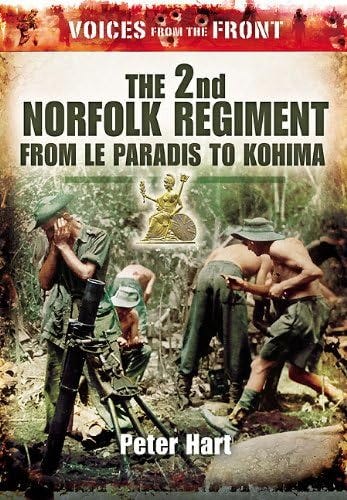

'From Le Paradis to Kohima'

The story of one battalion in the British Army which suffered a notorious massacre at the hands of the SS in 1940 and later fought in Burma

In the 1990s, Peter Hart, the oral historian at the Imperial War Museum (IWM)), participated in a project to record the Norfolk Regiment veterans' memories of their war experiences. The IWM made many thousands of such recordings. But in the case of the 2nd Battalion, Norfolk Regiment, Hart managed to have the recordings transcribed and put them together in a comprehensive history.

The 2nd Norfolk Regiment: From Le Paradis to Kohima (Voices From the Front) is the story of one Battalion in the British Army, told directly and vividly by men of all ranks. It gives a full picture of life in the regular Army before the war, during the worst episodes of fighting in France in 1940, and of fighting the Japanese in Burma.

Hart managed to reconstruct the 2nd Norfolk's participation in the Battle of Kohima using many firsthand accounts. After their first engagement at Kohima they were redeployed in Operation Strident an ambitious plan to march around the Japanese positions and attack them from the rear. Marching across this terrain looked impossible - it was hoped such an approach would have the benefit of surprise :

The last-minute preparations were chaotic, and in the morass of last-minute instructions, Robert Scott [Lieutenant Colonel, commanding the 2nd Battalion, Norfolks] managed to pick a fight with Grover [Major General commanding the 2nd Division] over the vexed issue of tin hats.

Then there was a funny little thing about hats on, hats off! Which is a great joke. Robert Scott said, "Bush hats will be worn!" General Grover said, "Tin hats will be worn!"

Robert didn't mind what he said, to whoever they were, he said, "Well that's a bloody silly order, Sir! They'd be much better if they had bush hats, much easier for the men".

John Grover said, "Yes, I hear what you say, Robert, tin hats it is and stop arguing!" So we were hats in, hats out of our kit-bags, one moment it was bush hats, then it was tin hats and we ended up with tin hats!

Lieutenant Sam Hornor, Signals Officer HQ Coy, 2nd Norfolks

The men were laden like packhorses, as everything they needed had to be carried. There was no question of any kind of transport accompanying them.

We were issued 100 rounds of ammunition in addition to what we already had. This we dangled round our necks in two bandoleers. Blankets were cut in half, we rolled half up and put it on the back of our pack. Every third man was given a shovel, every third man was given a pick, and the other third were given two carriers of mortar bombs.

Sergeant Fred Hazell, DCoy, 2nd Norfolks

The stronger men carried even more. 'Winkie' Fitt was now coming into his own as active service beckoned and he had been placed in command of No. 9 Platoon of B Company. His personal load would have tested a pack mule.

Around my body, around my web belt, I had grenades all the way round. Other people that could, that were strong enough to do it, did the same. We also carried bandoleers of ammunition which we strung over our shoulders or around our neck. I had about five or six bandoleers. About fifty rounds in a bandoleer, I suppose. On top of that we had our ammunition pouches full. We were carrying anything and everything that we could in the way of ammunition and rations. We didn't expect the climb and the march to be quite as fierce as what it was.

Sergeant Bert Fitt, B Coy, 2nd Norfolks

Hazell also made his own more personal preparations for 'Operation Strident'.

This truck turned up so I nipped down there and I bought myself six cans of evaporated milk, half a pound of tea and about three pound of sugar. My pack was already stuffed tight, but I managed to get this lot in because I didn't want to go on this three-day trip without plenty of brewing up gear!

Sergeant Fred Hazell, D Coy 2nd Norfolks

It was known that there was a track of sorts leading to the Naga village of Khonoma. After that the country was considered to be almost impenetrable - certainly by a formation of armed troops. The maps were of limited use.

...

Many officers, however, were less than impressed with the maps when they were distributed.

We were looked at them and there was the map showing where we were going. It was absolutely white because it had never been surveyed, nobody had ever been there, the Nagas said they didn't go there because there was a lot of superstition about it - there were witches and that sort of thing. All there was, done from aeroplanes, was a few little nalas, watercourses and the rest of it was white - so it was a fat lot of use having a map!

Lieutenant Sam Hornor, Signal Officer, HQ Coy, 2nd Norfolks

As the Iron Bridge area was under distant Japanese observation they set off on the march at about five o'clock in the evening, just as it started to get dark.

The path went up a steep valley between wooded slopes and climbed steadily, sometimes through trees and sometimes among paddy fields; often, it became indistinguishable from field paths, which led only to other areas of cultivation.

Captain John Howard, Intelligence Officer HQ, 4th Brigade

The first stage, although through a cultivated area, still posed difficulties for the troops.

It was very nasty; some of us were walking across paddy fields, not across the actual field itself but around its outskirts. They were built up like a ridge, and they stank - have you smelt dead earth - it was horrible.

Bugler Bert May, HQ Coy 2nd Norfolks

Gradually they climbed up into the hills, with all the usual problems of marching through rough country with little or no light. Smoking was forbidden and every effort was taken to keep noise to a minimum.

God what a night that was! What a climb! What a climb! Very steep, wooded, a lot of undergrowth. There were a lot of paths, but occasionally, we had to cut our way through. I stepped on a moist tree root, lost my footing and fell flat on my back. My legs went in the air, and unfortunately, I caught the chap in front on both legs, just above his knees, and he was the biggest chap in the battalion. He came down on my stomach and God, he knocked every ounce of wind out of me. You couldn't hang about because it was pitch, blooming dark and if you lost the chap in front, you could end up anywhere.

Sergeant Fred Hazell, D Coy 2nd Norfolks

Eventually, they arrived at Khonoma, a village that had featured before in the proud annals of the British Army. For in 1879, it was here that Lieutenant Ridgeway of the 43rd Bengal Light Infantry had won a posthumous VC fighting the self-same Nagas, who would soon prove themselves indispensable to the Norfolks.

We finally arrived at this blessed village at about two o'clock in the morning. Somebody from headquarters came up and said, "Put your platoon in there!" This was quite a big hut. We went in, pitch dark; I sat down on my backside, took my pack off and decided I was not going to carry this evaporated milk, not another inch! I drank four cans of it before I fell asleep. Long before I'd finished, the whole platoon was snoring its heads off! I fell asleep myself.

I woke up, the sun was shining through the chinks in the walls of this hut and I thought to myself, "Gods' strewth, I never posted a sentry!" I opened the door and there was a big Naga standing outside 'On Guard' with his spear. He looked round and he beamed at me, I patted him on the head.

Then somebody appeared and said, "Have your breakfast, we're moving off at ten" 'Breakfast' was three biscuits and a brew up.

Sergeant Fred Hazel, D Coy 2nd Norfolks

For the next three days the column moved mainly during the day, shielded from prying Japanese eyes by the thickness of the precipitous jungle ravines and ridges that surrounded them before tumbling down towards the Kohima road.

© Peter Hart 1998, 'The 2nd Norfolk Regiment: From Le Paradis to Kohima (Voices From the Front)'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Swords Publishers Ltd.