'With the East Surreys'

A reconstruction of one British Army regiment's war - this excerpt focuses on the crossing of the Rapido River on the night of the 11th/12th May 1944

‘With The East Surreys in Tunisia and Italy 1942 – 1945: Fighting for Every River and Mountain’ is the reconstruction of the war as experienced by two typical English regimental battalions - the 1st Battalion and the 1st/6th [Territorial] Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment. Raised in the gentle farming country and suburbs of outer London these men became mountain warfare experts in the tough slog through Tunisia, Sicily and Italy. The 1st Battalion left Britain for North Africa with 796 men. By the end of the war they had suffered 1,311 casualties - only 18 men survived with battalion all the way through.

Drawing on many personal accounts, Bryn Evans traces the different actions that these men took part in. The following excerpt describes their part in the final assault on Cassino, where the Rapido River formed the front line in front of the German positions:

1/6th Surreys in the first crossings of the Rapido

After the third Cassino Battle the l/6th Surreys had withdrawn with 4th Division for rest and recovery at Barracone in the valley of the River Volturno. At first there were hot baths, decent meals, real beds, and even a day or two's leave in Naples. Then the grim reality returned, as they commenced training in river crossings of the Volturno in small assault boats which could be carried in pieces and assembled near the river bank. Once across the river they exercised in both infantry and tank support attacks.

The rifle companies repeated the training ad nauseam, until they could assemble, launch, embark, cross and land, quickly and quietly in the dark, over the fast flowing Volturno, to be ready for the similar Rapido River.

