A Tailor in Auschwitz

Reconstructing the journey of a doomed family - and of millions of others - through the life of the sole survivor

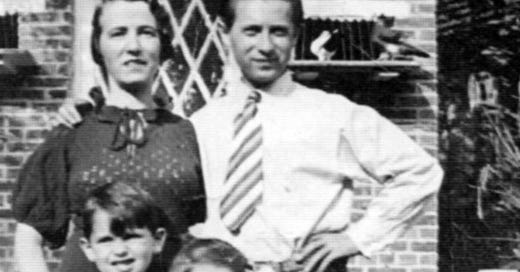

Ide Leib Kartuz moved from Poland to Antwerp, Belgium, in 1929 to escape anti-semitism. He established himself as a tailor, married Chaja Artman and fathered two children, Charles-Victor and Simone. But Nazi antisemitism was even more virulent and far-reaching than the attitudes Ide had encountered in his youth. In 1942 the whole family was deported to Auschwitz. Only Ide was to survive the war.

In 2018 Ide’s grandson David van Turnhout set about reconstructing his grandfather's life and journey across Europe. Together with Belgian academic Dirk Verhofstadt, he visited the locations in Poland, Belgium and Germany that marked his grandfather’s odyssey - and uncovered a remarkable number of eyewitness accounts from people who had the same experiences in the same places, often at the same time. They matched these recollections against the Nazi records that remain to this day.

The result of their research A Tailor in Auschwitz is a detailed picture of the experiences of millions of people - and how they spent their last days - as represented by one man.

The following excerpt (released on Holocaust Memorial Day) describes how Jews from across Europe were received in Auschwitz up until 1944, which the authors visited with expert guide Dorota Kuczynska:

From the summer of 1942, hundreds of thousands of Jews from all over Europe arrived at this Judenrampe,’ says Dorota.

Victor Vrba, who managed to escape from the camp in 1944, wrote about this in his book I Escaped from Auschwitz:

‘A huge, bare platform that lay between Birkenau and the mother camp and to which transports rolled from all parts of Europe, bringing Jews who still believed in labour camps.’

Vrba saw 300 transports arrive there over eight months. Today there is hardly anything left of the platform, but in the past, there was a vast railway yard with the name Bahnhof West. ‘It was built at the same time as Birkenau,’ says Dorota.

In his book Auschwitz, De Judenrampe, the Dutch writer, artist and grandson of an Auschwitz-survivor, Hans Citroen, describes this dilapidated station.

‘The Jewish platform [was] a 500-metre-long wooden platform built at the beginning of 1942, with tracks on both sides along which in 1942/1943 transit tracks for the supply and disposal [of Jews] were subsequently built as well as sidings for the storage of unused wagons.’

With the help of military aerial photos of the site and eyewitness reports, Citroen establishes that the Rampe was 35-metres wide with tracks on both sides. The original tracks were enlarged to eighteen separate tracks to accommodate not only the incoming transports with prisoners but also the equipment and soldiers.

Every day one or more trains arrived here; sometimes they were 1,000 metres long. Most wagons contained human cargo. As there were sometimes so many arrivals, trains often had to wait for hours and even days. The crowded, confined conditions in which the Jews found themselves must have been unbearable on very hot or cold days.

‘On the sidings long rows of freight wagons with thousands of people packed like sardines often stood there for days on end without food, drinks or sanitary facilities. They cried out for water.’

Eventually the wagons were opened. ‘Here the deportees had to get out into a world completely unknown to them. But the spotlights and yelling guards with dogs must have immediately scared them,’ according to Dorota.

The doors flung open, and SS men and some inmates in striped uniforms hurried the Jews off the trains. To speed things up, they screamed and pushed those who hesitated. There were kicks and blows, though the guards rarely went further. Restraint was more likely to guarantee order and compliance, since it helped to deceive the victims about their fate.

The Jews had to get onto the wooden platform as quickly as possible and stand in rows next to the railway track. Immediately afterwards selections started. Trucks waited near the stopping place. The bodies of the people who had not survived the train journey were loaded in the first trucks. The remaining trucks were for the disabled and the senior citizens. Women with babies and children were also removed with the trucks.

The other selected Jews had to line up, were no longer allowed to speak and had to leave for the main camp on foot. A gravel road that led to Birkenau was approximately one kilometre long. A different road of about a kilometre and a half led to the main camp in Auschwitz. The original place of arrival no longer exists. Instead a rather symbolic monument has been erected. ‘The current Judenrampe with the two freight wagons was built in 2005 as a reminder of the place where more than 600,000 Jews arrived until 1944,’ says Dorota.

