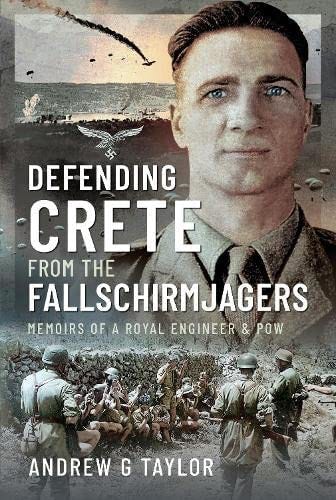

Defending Crete from the Fallschirmjagers

A new account of the contribution made by the Royal Engineers to the rear guard action, as the British withdrew from Crete in 1941

Eighty years after the war a steady trickle of memoirs continue to emerge. Many are appearing in translation for the first time but a rare few are completely new discoveries.

It was more dangerous to run away from a demolition because one might easily fall, twist an ankle or break a leg - and again it is always a point of honour for a sapper to walk away, not run.

One such discovery is the memoir of Royal Engineer Jack Seed (1920-2005). He completed his typewritten draft in the 1970s - and it had been quietly gathering dust until rescued by his grandson. Defending Crete from the Fallschirmjagers: Memoirs of a Royal Engineer & POW is being published for the first time by Pen and Sword later this month.

As well as being a valuable contribution to the history of the Royal Engineers and adding to our knowledge of the British Army’s experience on Crete in 1941, this also has much to say about the experiences of the ordinary soldier as a POW in Germany. There are many memoirs from officers who were POWs but the experience of the ordinary soldier is less well documented. Jack Seed paints a vivid picture of his experiences.

The following excerpt describes part of his time during the last days on Crete:

We were now allotted to small demolition parties, mine consisting of a lance sergeant, myself, a couple of drivers and six sappers. We had two vehicles, one a 15cwt open truck with the explosives and demolition stores, and a 30cwt truck with other stores such as picks and shovels, sledgehammers and crowbars, also more explosives and ammunition.

The lance sergeant with his driver and the sappers took the 30cwt truck in front and I and a driver followed with the 15cwt truck.

As per our training, we carried red flags displayed on our vehicles to denote explosives being carried, but we soon dispensed with them after nearly being shot up by German fighter planes. It was obvious they also knew what red flags on vehicles meant and there was no point in us advertising the fact any more. The demolition parties were given their locations and targets on the road of retreat and we set off in our vehicles at various intervals.

Our turn came and off we went. I couldn’t help feeling most uncomfortably exposed as I sat opposite the driver on the Mottley mounting seat, much higher than the normal seat and specially made to swivel around from side to side with a Bren gun mounted on the special fitting in front of me. We also had our rifles stuck in the racks at our side and a German sub-machine gun some of our boys had ‘won’ when returning to our lines during the first couple of days of the battle.

I also remember as we were going along the road, we came across some infantrymen marching towards us in single file on the sides of the road. We exchanged greetings and they told us they were Marine Infantry who had landed during the previous night from a destroyer and that men from the Middle East Commandos had also landed.

This gave us much heart and we saw no reason why more troops couldn’t be landed and we could still put a stop to the Germans, and the great ‘IF’: if we only had some fighter aircraft.

We were now travelling south, across the island, through torturous roads badly potholed, the terrain becoming more and more mountainous.

During a quiet spell on the road, a German observation plane, the ‘Storch’, started patrolling and nosing about up and down the canyons. We kept dead still until he was almost opposite us, then we let him have it with every weapon we possessed. He was a sitting duck and hadn’t seen us and I could see the shots from my Bren gun cutting into him from his nose to his tail.

Eventually, we arrived at our location for demolition; it was a huge culvert round a bend in the road. We unloaded some explosives and equipment and took the trucks a little further up the road into a cutting with rocky cliffs on each side, and also on the next bend. This would protect them from the air. At the demolition site, the cliffs rose straight and high up one side of the road, with a drop of hundreds of feet on the other side of the road.

