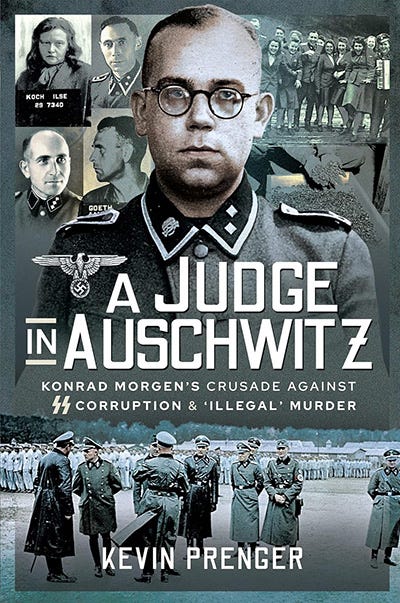

'A Judge in Auschwitz'

The remarkable account of SS Judge Konrad Morgen - whose role was to investigate the SS for corruption - of his guided tour of Auschwitz

The SS was in many respects a law unto itself. Its entire structure was separate from the rest of the German state. Yet this key Nazi organisation, responsible for some of the most appalling crimes in human history, was a disciplined force - with its own discipline code and means of policing its own ranks. This included its own investigating judges who reported to the highest-ranking Nazis.

One of these judges was Konrad Morgen. Bizarrely, given the scale of the crimes being collectively committed by the SS. Morgen was responsible for investigating individual members of the SS. In this role he got unprecedented access to SS facilities - including the extermination ‘camps’ at Buchenwald and Auschwitz. His post war evidence to the war crimes trials, mainly as a witness, was to provide a unique insight into the operation of these killing centres and the men who worked in them.

The following excerpt from A Judge in Auschwitz: Konrad Morgen's Crusade Against SS Corruption & 'Illegal' Murder is a summary of his guided tour of Auschwitz in the Autumn of 1943:

After Morgen and Hoss [the camp commandant] had made their acquaintance, an officer was allotted to him with orders to guide him through the camp. Subsequently they visited all important sections of the camp by car, including the extermination camp in Birkenau. During the Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt, Morgen reported extensively about this guided tour of the camp. He told that the tour started at the ‘beginning of the end’, the platform of Birkenau.

There the procedure when a new transport arrived was explained to him. The platform was ringed by guards and when the doors of the carriages were opened the Jews had to disembark and leave their baggage behind. Men and women were separated and rabbis and equally prominent Jewish persons ... were taken aside immediately’. According to his guide, it was ‘expected of these prominent persons to send as many post cards and letters as possible with greetings all over the world in order to obscure any suspicion that something gruesome was taking place here’. Such mail, preprinted postcards with soothing words, were actually sent, from the fictitious village of Waldsee to next of kin, to reassure those Jews still to be deported to the East.

After men and women had been separated they were asked if there were skilled people who could be useful to the industry connected to the camp. Those specialists, like engineers, technicians and such, were singled out while the rest were checked to see if they were fit for labour. Those who were and the skilled prisoners were marched off to the prison camp of Birkenau where in the course of time many would perish as a result of the deplorable living situation and the inhuman work conditions.

Prisoners unfit for labour, like children, the elderly, the sick, the disabled, immediately left for the gas chambers, most of them on foot, the more or less disabled by truck. Morgen’s guide told him that ‘when there was no time, no physician available or there were simply too many prisoners, the procedure was sometimes cut short: the arrivals were told, in polite words, that the camp was a few miles away and that those feeling too sick or too weak or for whom walking was too uncomfortable could make use of a vehicle already waiting for them. There was a stampede to get into the vehicles. Those who didn’t get in could march into the camp, while the others had unknowingly opted for death.’

After having seen the platform, Morgen and his guide visited Birkenau itself. ‘From the outside, nothing conspicuous could be seen either: large, somewhat crooked gates, with sentries,’ he recalled.

He was shown ‘Canada’, the part of the camp where the baggage of the deported Jews was collected and sorted to be sent to Germany to be reused. Morgen saw ‘from the last transports stacks of suitcases broken open, laundry, brief cases, but also complete dental equipment, shoemakers’ tools and medicine kits lying around. Obviously the so-called evacuees had actually assumed they would be resettled in the East, as they had been told and had prepared themselves accordingly.’ The department took its name from the large amount of stored goods, associated with the wealth and abundance of Canada.

In Birkenau, Morgen was also shown what he, as he said, had come to see: a crematory and a gas chamber. Based on the details he described he probably visited Krema II or III, two T-shaped crematories, one a mirror image of the other, built in 1943. In Frankfurt he gave a detailed description of what such a building looked like. ‘They were one storey spaces with gabled roofs that could just as well have been sheds or small workshops. Even the very wide and massive chimneys would not be noticed by lays as they were quite modest, they ended just above the roofs.’

