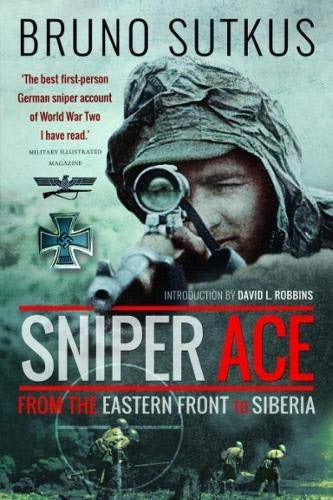

'Sniper Ace'

An excerpt from the extraordinary autobiography of Bruno Sutkus, describing life on the front line of a Grenadier regiment - even before he began work as an independent sniper

Bruno Sutkus was born in Eastern Prussia, close to the Lithuanian border, to Lithuanian parents in 1924. It was to prove to be a problematic background, as he was neither fully German nor fully Lithuanian. The Germans were not fussy about citizenship in 1943 - he became a naturalised German and was conscripted into the Wehrmacht. But by the time he returned to his family in Soviet-occupied Prussia in 1945 he was regarded as stateless - and conscripted into the Red Army.

Deserting from the Red Army he joined the Lithuanian resistance who were engaged in a war of independence against the Soviets. When eventually captured by the Soviets Sutkus’s past caught up with him. Not only had he served in the Wehrmacht but it was discovered that he had served as sniper - and a very successful one. Sutkus was banished to Siberia and endured many years of hard labour.

Sutkus would not return to Germany until 1990, and was not able to reclaim his German citizenship until 1997. He died in 2003. Sniper Ace: From the Eastern Front to Siberia was first published in English in 2009.

The following excerpt covers Sutkis’s experiences when he joined the Wehrmacht in the summer of 1943. Just two weeks into his training, he was recognised as an exceptional marksman - and sent off to sniper school:

At the end of July 1943 we boarded camouflaged railway goods wagons and headed by night to the field-training battalion in Russia for further training. This we received during the day, for at night we had to guard the Minsk-Orsha railway line, a favourite target for partisans.

Once I fell asleep on sentry duty. When I woke up my rifle was gone; the duty sergeant had confiscated it. I was handed over to the guard commander and locked in a cell. I felt ashamed. At midday I was escorted to the company office by the duty NCO and two privates wearing sidearms. Oberleutnant Braun explained how serious a matter it was to fall asleep on guard and the dangers that it could give lead to. He decided to let me off with a warning this time but I had to scrub the corridor as a punishment.

On the training company's first session with live rounds I excelled in the presence of Oberleutnant Braun and the battalion CO. At one hundred metres on the twelve-ring target I scored four twelves and an eleven. Next I had to fire five rounds at a camouflaged target and scored three twelves and two elevens. I did not stay long in the training company. After a month or so I was drafted to the Sniper School at Vilnius in Lithuania.

The school was located in a barracks near the St Peter and Paul Church. The same complex housed an officers' training establishment. Our course lasted from 1 August to the end of December 1943.

We were shown captured Russian film from which we gained an idea of the things a sniper had to master, especially fieldcraft, concealment, marksmanship (of course) and range estimation. Over these five months we learnt to absorb all the minute details a sniper had to bear in mind in order to spot the enemy hidden in the natural environment and to avoid being picked out himself.

The instructors were good. In the countryside they taught us how to recognise a target, pass information, estimate range and shoot at moving targets. I developed great accuracy in the latter. I realised that in those five months I had to absorb what I could in order to survive in the field. At the end of the course all those who qualified received the most modern sniper's rifle with telescopic sight, binoculars and a camouflage jacket. I was given a certificate confirming my passing out from sniper school and was warned never to allow another person to handle my rifle.

...

Dead Germans, Russians and Hungarians were strewn all around. The corpses had lain some time in the sun, and were bloated, black and decomposing. We relieved the Hungarians, who left their dead where they lay.

[Sutkus joined 68. Infantry Division in the spring of 1944]

We set out for the front, where we were to relieve a Hungarian unit that had been involved in heavy fighting and severely mauled in the western Ukraine. We reached the assembly point in the afternoon and camouflaged up to avoid being spotted prematurely by enemy air reconnaissance. We were in the Lemberg area, where 68. Infantry Division formed part of 1st Hungarian Army.

