An insider's account of Hitler and his war

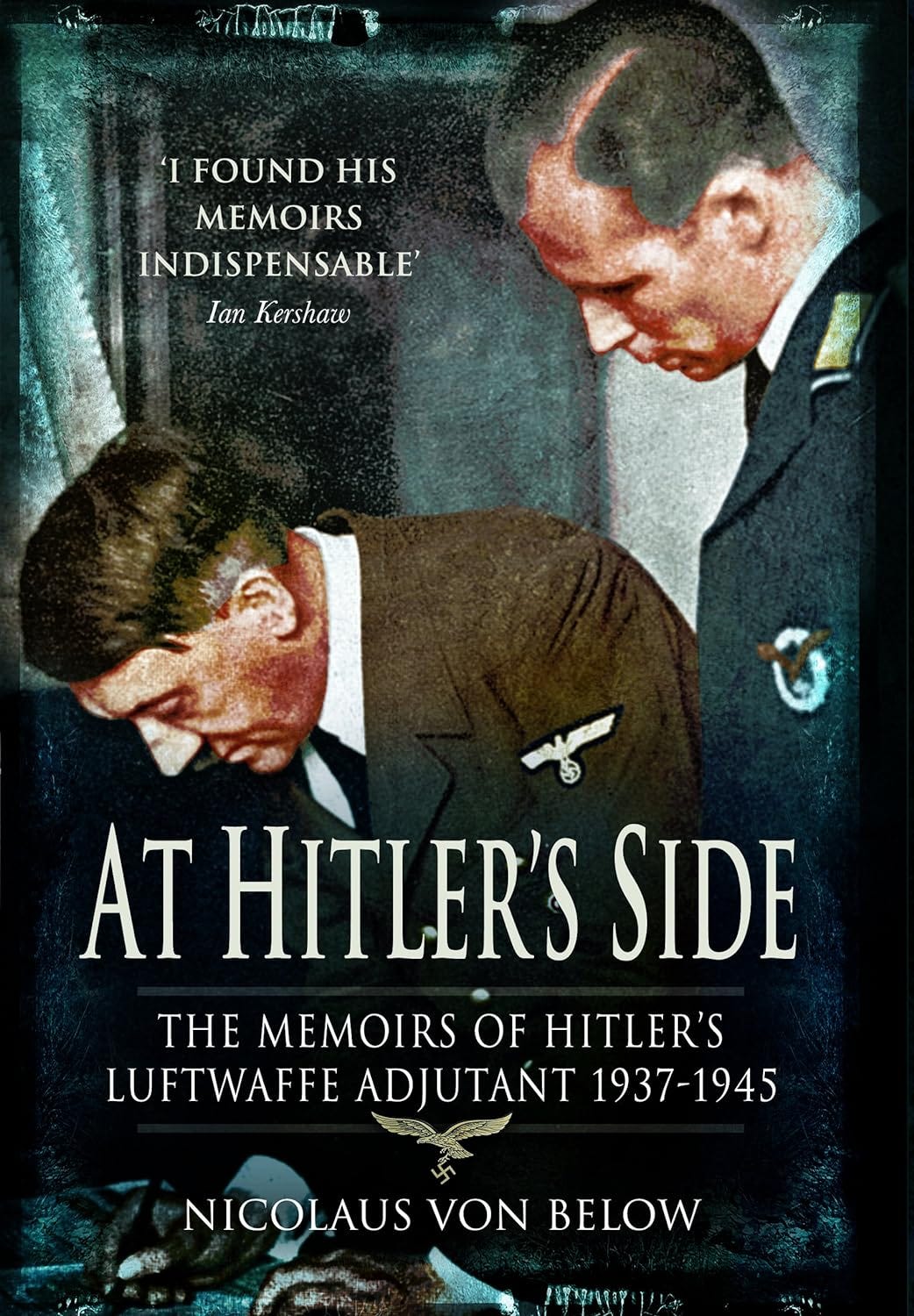

This week's excerpt comes from 'At Hitler's Side: the Memoirs of Hitler's Luftwaffe Adjutant'

Nicolaus von Below loyally served Hitler throughout the war. His recollections of events in At Hitler's Side: the Memoirs of Hitler's Luftwaffe Adjutant provide a unique insight into Hitler’s outlook as the war unfolded and the changing atmosphere amongst his inner circle.

The following excerpt gives an overview of how Hitler viewed the war at the beginning of October 1943:

Landings in Italy

In September 1943 the Allies landed in southern Italy. They moved up northwards relatively quickly as far as Naples and Foggia. The latter seemed very important to them: there were airfields there and favourable terrain to lay down more. This they accomplished in a few weeks.

In October the Americans flew their first major air raid from Foggia against the Messerschmitt factories at Wiener Neustadt which turned out the Me 109. Hitler sent me there at once in order to obtain clarification of the conflicting reports submitted by the flak units and Homeland Air Defence organisation about the strength and success of the attack. I had already experienced the impenetrability of the secret world of air defences. The responsible commanders here had not seen very much of what went on since there was no protected observation point where an air raid could be watched from beginning to end.