At that moment there was no gassing in progress but he did see ‘a herd ... of Jewish inmates with their yellow star and their kapo carrying a long cudgel .... They, the kapos, continuously walked around them, yelling orders and catching every look. It crossed my mind they were behaving exactly like shepherds and their herds. I told my guide, he laughed about it and said: “they have been ordered to”.

The victims who were going to be killed had to be put at ease by the “brothers in faith”, acting as kapos.’ Kapos were instructed ‘not to beat the arrivals. An outbreak of panic had to be avoided. They should give them a little fear and respect, for the rest just be there and guide them to the location where the camp management wanted them.’

‘Where they wanted them’ was the gas chamber. Before entering this chamber, the victims were to undress in a room which, according to Morgen, was comparable to a dressing room in a gym. ‘There were simple wooden benches with racks for clothing and, conspicuously, each place was numbered, had a cloakroom number. It was also pointed out to the victims they had to watch their clothing, they should remember their number, everything aimed at keeping up the facade, literally until the last second, so as not to arouse even the slightest suspicion and let the victims walk unexpectedly into the trap.’

Morgen stated that he visited the gas chamber as well. The victims were guided there by ‘a large arrow pointing to a corridor with the short text: “to the showers” in six or seven languages. They were also told: you will undress, take a shower and be disinfected. The corridor led to various rooms without any furnishing: barren, empty, concrete floors.

Conspicuous and moreover unexplainable was a shaft of latticework in the centre of the room reaching up to the ceiling. I had no explanation for this until I was told that gas in crystalline form, Zyklon-B pellets, was dropped into the chamber through an aperture in the roof. Until that moment, the victims were completely ignorant, but then of course, it was too late.’

After the victims had been gassed, the corpses were taken to the ground floor in an elevator (the gas chambers of Krema II and III were located in the basement) and then to the crematory which was also shown to Morgen. He described it as ‘an enormous hall with the ovens at one end in a long row, with a flat floor; everything exhaled a businesslike, neutral and technical atmosphere. It was all shining like a mirror, polished, and some inmates dressed as mechanics were cleaning their equipment with robotlike movements. As for the rest, it was quiet and empty.’

Morgen recalled he had not seen a single SS man in the crematory. He would however very much like to see the SS men and get to know them, who are running and managing this whole system. Hence, a visit was paid the to the guards’ quarters in Birkenau. This visit made a shocking impression on Morgen. The housing was very different from what he was used to in military barracks which in general ‘were characterized in all armies of the world by a Spartan simplicity’.

While expecting a tidy room with a desk, posters and bunks, he entered a somewhat shadowy room’. ‘Ranged in a circle was a weird collection of benches. On these benches a few SS men lay, most of them without an officer’s rank, staring at infinity, their eyes glassy.’ Morgen had the impression ‘they must have consumed quite a lot of alcohol the previous night’. But what stunned him the most was ‘that instead of a desk, there was a large furnace in the room and four or five young girls were baking potato cookies.

They were obviously Jewish, very pretty, Oriental beauties, big breasted, sparkling eyes. They did not wear prison garb but normal, rather sexy civilian clothing. And they took those cookies to their pashas dozing on the benches, asking them if there was enough sugar on the cookies and feeding them.’

No one paid any attention to the visitors, even though Morgen’s guide was higher in rank than the others. ‘Nobody said a word and no one could be disturbed. And I could not believe my ears, these female inmates and the SS men were on first name terms. I must have looked quite astonishedly at my guide. He just shrugged his shoulders and said: “The men have a busy night under their belts. They have processed a few transports.” ... That also meant that during the night while I was travelling to Auschwitz by train, a few thousand people, a few trainloads, had been gassed and cremated here. And of all these thousands of people not the tiniest speck of dust had been left behind in the ovens.’

After this disheartening experience for Morgen, the tour was resumed through the rest of the camp. He was shown a prisoners’ barracks, cultural things and a hospital ward. He also was shown the Bunker - the camp prison —in the Stammlager. There he was shown, quite openly and willingly, the so-called black wall where the executions took place.

Late afternoon the tour came to an end and it was time for action.

Morgen had the entire SS camp staff fall in in their quarters. They were ordered to stand in front of their lockers which were to be investigated by Morgen. As expected, he discovered all sorts of suspicious articles: gold rings, coins, necklaces, pearls, currency from all over the world. In one locker a few “souvenirs” only, in others a small fortune.’

© Kevin Prenger 2021, 'A Judge in Auschwitz: Konrad Morgen's Crusade Against SS Corruption & 'Illegal' Murder'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Swords Publishers Ltd.

Recently on World War II Today …

Marauders capture airstrip

In February 1944 the 2,750 men of the U.S. 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) marched into the Burmese jungle. They were also known as 'Galahad Unit' and are better known today as Merrill's Marauders, after their commanding officer. They were a deep penetration force travelling across country, like the Chindits they were dependent on air drops for resupply.