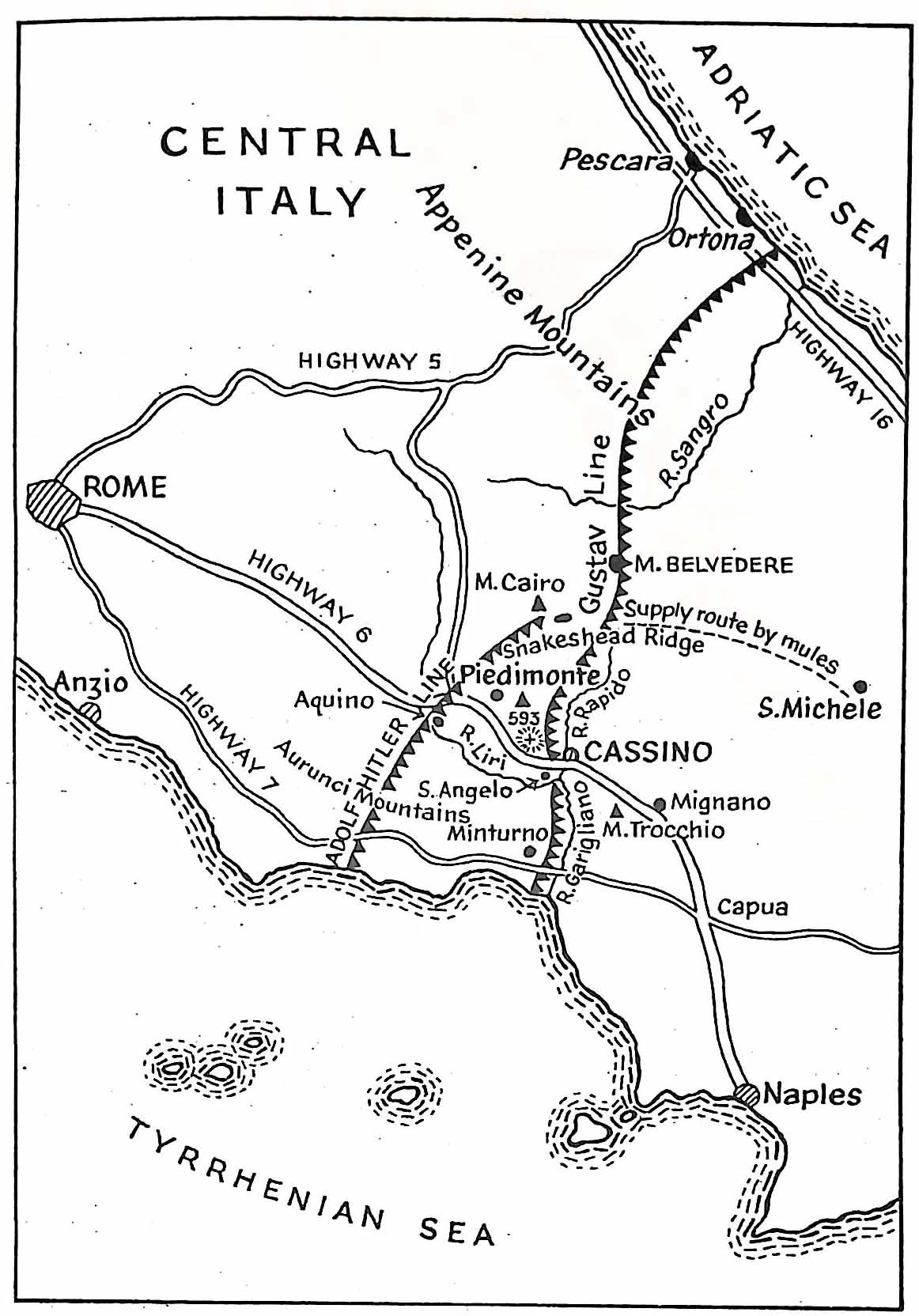

With 10 Brigade the 1/6th Surreys would lead 4th Division on the right, to cross the Rapido River, in places up to eighty feet wide, and seize a bridgehead between Cassino and Sant'Angelo. The Surreys' crossing point, codenamed 'Rhine', was a mile and a half below Cassino town, where the banks were up to seven feet high.

Another mile or so farther downriver at the 'Orinoco' crossing point, 28 Brigade would enter the river at the same time as the Surreys. Behind 4th Division, ready to cross and exploit either bridgehead, was 78th Division including 1st Surreys. The orders for the river crossings by 1/6th Surreys, and other battalions to follow them, were to push out through their bridgehead a certain set distance, then to swing to the right towards Cassino, which lay about two miles from the river crossing.

On the evening of 9 May 1/6th Surreys drove for two hours up Route 6 to stop near Monte Trocchio, their base for launching the river crossing. Secrecy regarding their move was maintained by leaving their camp with no indication of their departure. Their training boats and other equipment were left as if they would be returning.

During 11 May everyone remained concealed, weapons were cleaned and oiled, letters were written home and everyone rested. It was a beautiful day and very peaceful, and as the operation orders were given and every point explained, the contrast between the quiet of the day and the fury of the battle to come was very marked.

However, training to cross a fast-flowing river at night, without anyone trying to shoot you was all very well, thought Harry Skilton in 1st Surreys. To attempt it under fire, then get ashore and fight for a bridgehead, was an entirely different kettle of fish. Being attached to 1st Surreys' HQ Company, he knew something of the plans for 1/6th to be in the forefront of the coming attack. He had friends in 1/6th, and wondered if he would see them again.

Once across the river 4th Division had to gain four sequential lines of advance, each at intervals of some 1,000 to 2,000 yards. But lines drawn as objectives on a map could not show the reality of the terrain, or the terror, the certain casualties and the German troops to be overcome. It was known that there were mines on both sides of the Rapido and enemy snipers were hiding anywhere in the trees. On the far side of the river stretched flat fields interspersed with drainage ditches. Overlooking this killing ground, to the left across the Piopetto stream in Square Wood, and to the right on a rocky bluff, Point 36, the Germans watched and waited in strength.

On the right of 10 Brigade and 4th Division, 1/6th Surreys led the Rapido crossing. The Surreys' Beachmaster, Major Charles 'Banger' Nash, and a group of his men managed to porter the components of the assault boats to a spot very close to the river.

As this party could not leave the lying-up area until dusk they had to do their job very quickly. Major Nash and his sixty-two men ran the mile and a half to the boats, and then worked feverishly at their task, erecting and laying them out ready for the assault parties. It had to be done in absolute silence, only 400 yards from the river, with the enemy in positions right up to the river's edge.

It was a warm-scented night, and very quiet. As the companies moved stealthily down towards the river, the nightingales were singing. At ten minutes to eleven, however, the peace of the lovely Italian night was shattered by the sudden roar of the massed guns of Eighth Army. It was a most awe-inspiring manifestation of power, the loud continuous thunder of the guns, the screech and whine of the shells in the air, and the explosions as they landed amid the German positions. The sky around Monte Trocchio was illuminated by thousands of gun flashes, and the air vibrated from the continuous explosions.