Finally it was the real thing, and I trembled at the sound of battle, the thunder of the heavy guns and the rattle of machine-gun fire. Once it grew dark we went forward, passing a burning Soviet tank that had got through our lines and been hit by a Panzerfaust. It stank of burning flesh. Dead Germans, Russians and Hungarians were strewn all around. The corpses had lain some time in the sun, and were bloated, black and decomposing. We relieved the Hungarians, who left their dead where they lay.

The enemy had noticed activity in our sector and shelled the trenches. Very close by was a farm where we set up a mortar in the centre of the courtyard. During a pause while the crew was taking refreshment a shell exploded amongst them, decapitating one and ripping another open from chest to abdomen. We had occupied the sector two hours and already had two men dead. It occurred to me that I should cover over the corpses with straw, but then I began to tremble and got away from the scene as quick as decently possible.

At 1000 hrs the artillery fire stopped and the Soviets attacked with tanks and infantry. This was a local probe, searching for the weak spots in our front line. Many of our men began to fire at a range of 500 to 600 metres, mostly from anxiety. One had to wait until the enemy came within 200 metres to expect any success. I had overcome my own fears much earlier. Naturally I reflected on dying and recalled my mother's parting words not to kill, but only to do my duty. This was all very well, but now we were soldiers and had no choice but to shoot. It was either them or me!

Their trenches had an 'Ivan' every ten to fifteen metres. We had fifty to seventy metres between each grenadier. Our casualties were not replaced, so our trenches became gradually less populated. Nevertheless the front line had to be held at all costs.

Amongst the Soviet infantry I saw an officer of Asian appearance driving his men forward towards our trenches with pistol drawn. I shot him down. I kept firing. Each round was a hit. The infantry was forced to seek some cover. Anyone who stood up and attempted to advance was hit. The commissars remained behind their soldiers, herding them forwards into our defensive fire. I aimed first at the commissars and shot them all down. When the leading ranks of infantry noticed that the commissars were out of it they turned and went back to their own lines The attack on our sector had been warded off.

Next the enemy tanks and infantry attacked our neighbouring company. We concentrated fire on the Russian infantry to separate them from the tanks, for the combination of infantry and these steel colossi was greatly feared. Before the attack I had an issue of 120 rounds. Now I had to request a fresh supply. My expenditure during the attack was not logged. While it was under way I noticed that many of our men had set their rifle sights for 600 metres initially and forgotten to adjust it to 100 metres as the enemy closed in.

At first my presence in the ranks as a sniper was hardly noticed. Only when it began to be realised what a sniper could achieve and how much depended upon him did the opinion of my comrades change.

The enemy had certainly noticed that a sniper was operating in the sector of the front directly opposite them, for now they moved about more cautiously. I could have taken out quite a few more of them but was anxious not to betray my position.

First I took a very good look at the terrain and estimated the distances. No Man's Land was about 500 metres wide. There was a Russian sniper ahead of their trenches and well camouflaged. He had a good view of our lines and had inflicted losses on our men.

Their trenches had an 'Ivan' every ten to fifteen metres. We had fifty to seventy metres between each grenadier. Our casualties were not replaced, so our trenches became gradually less populated. Nevertheless the front line had to be held at all costs.

This excerpt from Sniper Ace: From the Eastern Front to Siberia appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.

Thank you for reading World War II Today — your support allows me to keep doing this work.

If you enjoy World War II Today, it would mean the world to me if you invited friends to subscribe and read with us. If you refer friends, you will receive benefits that give you special access to World War II Today.

How to participate

1. Share World War II Today. When you use the referral link below, or the “Share” button on any post, you'll get credit for any new subscribers. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

2. Earn benefits. When more friends use your referral link to subscribe (free or paid), you’ll receive special benefits.

Get a 1 month comp for 3 referrals

Get a 3 month comp for 5 referrals

Get a 6 month comp for 15 referrals

To learn more, check out Substack’s FAQ.

Thank you for helping get the word out about World War II Today!

Recently on World War II Today

Horror of Hamburg spreads

The last bombing raid of Operation Gomorrah, the coordinated bombing of Hamburg, took place on the night of 2nd August. The bomber force hit a thunderstorm as it approached the target area, Pathfinder marking could not take place and the eventual bombing was widely dispersed. Yet a final attack was hardly needed after the series of attacks since 24th July and the

Medals of Honor on New Georgia

In the Solomon Islands, the US had launched their campaign to take the New Georgia group (Operation Toenails) a month earlier, on the 30th June. Determined, often suicidal, resistance from the Japanese had forced the US to bring in fresh Divisions before they could attempt to ...