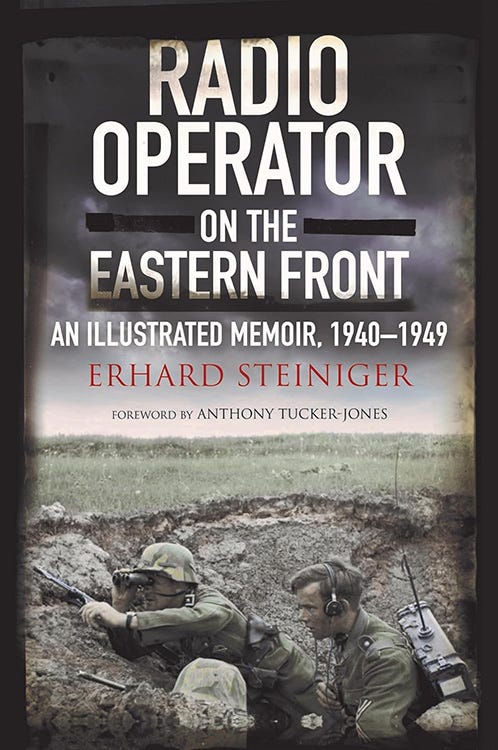

'Radio Operator on the Eastern Front'

A German soldiers account of defending the front outside Leningrad as the Red Army step up the pressure in the early days of 1944

Erhard Steiniger served with the 151st Infantry Regiment, 61st Infantry Division of the Wehrmacht from 1940 to the end of the war. His entire service was on the Eastern Front where he participated in the advance through the Baltic states and into Russia in 1941 - and then the retreat back into East Prussia in 1945. He then spent four years as a prisoner on war in Russia.

He wrote his memoirs, Radio Operator on the Eastern Front, in 1981 for the benefit of his family. They were not published in English until 2020. He appears to have access to some records that helped him recover his memory of events and dates, although it is not based on a personal diary. Nevertheless it is a remarkably detailed account on the conditions in which men fought - and the circumstances in which they died.

The following excerpt covers an especially memorable few days in January 1944:

THE CHRISTMAS lull did not deceive me into believing that the winter offensive was not coming. When it did come, the location chosen by the Russians for their breakthrough was the Oranienbaum Pocket near where the former sanatorium had been. We had only the inexperienced 9th and 10th Luftwaffe Divisions deployed along the semi-circular land perimeter.

We had arrived near Oranienbaum and spent the night in solid concrete bunkers. Looking east from there one could see the suburbs of Leningrad and a lighthouse with a flashing light.

The only thing certain about 14 January 1944 which I remember, the most difficult rearguard action our regiment had ever had to face, is of our infantry companies being surprised by tanks coming at them from all sides most unexpectedly, and suffering very heavy losses. Bubi Buchs fell and Werner Zahn is missing since then. I have no memory of what happened to my radio apparatus.

My ability to recall the early stages of that retreat is not good. Our weak lines had been overrun suddenly by strong tank forces and now we marched - if that is the correct word - in an endless crowd of troop members ranging from clerks to Tross operatives, infantry companies, signals people, messengers and so on in a direction which was roughly west.

However I do recall Feldwebel Noack of the regimental office. He was normally a very calm person, unhurried and had a deliberate way of speaking. We had come under artillery fire and I found myself running in search of cover with him. There must have been a sporting side to his nature of which I was unaware for he could run at double-quick pace and I found it difficult to keep up. We were heading up a hill with two tanks behind us and got to the brow before they had a chance to bring their guns to bear. In those seconds we found a place on the elevation which was a blind spot for their gunners.

Our regimental staff gathered next day in a massive building resembling a castle to organise the next line of defence. Lacking my radio equipment I had to take ammunition forward on a sledge assisted by a Hiwi [Russian prisoner-volunteer]. I sat with him on the cases. The weather was fine and sunny. Trotting ahead of the sledge was a small but tough Russian horse of the steppe. It was no great distance, for the company command post was located in a small farmhouse not far from the 'castle'.

