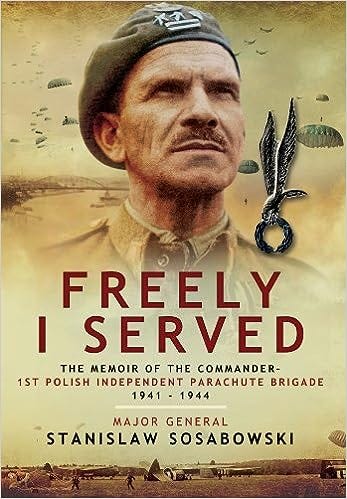

'Freely I Served'

An excerpt from the classic memoir by Stanislaw Sosabowski, commander of 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade

There are currently several re-issues of Arnhem-related memoirs in anticipation of the anniversary of Operation Market Garden in September 1944.

This week’s excerpt comes from the best overall account of the Polish involvement in the battle, Freely I Served: The Memoir of the Commander, 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade 1941 - 1944.

The following excerpt describes the paratroop drop into the battle area:

Conversation was entirely restricted to shouted comments about time and distance; none of us felt like talking. I am sure I speak for all of us when I say that our hearts beat violently when we thought of what was in store. Our breath came in shuddering gulps and our insides were a tight mass of anticipation.

Yet I managed to sleep and relax until imperceptibly the nose of the plane pointed downwards and pressure in the ears told us that we were gradually descending. A crew member came from the cabin and, pointing downwards, shouted "We are over Belgium and coming down to operational height."

The air rushing in the open doorway became warmer, bringing some life and feeling back into our frozen limbs.

The layer of cloud was much thinner over the continent and soon we were flying beneath them, in full view of the soldiers and civilians who gazed up in open-mouthed astonishment at the hundreds of roaring tightly-formationed planes.

We stared in awe at the fleeting pictures which came to us through the small windows.

"Look there," shouted someone near me. "Look at the burning buildings."

"D'you see that crashed plane over there?" another cried out. The roads and fields were pitted with deep bomb holes and scarred by artillery shells. The burnt-out hulks of lorries and tanks dotted streets and meadows. Here and there it was possible to see small groups waving wildly at us. At regular intervals there were smoking fires, forming a straight line, which we seemed to follow. I think it was a guide line into Arnhem, but the smoke spread a haze over the land, making it all seem unreal.

The American Jumpmaster came to the rear of the plane, taking up a position by the door, from where he could help us when the time came.

"Only twenty minutes to go," he shouted, pointing at his watch and holding up the fingers of both hands twice.

We all busied ourselves looking over the equipment, ensuring that all was in order. The Stick Commander came to give us a final check-over. We sat looking up at a point just above the door, where we knew a red and a green bulb would flash as a warning when it was time to jump.

"Five minutes to go," yelled the Jumpmaster.

Like one man, we lumbered to our feet and hooked our static lines to a cable running along the roof and locked them with securing pins. The plane started to weave about, and rise and fall, while we heard thuds like drum beats from outside. At first, none of us realised what it was and put it down to getting nearer the ground and hitting warm currents of air. It was not until I noticed several puff-balls of white smoke that I realised it was German flak. We were under fire! But it was all so remote and in a way unimportant compared with the battle we were about to face.

It was a difficult time for the pilots: the Dakotas were unarmed, with thin petrol tanks and no defence at all from shells. In addition, they had orders to keep strict formation and not to take any evasive action. Those young American pilots kept per- fect station in spite of the sight of flaming torches of hit planes plum- meting to earth.

The red light came on. "Action stations," screamed Dyrda.

We shuffled up the corrugated floor, bunching as close as possible. There were four long minutes still to go. An exploding anti-aircraft shell burst too near for comfort, bouncing the plane to one side. We lurched and recovered our balance.

The green bulb shone ghostlily above the door space and simulta- neously the Jumpmaster shouted: "GO!"

At the same moment the plane bucked as a crash under the belly indicated the first of the equipment containers had dropped from the bomb rack. The leading man pushed out a bundle of folding bicycles and in an instant flung himself into space. Number Two, Three, Four, and so on, each with a gentle push from the Jumpmaster.

Then it was my turn.

