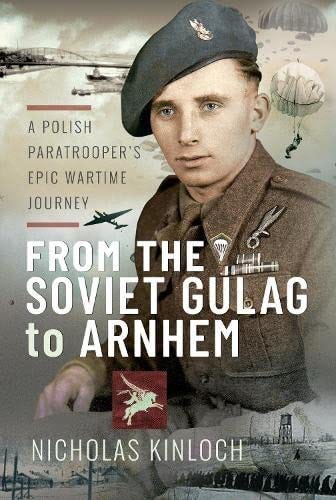

From the Soviet Gulag to Arnhem

The extraordinary story of Stanislaw Kulik's epic odyssey across the Soviet Union and on to Britain to become a Paratrooper

The German invasion of Poland in September 1939 saw millions of lives thrown into disarray. But it was the invasion of Poland by Soviet Russia in the middle of September 1939 that most affected the Kulik family from eastern Poland - “a typical Polish family in the 1930s, and that meant large and poor and Catholic”. In February 1940 they were woken in the night, given half an hour to gather their belongings - and deported to Siberia. Their small farm was seized by the Soviet state.

A desperate struggle for survival in exile began. Hope resurfaced after Hitler invaded Russia in 1941. The Poles were no longer potential enemies of the Soviet state. The formation of a Polish Army to fight the Germans was announced. But for seventeen-year-old Stanislaw and his brother that meant a journey of months, completely unsupported, foraging for food all the way, exact destination unknown.

Just published is From the Soviet Gulag to Arnhem: A Polish Paratrooper's Epic Wartime Journey.

Searching for the Polish Army would take Stanislaw across Russia - he became separated from his older brother - and then on through Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to Iraq:

I had been hungry ever since I arrived in bloody Siberia and it hadn’t got any better since I left. Jesus, that had been almost two years! Almost two years since we were taken from Poland! Two years of shit! Two years of hunger, illness and no energy and seeing people die. I could just about see all the bones in my body... I prayed to Jesus and Mary and God every day. Why have they done this to us? What did we do to deserve it?

And so, in desperation and hopelessness one day, the three of us killed, cooked and ate a dog, as we were so hungry. It was a dog that we saw on the street; I told myself it was a stray dog. A local man saw what we were doing. He started angrily shouting at us as he came over. ‘You bloody Poles, you killed a fucking dog! You’re like animals!’

‘You never give us any damn food!’ I shouted back. ‘If you fed us properly, then we wouldn’t have to!’

I cried after that; after eating the dog. What are we turning into... it’s true what he said, they’re turning us into animals... eating dogs... What next... I was losing hope that I would ever find Billy and the Polish army.

I need to find them soon, I thought to myself or I’m going to go crazy or die from hunger, or both. I’ve been travelling for months since Siberia. My mum and younger brother died there, for fuck’s sake! Then I had to leave behind my dad and sister and then I lost my older brother too, and for what? I’m 17 years old, with none of my family, starving and I’m eating fucking dogs. I can’t find my brother and I still don’t know where the Polish army is...

***

But then, just when I felt at my lowest ebb, and that all hope was gone, I heard that the Polish army was assembling nearby, beside a city called Kermine. It wasn’t a long journey on the train, only a few hours, but once I arrived at the station I was told by the police that I had to walk to reach the rendezvous point with the army.

The army camp was near the mountains, outside the town. I walked uphill in the direction that I had been shown, but it was getting cold and dark and I was tired. Snow started to fall and as I walked further uphill, it began to lie more thickly on the ground. I saw a big haystack, and wondered whether I could make a hole and sleep in there. I thought it might be more insulated and warmer inside. You could see animal marks round the haystack where they came to eat and sleep. No one seemed to be around, but when I started walking towards the haystack, someone suddenly appeared out of nowhere and tapped me on my shoulder.

‘Where are you going?’ he asked me. I explained that I was looking for the Polish army, but it was getting late so I was going to sleep in the haystack. The man shook his head and told me, ‘don’t sleep there, son; it’s too cold, you’ll never wake up... There’s a village about 2km ahead,’ he continued, pointing along the hillside. ‘There is an army camp there where you can spend the night; they have a canteen there too.’

