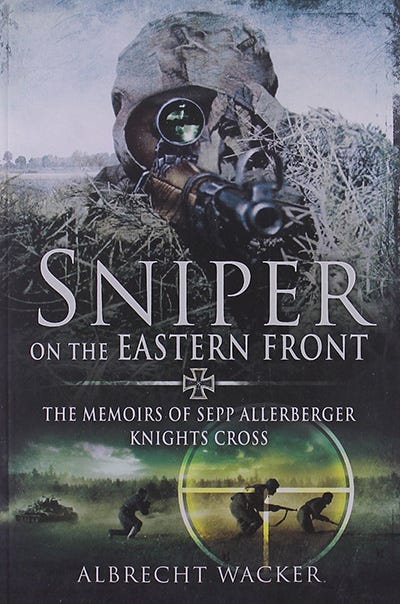

'Sniper on the Eastern Front'

An excerpt from a graphic account of the reality of life for German soldiers as they faced the Red Army onslaught in early 1944

Jozef ‘Sepp’ Allerberger was the second most successful of the Wehrmacht snipers during the war, credited with 257 kills, one of just a few ordinary soldiers to win the Knights Cross. A carpenter's son from Austria, he became a self-taught sniper after experimenting with a Russian weapon during a period of convalescence - killing 27 men before he was sent for formal sniper training. His memoirs were produced after many months of interviews with Albrecht Wacker, producing a distinctive account of how the German infantry lived and fought in the second half of the war on the Eastern Front.

This excerpt from Sniper on the Eastern Front: The Memoirs of Sepp Allerberger describes the situation that the men of 3rd Gebirgsjäger Mountain Division faced at the beginning of 1944:

The thaw had started, and the riflemen had to make their way through a morass that was often knee-deep. Their shoes and trouser legs were so soaked with water and caked with mud that they could hardly move their legs. Physically exhausted, they dragged their feet along as best they could. Many of them were so tired that they slowed to a standstill and fell asleep where they stood. Their comrades grabbed them by the hand and pulled them on, and minutes later they awoke with a start and could not even remember how they had moved. The strain of the march was so overwhelming that even the pills, of which they were taking considerable quantities, had only minimal effect.

Sepp carried his gun on his back, its telescopic sight wrapped with bits of a tent square to protect it from the mud, and around his neck was slung an MP40 in case there should be a surprise firefight. He had become accustomed to staving off his tiredness and hunger by chewing dry biscuits, which he obtained by swapping his cigarette ration when he could.

Behind the Russian moves there lay more than just a transfer of their focus of attack. Their operation developed into a huge offensive, which inflicted serious damage on the German lines on 30 January 1944. At the confluence of the Basawluk and Dnieper rivers two German armies were suddenly at risk of being encircled.

As so often before, an urgent request to shorten the German front was refused by Army Headquarters for so long that when permission finally came it was almost too late. Fortunately the clumsy Russian leadership helped them by dividing the Soviet forces at the decisive moment instead of keeping them concentrated, and the German commanders were able to transfer sufficient units to the threatened sector to frustrate the attack.

The exhausted Gebirgsjager plodded wearily on through the mud. The higher purpose of their ordea lwas not clear to them. Now they fought and marched without even thinking rather than because of any personal desire to survive. They had become warriors, bound together by comradeship and the ever-present threat of death.

There were no breaks any more. The riflemen were like zombies. In their wet winter fighting suits, their faces drawn by hunger and fatigue, they were just drawn along by the vortex of events surrounding them.

Sepp finally became sick. His constant exposure coupled with drinking water scooped from bomb craters gave him a severe bout of gastro-enteritis. Gripped by a shivering fit, he did not know from one minute to the next what he should do first, shit or puke. Captain Kloss, the battalion commander, found him shivering in the corner of his dugout, curled up like a wounded animal.