By the beginning of October, almost 300,000 Italian soldiers had been transported to Germany as prisoners of war and put to work. The Allied land forces took their time coming up from southern Italy and Kesselring, C-in-C South-West Army Group, was not only able to marshal his few forces for a spirited defence but became so firmly established that he allayed Hitler's fears about the Italian Front. Eventually, the theatre was left in his hands and Hitler hardly ever interfered there.

Further Intensification of the Air War

The Reich was becoming more and more the hapless target for British air raids. On 7 September Hitler asked Professor Messerschmitt how things stood with the Me 262, and, to everybody's surprise, if it could also be used as a bomber. Messerschmitt said that it could, and added that Milch was always making difficulties and not putting a sufficient workforce at his disposal.

This struggle between Messerschmitt and Milch had been smouldering for years. Explaining the problem to Hitler, I told him that Messerschmitt had already exceeded his entitlement having regard to the stage his developments were justifying. He had a knack of presenting individual achievements in such a way that it seemed he was ready to mass-produce. I requested Hitler to discuss the question again with Milch.

Hitler's main preoccupation at this time was anti-aircraft defence. He racked his brain day and night for new ways to reduce the effects of the bombing. Earlier he had left this job to Göring, but even the latter was now dissatisfied with results. Therefore Hitler consulted only the Chief of the Luftwaffe General Staff on Luftwaffe questions and ignored Göring, who began to appear more infrequently at daily situation conferences. The air raids increased.

On 2 October the fighter factory at Eden was seriously damaged, on the 4th the industrial area of Frankfurt and on the 10th Münster and Anklam in Pomerania. On 14 October the Americans carried out a heavy raid on Schweinfurt which virtually paralysed ball-bearing production. On this occasion the bombers suffered heavy losses. After this latter German success, which was due primarily to Hitler's persistent criticisms, the daylight attacks stopped. The British night attacks against cities continued, however, and Hanover, Leipzig and Kassel also received attention.

On 5 October Hitler discussed with Göring and Korten how the day attacks could be ended permanently. Hitler said that the major part of the fighter force ought to be concentrated to oppose the enemy bomber fleets. It was important to prevent the destruction of our production centres. After every air raid Hitler received reports from the appropriate Gauleiter. He was therefore in the picture about the completely inadequate Air Raid Defence organisation. Often, during the day attacks, it was next to useless. When fighters could not get up because of bad weather or were occupied elsewhere, this made Hitler especially irate.

What made it worse was when bombers protected by enemy fighters were not engaged by our fighters because of poor direction techniques. At situation conferences Hitler was able to present detailed reports about individual air raids and was swift to jump to conclusions based partly on his misunderstanding of air defence and partly on the conflicting reports submitted.

Hitler had been made aware of the Japanese kamikaze phenomenon, which had been advocated repeatedly in Luftwaffe circles on the premise that the sacrifice was justified if victory resulted as a consequence. He was not of this view. He thought that inspired, selfless commitment for the Fatherland was right, but this price was too high. The names of volunteers were noted, however, in case the need for German kamikazes should ever arise in the future.

On 7 October the Gau- and Reichsleiters were summoned to Wolfschanze to be instructed as to the unfavourable situation and the future difficulties to be overcome. Hitler emphasised that the will of the people and unremitting perseverance in pursuit of the goal' must remain constant, continuing: 'Your warrior spirit, your energy, your firm resolve and utter readiness give the people backbone and steadiness to withstand above all the violence of the bomber war.'

He closed with words expressing his unshakeable confidence in victory and succeeded in convincing his devoted listeners, who then returned to their Gaue in the firm belief that he had in preparation certain weapons which would yet win this war for Germany; his "Decree Respecting Preparations to Reconstruct Bomb-Damaged Cities" reinforced their hopes.

Hitler's Intransigence

Hitler foresaw threatening developments on the Eastern Front earlier and with greater clarity than his military advisers, but he was determined with great obstinacy not to accede to the requests of his Army commanders to pull back fronts, or would do so exceptionally only at the last minute. The Crimea was to be held at whatever cost, and he refused to entertain Manstein's arguments in the matter.

In October Saporoshye and Dyepropetrovsk were lost. On 6 November Kiev fell and fierce fighting continued in the bend of the Dnieper, yet Hitler informed Zeitzler and Jodl that our first priority was the Italian Front and the bomber war. He viewed the Russian victories on the Eastern Front with a certain equanimity and was resting his hopes on a new offensive in the New Year and on the new weapons which would then be at his disposal. Zeitzler did not believe a word of it but Jodl still cherished certain hopes for the success of the new weapons.

This excerpt from At Hitler's Side: the Memoirs of Hitler's Luftwaffe Adjutant appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.