From the spring of 1944 the train tracks were extended inside the Birkenau camp to 100 metres from the gas chambers and crematoria. That image in particular is what most people associate with Auschwitz. Another half million Jews arrived through this gate from April 1944, mainly victims of the Hungarian Holocaust.

We look bewildered at the tracks and the two wagons. This is the place where Ide got off the train on 27 August 1942, where his life took a dramatic turn and where his wife and children would disappear from his life forever.

We can only guess how Chaja, Charles-Victor and Simone felt when they were shouted at to get off the train. They must certainly have been extremely anxious and confused. Would they have cried? Did they see their dad? We can only hope that they did not suffer too much. That they didn’t get too many beatings and that they were allowed to Stay together. That the warm hugs of mother Chaja was the last thing the children were allowed to feel when they were crammed into the gas chambers with hundreds of other naked people.

‘The symbolic wagons on the Judenrampe have no windows. Could it have been third-class carriages with at least two access doors?’ ‘Yes, that is quite possible,’ says Dorota. From wealthy countries such as Belgium, France and the Netherlands, they arrived with such carriages in 1942. At the front of the Judenrampe we see the gravel road.

This road now starts next to a villa with a garden with toys for children. Along this road Chaja left with the children, by truck or on foot, towards the gas chambers. According to Dorota, the gassing took place the same day in the Little Red House on the outside of Birkenau. The farm was about two and a half kilometres from the Judenrampe and was built from red bricks. The building had four rooms.

In March 1942 prisoners of war knocked down the interior walls, bricked up the windows and converted the rooms into two gas chambers, each with a hermetically sealed door.35 At the top there was a hatch through which an SS soldier could sprinkle the Zyklon B and then close it with a lid. Each room had a maximum capacity of 400 people. This allowed the Nazis to gas 800 prisoners in one go.

Subsequently, members of the Sonderkommando opened the rooms and dragged the dead bodies out. They took the corpses to mass graves on the edge of a nearby forest via a narrow track and with carts. From August the corpses were also burned. Today there is nothing left of the Little Red House. The building has been demolished. On a small fenced piece of pasture stand three black tombstones to commemorate this terrible place and the mass murders that took place here seventy- nine years ago.

While his wife and children were being deported, Ide was selected to work. He lined up with a hundred others in a row next to the Judenrampe. When asked whether this could have been a Kommando (work unit) for tailors, Dorota answered in the affirmative. ‘That Kommando went on foot to the main camp under SS surveillance. The road to it runs in the opposite direction from the gravel road to Birkenau.’

Thus, the testimony of Majzels and Mandelbaum about the selection of 101 tailors appears to be correct. The subsequent events after the arrival also gradually become clear. Mandelbaum explains in his testimony that he marched with the group under the surveillance of SS soldiers for about a mile and a half further to the Stammlager Auschwitz.

Then they arrived at a gate with the cast-iron text Arbeit Macht Frei, a statement that camp commander Hoss had chosen himself. The paths and blocks were neat.

‘I thought: how beautiful is that. We walked along a wide avenue with flowers on the side. Then along a building without floors with a chimney. I wondered what that was. But then I saw at least seven dead bodies on the side of the road.’

Only then did he realise that they had ended up in a horrific concentration camp. Ide must also have realised this when he marched into the camp with the other selected tailors.

Mandelbaum continues that at the end of the avenue with the beautiful flowers they had to walk to the right, between two buildings and completely undress. Then four prisoners pushed a cart with clothes towards them. Some items of clothing were bloodstained. The prisoners did not talk to the newcomers. The latter were also not allowed to talk to them.

The newcomers did not fully understand what was about to happen to them.

‘First, they completely shaved us, everywhere. Then, they made us take a cold shower without soap, without a towel. We walked past prisoners holding a water container that smelled of petroleum. They rubbed us under the arms and between the legs to disinfect us.’

© David van Turnhout & Dirk Verhofstadt 2022, ' A Tailor in Auschwitz'. Reproduced courtesy of Pen & Swords Publishers Ltd.

Affiliate Links

References mentioned:

Victor Vrba: I Escaped from Auschwitz

Hans Citroen: Auschwitz, De Judenrampe

David Mandelbaum: Auschwitz Foundation DVD 1992.

Also on World War II Today:

The Holocaust in 1943

Official recognition by the international community of what was to become known as the Holocaust came at the end of 1942. However, the Allies were incapable of offering the Jews across Europe any significant material assistance. None of those taken away are ever heard of again. The able-bodied are slowly worked to death in labour camps. The infirm are le…