I was surprised to be approached by the former Gefreiter Hegele of the 2nd Battalion signals staff, the close-combat specialist of Nevabogen, now an officer and company commander. When he saw my reaction to his promotion he gave me a friendly grin while maintaining his distance as an officer.

Before either of us had the chance to speak, there were multiple whistling noises in the air and then explosions all around had us diving into a nearby haystack. Almost at once another salvo followed, and this time the Stalin rockets were so close that we felt the air pressure of the explosions on our eardrums. Leutnant Hegele, the Hiwi and I were uninjured but the little horse was trembling over its whole body. It was not wounded, but shocked and frightened as we were.

My Russki and I unloaded the ammunition boxes as fast as we could, and I paid my respects to Leutnant Hegele fairly rapidly. I never saw him again. He was reported missing next day. When I returned to the ‘castle’, it no longer had window panes, the Stalin-organ rockets had seen to that.

Next day the regimental HQ was pulled back to the rear. Major Brzoska, 2nd Battalion commander, fell that day. The new command post was set up to the north of a village, probably Kipen, in a house in its own grounds. The Leningrad-Narva Rollbahn passed at the south end of the village. The rearward services of all units rolled past here heading west, and we would be following them next day since we had no unit to support in the region.

He was hefty and well-fed, nothing like the Russian soldiers of two winters earlier.

Oberst Miiller-Melahn was in occupation of the house which overlooked a plain jutting to the west. Very well camouflaged in front of the entrance to the house were two anti-tank guns, one each of 3.7-cm and 5-cm calibre.

It was sunny, as usual for the season, tolerably cold and visibility was good. From the western edge of vision, between the plain and the wood, a string of T-34 tanks came rolling in line ahead. We counted seventeen, and could see that if they continued on that course they would meet the retreating Tross. We had no radio and looked on helplessly. Suddenly one veered towards us as if to investigate, front profile heading straight for our house.

The Herr Oberst gave his orders thoughtfully and warned us to keep quiet. ‘Just don’t panic,’ was his advice. We left the house by the back way, and at its rear watched the tank from the shadows. The T-34 had crossed the plain, its motor becoming more audible every second. If we did not succeed in destroying the tank it would crash through the house and hunt us down across the flat plain with its machine guns. Why didn’t the anti-tank guns fire?

The tank was scarcely twenty metres from the house when the 5-cm gun fired, hitting the commander’s cupola and jamming it. Then the stick-grenade fired by our 3.7-cm gun swept the turret away behind the tank to lie in the snow.

The only survivor, a warrant officer radio operator, was unhurt and surrendered. We took him prisoner into the house. He was hefty and well-fed, nothing like the Russian soldiers of two winters earlier. Bubi Muller, our ordnance technician, did not think it safe to enter a burning, damaged tank to plant explosives to destroy it, and so the T-34 was left to burn out and could be seen still smouldering when night fell.

A section of the regimental signals platoon was deployed in the infantry role that evening. Unteroffizier Dreihsen took over the seven-man group, its other six members being Wolfgang, Pat Wachnowski, Arnold Mathaus, Hans Kreiner, Bubi Reimann and myself. We were given guard duty until midnight when we could stand down. All we saw in the snowy fields was the odd cat, otherwise nothing to report except stray infantry fire coming our way from the rear.

© Erhard Steniger and Geoffrey Brooks ( translator) 2020, 'Radio Operator on the Eastern Front'. Reproduced courtesy of Greenhill Books and Pen & Swords Publishers Ltd

Recently on World War II Today …

Work resumes on 'Harry'

In Stalag Luft III a significant proportion of the RAF PoWs continued to regard it as their duty to attempt to escape. During 1943 they had had three tunnels underway - 'Tom', 'Dick' and 'Harry', in the belief that one of them must prove successful.

In the Eastern Front trenches

On the Eastern Front the Soviet Army had launched another offensive and were making good progress towards Poland. Yet other parts of the 1000-mile front remained static as the two sides faced each other from trenches. Most of the time the majority of men lived in bunkers dug into the earth, hidden under the snow. Only those on guard duty had to be out keeping observation, the remainder huddled together in the most cramped quarters. The typical Soviet bunker housed six or seven men with just enough room for them to lie down side by side and not enough height to stand up.