly defied gravity and was drawn into the interior. In action, the driver had a thick armoured glass block to see through but when this was not in use the driver had an open rectangular porthole to see the way ahead. All the dust from the vehicle ahead and all the dust from the rotating tracks in front of the driver were sucked through this opening and no matter how good the goggles were, if the driver fell asleep without washing his eyes out, his eyelids and lashes were glued together on awakening.

My overriding memory of those days was the feeling of tremendous fatigue. At the end of a day we had to maintain the vehicle and carry out routine servicing tasks. When this was done we had to build whatever devices were needed for the next day. It could be putting a fascine together or building a short box girder bridge and winching it up or some task that was always in addition to the normal duties of a tank crew.

Sufficient sleep was our main concern and every opportunity was taken to catch up on our much-needed rest. It was not unusual to bed down in the early hours of the morning and be awakened four hours later to prepare for the events of the day ahead. If one was saddled with guard duty the hours of rest were even more curtailed.”

© Patrick Delaforce 1998, 2000, 2006, 'Churchill's Secret Weapons: The Story of Hobart's Funnies'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Swords Publishers Ltd

Very Ingenious. Q Branch could not have been more proud.