...

On the night of 11 May 1/6th Surreys' Lieutenant H.G. Harris led a platoon in D Company across the Rapido river and into the hell of the fourth battle for Cassino. Because he was an accomplished swimmer, Harris would go first, and carry a rope across to the north bank. Once secured and pulled taut, it would allow his men in the assembled boats to shuttle themselves and their supplies across. He looked at the river, and in the dark he thought it to be no more than half the length of a cricket pitch. The problem was the current was flowing fast.

The far bank rose up in a mound like a dyke at the water's edge, and Harris knew that the Germans would be dug in on the other side. Would they have a lookout on watch? The night was eerily quiet, as if it sensed the impending artillery bombardment of Eighth Army. Gazing at the black, swirling water, he hoped against hope he could make the swim with little or no sound.

Surprisingly Harris chose to dive in. It was a clean dive, with hardly any splash, and after a few strokes he reached the other side with minimal downstream drift. Almost at once he found and grasped hold of some half submerged tree roots. Now even more conscious not to make any noise, he tied the rope around them.

Up against the bank and hugging the tree roots, Harris forced himself to stay still, the icy water reaching up above his waist. From the other side of the bank he could now hear the muffled chatter of German troops. There were only a few minutes to go, he knew, before the shelling began. Hopefully the enemy did not.

Would the shells land the planned ten yards beyond the river's northern edge? That kind of accuracy he found hard to believe. Then the first salvo hit, and it was on target. Immediately the first of the assault boats began to ferry across men and supplies. Under the bombardment's cover, and not least its noise, the men of Harris' platoon joined him, either onto the bank's slope or into the water's shallows.

There they waited. The shelling would lift fifty yards farther on after five more minutes. The moment it did, Harris was thinking, they had to be into the Germans before they had lifted up their heads. He peered at his watch, and wished them to be slow to react. Before the final seconds had ticked over, he slapped the man next to him, and went into a rolling kind of dive over the bank's brow. Once over, it surprised him. The closest German positions were well visible, lit up in the incessant shell explosions.

I spotted a dug-out about five yards to my right. I had come over the bank with a grenade in either hand, the pins already out as I pulled them from my webbing belt. The grenade in my right hand went into the dug-out, which I thought was the source of the voices I had heard while hugging the bank. The one in my left hand went in the general direction of a machine-gun pit…

The grenade explosions ignited an instant response from an uncountable number of Spandau machine guns. As previously ordered the platoon sections following his lead then spread out, and went to ground where they could, pinned down by the hail of fire descending on them. Their perilous position prompted Harris to radio Battalion HQ, for mortars to shell the ground between them and the German positions with smoke. It was the only way to give them a chance, he thought, by rushing each enemy dug out under the cover of hopefully dense smoke, and using grenades to fight a way forward.

By first light Harris learned the depressing news that only two sections of the other two platoons of D Company had crossed the river intact. In fact the D Company commander, the other two platoon commanders, and the Company Sergeant Major of HQ Platoon were all dead. When he informed Battalion HQ by radio of this catastrophe, Harris was promptly informed that he was now in command of D Company. He must at once bring the other sections of men on his side of the river, into his area, and was ordered to try and enlarge the fragile bridgehead as much as he could.

They soon found themselves in a murky fog of confusion. Smoke from the bursting mortars and other shelling soon obscured anything beyond about ten yards away. Firing seemed to come from everywhere, whether it was their own Bren guns or the Spandaus. Rope pulleys were rigged to drag supplies of rations and ammunition over the river bank in sand bagged packs. Anyone foolish enough to clamber over the bank would surely be riddled with bullets.

From thereon day after day, Harris and the remnants of D Company who eventually got across the river to join his new command began to fight their way forward from one German trench or machine-gun pit to the next. It was all crawling, clambering and slithering, until they were near enough to throw grenades. Only the odd extra-deep dug-out gave them an opportunity to stand upright. They did it for seven days and nights, until they reached Highway 6 in the Liri Valley.

© Bryn Evans 2012, ‘With The East Surreys in Tunisia and Italy 1942 – 1945: Fighting for Every River and Mountain’. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Swords Publishers Ltd