Captain Max Kloss had taken over II Battalion when it moved into the Nikopol bridgehead. Driven by a desire to serve the Fatherland wherever it was most necessary, he had volunteered to transfer from the Lapland Front to the Eastern Front. He was inspired by a firm belief that National Socialism was a good thing, and he wore a Hitlerjugend badge on his uniform as an expression of his conviction. But he was no blind party supporter, but rather a committed and brave soldier.

When he saw Sepp squatted down and trembling, he asked the company commander who he was. The latter explained that Sepp was 7 Company’s marksman, and that he was very good at his job. ‘We need every specialist,’ said Kloss. ‘This man has to get fit again. He’s the very last marksman we have in this mess. I can’t lose him too.’ Kloss told Sepp to go to the battalion command post and seek out the battalion runners. ‘Tell the boys that they must care for you.’ Then he turned to the company commander and said: ‘I hope you don’t mind, lieutenant.’ The latter just shrugged.

Still trembling, Sepp trudged away. It was only about a kilometre to the battalion command post, but he had to pause and shit again and again on the way. Finally he arrived at the runners’ dugout, collapsed as he entered the improvised resting place, and moaned: ‘The old man said you should care for me. In particular I need a new pair of underpants.’ ‘Of course, Miss Allerberger,’ came a voice from the back of the cave-like room. ‘Mister Professor and his carbolic mouse will come to powder your sore arsehole.’

But they really cared for him. They got him black tea and found a highly effective diarrhoea medicine called Dolantin,produced by a company called Hoechst. This not only had a pain- relieving effect but was also antispasmodic. It considerably eased the painful side effects of diarrhoeic diseases.

But Dolantin found its true destiny as a painkiller after the Hoechst chemists managed to increase its effectiveness by a factor of twenty at the beginning of the 1940s. This stronger version was given the name Polamidon. Germany’s enormous need for pain-relieving medicine is witnessed by its production of 650 tons of the stuff in 1944.

Dolantin, rest and appropriate food eased Sepp’s intestinal cramps and diarrhoea. The care he received from the runners was phenomenal, and in a few days he had recovered. Now and then Captain Kloss came round to ask about his state of health, and then they started talking and realized that they got on well with each other.

Sepp’s legs were still a bit shaky, but Kloss said: ‘It’s time for you do something again. We’ve got four new sergeants. They’re for your company. I thought you could take them under your wing, escort them over there and show them what to do. My driver will take you.’ Less than a quarter of an hour later they set out in a VW jeep, but their ride ended after just a few minutes when a loud detonation rammed the steering wheel into the driver’s hands with an iron fist. The car swerved to the left and tipped on to its side with a lurch.

Sepp heard himself scream ‘Shiiit!’ as he and his comrades were thrown out into the mud at the side of the road. Everybody knew that they had driven on to a mine that had torn off the left front wheel, so nobody dared to move. They kept lying where they were. ‘These fucking things must be ours!’ said the driver. ‘Yesterday it was clear through here, and Ivan hasn’t got here yet. Anybody wounded?’ Apart from some bruises they had all escaped unhurt.

They crawled back to the car on all fours, feeling the ground carefully with their fingertips. They were discussing what to do next when a group of engineers came in their direction in single file. ‘What are you housewives doing here?’ said one. ‘Did anybody say you could mess up our lovingly installed mines?’ The brutal cynicism of this slender joke was not well received.

‘You arseholes will get something in your face. You’re supposed to tell us where you put our mines!’ ‘Well, now you know about them,’ they were informed by the engineers’ leader, ‘and if you keep on grumbling we’ll just leave you sitting there. I suggest you follow us very carefully.’ ‘Follow them,’ said the driver. But the way to Sepp’s company was now blocked, so the group returned to the battalion command post and reported to the old man. Thereafter Kloss kept Sepp at his personal disposal with the battalion runners.

© Albrecht Wacker 2005, 'Radio Operator on the Eastern Front'. Reproduced courtesy Pen & Swords Publishers Ltd

Recently on World War II Today …

As a result it was absolutely vital to demonstrate an iron will. Any further withdrawal ultimately meant defeat for Germany. From now on a general or officer who suggested to him that there should be further retreat he would punish severely or simply shoot.