I don’t know who that man was but maybe he saved my life. I carried on in the dark towards this village with the snow falling harder around me. There was a full moon rising over the hills, which helped to light the way and reflected off the snow. When I reached the village there was indeed a small army camp there and they gave me some bread, soup and Russian tea, as well as blankets to sleep on the floor. It wasn’t the main camp and wasn’t a place where I could join the army, but after months of searching it was the first sign that I was getting close to my goal.

For the first time I felt that maybe I would make it after all; maybe I would be able to find my brother again; maybe I would be able to join the Polish army and get some food and some clothes and shelter and then somehow be able to go back home. Despite my tiredness, I was so excited that I could hardly sleep that night. I was up early the next morning, my heart racing; could this be the day when I would finally join the Polish army?

I didn’t want to waste any more time. I got directions and set off as soon as the sun was up. My body was tingling with excitement and anticipation, but also anxiety and nerves; what if the Polish army camp wasn’t here after all or what if they didn’t want me? The adrenaline started pumping even harder when I saw an army camp come into view in the distance. As I got closer, I could see that the camp consisted of accommodation tents, as well as a kitchen and a store; square tents, maybe five metres on each side, with the roofs secured by ropes fixed into the ground.

The camp was close to the mountains with high peaks behind. When I arrived, I stopped at the edge of the camp, suddenly unsure what I should do or where I should go. There were soldiers moving about helping to set up more tents, and bustling about the camp. I could hear them speaking to each other, with the odd word coming across to me on the breeze; they were speaking in Polish. This must be it! This must be the Polish army camp! I just stood there and watched them for a few minutes, allowing myself for a moment to relax and realise that I had finally made it. I had found the Polish army.

Then, eventually, one of the soldiers saw me. He waved me over with a smile, and told me that he would take me to see the commanding officers in one of the tents. It felt so good to hear his Polish accent. The two officers were middle-aged and dressed smartly in uniforms with neatly trimmed moustaches. They looked me up and down; I was standing there in clothes which were like rags, falling off me as I was so skinny.

They asked me my name and how old I was. I told them, and then I told them that I wanted to join the army. The first officer looked at the other one, and shook his head. ‘We’ll never be able to get him into the army; he is too young!’ My heart suddenly sank as I stared in shock at this man with his smart moustache; could it really be that I had spent months travelling from Siberia, all around the Soviet Union, looking for the Polish army, and now they were not going to allow me to join because I was too young?! Were they going to send me away? Back to Siberia? I started to feel like I might even be sick; I couldn’t stand being sent away! I had seen just a glimmer of hope; a ray of light at the end of the tunnel and now it was all going to be taken away again? Just like that!

No! I couldn’t let that happen! I was about to start talking, to argue my case; I was not going to go without a fight – did they have any idea what I had been through, what I had seen? I had seen more by the age of 17 than some people had seen in their whole lives. Did they know what I had lost and risked to get here? That my mother and brother had died; that I had left my father and sister behind, and lost my older brother, all in the hope of finding the Polish army. And I had survived on my own, somehow surviving and making my way here. I know how to use a gun and live off the land from growing up in Poland and isn’t that exactly the kind of skills that you want in the army?

But now they are sitting there in their smart uniforms with me standing here starving in my rags, and they are saying that they don’t want me because I am too young! I was about to open my mouth and start saying all these things, when the first officer began talking again. ‘Look, this kid wants to join and we need soldiers. We could add a few years on to his age. Who would know? There is no birth certificate that could ever check it.’

So that’s just what they did. When I went to bed that night, I just lay there for a time, staring up at the roof of the tent. I was filled with contented, shocked, disbelieving happiness. I couldn’t believe that I had made it; part of me was worried that this was a ruse by the Soviets, that someone would come round at any moment and throw me out. But it was true, more than six months after leaving Siberia, after being lost and alone, hungry and hopeless, I had finally found the Polish army.

This excerpt from From the Soviet Gulag to Arnhem: A Polish Paratrooper's Epic Wartime Journey appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.

Recently on World War II Today

a