Following the man in front, I leaned forward, grasped both sides of the door and as the slipstream tried to push me back, I stepped with my left foot into nothingness. Hunching my shoulders and bending my legs, like an autumn ripe apple I fell. I was about to reap what I had sown in hard work and training. In a flash, I wondered: Had I planted well? Would I reap a good harvest?

I felt the tug of the parachute webbing on my shoulders I was floating down. All around me, as far as the eye could see, other paratroopers were descending. The man nearest to me let out the string of his kit bag until it dangled thirty foot below, countering the oscillation of his body.

Looking up, I saw with horror a Dakota, with flames pouring from both engines: yet I noticed too that the plane kept on a steady course and paratroopers still came in order out of the door. The rattle of machine guns grew louder as the thunder of the planes died away. Balls of cotton wool still appeared among the parachutes, but now they had a vicious crack of defiance.

I saw the green grass of Holland coming up to greet me, my feet touched and I sprawled sideways into the dampness of Europe. My right hand went automatically to the harness release box: I turned the metal disc, banging it smartly and the harness fell from my shoulders and groin. I rolled and the khaki canopy collapsed to the ground. Standing up, I unzipped my outer overalls and let them drop to my feet, while my eyes searched anxiously around.

Shells were whistling down and mortars bursting with their characteristic explosive crack. Machine guns were ranging the whole area. I saw unorganised groups of men getting themselves out of their harnesses and others unpacking containers; but, further away, I noticed orderly files of troops marching firmly towards rendezvous points. I picked out the group of trees where my Headquarters had been ordered to assemble. My landing had been near a canal and, if I had drifted only a few more yards, I would have had a very wet welcome to Holland.

Nearby, I saw one soldier with his head in the grass and his backside sticking in the air.-"Don't stay there," I shouted. "You'll get a very painful wound; get off to your rendezvous."

Directing other soldiers who looked enquiringly at me to the assembly point, I made my own way there.

On the slope of a moist dyke I came upon the body of one of the first of my soldiers to be killed. He lay on the grass, stretched out as if on a cross. A bullet or a piece of shrapnel had neatly sliced off the top of his head, but his face was in repose without regret or hate. I wondered how many more of my men I would see like this before the battle was over, and whether their sacrifice would be worthwhile?

At the Brigade rendezvous, I found my aide-de-camp and the thought went through my head that his wife's trust in my luck had been justified; she would be very thankful.

The Wireless Officer already had a transmitter working and was asking out-stations to report their strength and state of readiness to move. Smoke put down by our mortars was drifting across the fields, obscuring our movements from the enemy, who was raking the area with fire.

In some spots on the Dropping Zones my troops were having to fight their way into the cover and comparative safety of the woods.

This is an important work since the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade made a significant contribution to the battle and suffered heavy losses doing so - yet their reputation suffered in the post-battle blame game after the failure of ‘Market Garden’. It did not help that Stanislaw Sosabowski had made a number of criticisms of the plan in advance of the operation, criticisms that looked very prescient in the aftermath. ‘Freely I Served’ gives a very good exposition of the shifting priorities, plans and delays that the Poles were subjected to immediately before the battle.

Sosabowski had distinguished himself during the First World War - fighting the Russian Imperial Army - before being seriously wounded in 1915. He rose quickly in the Polish Army in the interwar years and his regiment were relatively successful in their part in the defence of Warsaw in 1939. He escaped captivity following the Polish collapse and then dedicated himself to building up a Polish force abroad, first in France and then in Britain.

This excerpt from Freely I Served: The Memoir of the Commander, 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade 1941 - 1944 appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.

Recently on World War II Today …

Midget submarines attack Tirpitz

The Royal Navy had sunk the Bismarck in 1941 but her sister ship, the Tirpitz, continued to threaten the sea lanes. The experience of dealing with the Bismarck had demonstrated that a large force of capital ships and aircraft had to be available if she put to sea. The mere existence of the Tirpitz hiding in the Norwegian fjords, meant that substantial forces were tied up, waiting to respond should she sortie out to attack the convoys to Russia. She had had a narrow escape when she

USAAF fighters surprise the Luftwaffe

In the bombing war against Germany, the early expectation that the USAAF Flying Fortresses would be sufficiently well-armed to defend themselves had proven to be misplaced. Furthermore, the Germans had been quick to re-organise their air defences to cope with attacks from the RAF at night and the USAAF by day.