There were vehicles crammed with men travelling through our new position to the point of evacuation at Sparkia on the southern coast. They all looked as fit as us and, were armed and we still wondered why these men were not being organised to fight. It looked to us as though everyone was running away.

There was one hell of a scatter when the German fighter planes came whizzing overhead; they couldn’t come down too low owing to the high mountainous cliffs around, but the mere sound of their guns put the fear of Christ up everybody. During a quiet spell on the road, a German observation plane, the ‘Storch’, started patrolling and nosing about up and down the canyons. We kept dead still until he was almost opposite us, then we let him have it with every weapon we possessed. He was a sitting duck and hadn’t seen us and I could see the shots from my Bren gun cutting into him from his nose to his tail.

Of course, he was soon out of range, disappearing round a bend, but we could hear others further along the road shooting away at him, then we heard an almighty crash and saw a plume of black smoke rising; at least one more German had bit the dust.

We had a mobile Bofors ack-ack gun parked very close to us for some time. He had probably been sent to give us protection from air attack, but he only made things worse. We had been getting on well with our demolition job before he came on the scene, and now the German fighters were buzzing around us like bees round a honey pot.

Very soon three stukas paid us a visit. They circled round whilst each made a separate diving attempt to bomb the Bofors gun, but again they couldn’t dive as low as they normally did, owing to the cliffs. They came far too close for our liking; I was still on the Bren gun popping away as fast as I could. We could clearly see the bombs leave the aircraft, narrowly missing the road to explode down in the chasm below us. They certainly gave us a nasty turn.

When they had gone, our sergeant went along to the Bofors gun crew and told them in plain English to get to hell out of it – and that’s putting it mildly. There were some heated words on both sides, but the gun packed up and pulled out, not towards the rear, we were pleased to see, but towards the ‘sharp end’.

Consequently, we were left alone after that and we got on with our job. Within a few hours we had our culvert all nice and ready for blowing and all we now had to do was wait for the order to ‘blow’. This was the worst time of any. We could tell when the ‘sharp end’ was moving to us. Our forward demolition teams would come through and give us the latest news whilst on their way to leapfrog us on to their next job. Again, we would hear the sounds of battle coming closer; one or two Bofors guns would come through accompanied by their crews and ammunition, 2-pounder anti- tank guns, etc.; the rearguard infantry would come and take up positions and lastly two ancient ‘I’ tanks (infantry tanks) would trundle up the road, covering each other with their fire at each bend in the road, and the last of the infantry with the tanks.

When everyone had passed by us we were usually told to ‘blow’ by our own OC, a dynamic little man who seemed to be tireless, and by which time, however, the Germans were sending over their 3-inch mortars at us.

Usually, the sergeant and I lit the fuses and after making sure they were properly burning we would leave the demolition as per the ‘book’ and walk steadily away to our awaiting trucks with their engines running.

It was a nerve-racking few minutes, thinking with every step we were going to walk into a bursting mortar or get shot in the back.

It was more dangerous to run away from a demolition because one might easily fall, twist an ankle or break a leg and again it is always a point of honour for a sapper to walk away, not run.

This then was the general pattern of things now, rearguard action after rearguard action all the way to Sparkia. We lost track of time, we had no food, we tried to live off the land, but many hundreds had been there before us and there wasn’t much left for us.

This excerpt from Defending Crete from the Fallschirmjagers: Memoirs of a Royal Engineer & POW appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.

Recently on World War II Today …

HMS Storm becomes a submarine

21st August 1943: A young officer takes his first command on her first dive

For a submarine commander there was no more demanding test than the first dive. Edward Young had been with HMS Storm, a brand new S class submarine since June, overseeing the final stages of construction and dealing one or two early mechanical difficulties. It had to be hoped that they had all been resolved. It was not unknown for submarines to develop catastrophic failures at this stage.

New Eastern Front realities

But being “encircled” was not quite the same as being taken “captive”. Some troop elements gained considerable practice over the course of time in being encircled and then breaking out or exfiltrating. But you never knew with certainty from one mousetrap to the next, whether there was once again going to be a hole large enough to escape through.