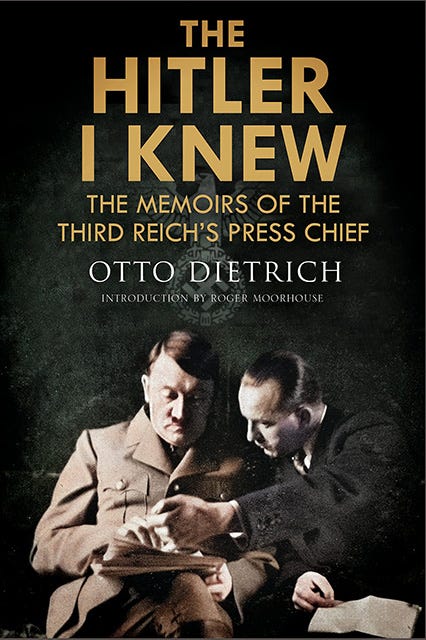

'The Hitler I Knew'

Otto Dietrich's reflections on Hitler written just after the war - from 'The Memoirs of the Third Reich's Press Chief'

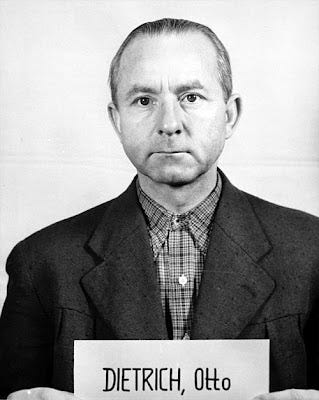

Otto Dietrich was Hitler’s press secretary and a Nazi insider - and member of the SS - from 1931 until March 1945. Although he had a much lower public profile, he vied for power with Josef Goebbels, the Propaganda Minister. He was not in Hitler’s inner circle but saw him frequently, enjoying his confidence almost right up to the end of the regime, when Hitler denounced him for ‘defeatism’.

Dietrich, a doctor of political science, had the opportunity to study Hitler over a number of years. Unlike many others - who became hopelessly devoted to Hitler - he managed to maintain some degree of objectivity. Immediately after the war he began to re-evaluate his belief in Nazism and became more critical of Hitler.

"only a thorough and uncompromising knowledge of Hitler's personality, of his innermost nature and his true character, can explain the inexplicable."

Dietrich was imprisoned for war crimes after the Nuremberg Trials in 1949 and wrote ‘The Hitler I Knew’ while in Landsberg Prison. This is a unique study, a genuinely critical reflection on Hitler’s abilities based on personal experience. His insights are based on observation and supported by many anecdotes about Hitler’s behaviour.

So The Hitler I Knew: Memoirs of the Third Reich s Press Chief (recently re-released in 2023) is an indispensable study for anyone interested in Hitler the man.

The following excerpt considers Hitler’s attitude to some of his contemporaries:

Hitler's opinion of the capabilities of various persons would vacillate wildly over the years. Windbags and incompetents he would hail as men of remarkable ability and heap them with honours. Years later, when these same people had shown what poor stuff they were made of, he would cry damnation upon them and discover that they were really just the opposite of what he'd earlier said.

And on the other hand, he would dismiss others, especially his opponents, as political charlatans, lily-livered rascals, and puffed-up nonentities. It would take years of grim experience to prove to him that they were nothing of the kind. When I think over the ideas he had about people, I can only say that the sure instinct which he so prided himself on failed him in nine cases out of ten.

A few words of explanation may be necessary. It is well known that Hitler's cult of personality, the great stress he laid upon individuals, was one of the most important branches of his philosophy. As a socialist Hitler made much of the idea of the "folk community." But for himself as an individual, there was something far more vital than the community-feeling: the individuality of the Herrenmensch, the man born to be a master.

Personality is rooted in individualism; community in sense of the group. To strike a balance between the two and join them in a creative unity was the great aim of Hitler's doctrine. But it also became the great problem of his life, and the one he failed to solve. In going into this matter, we touch upon ultimates, upon the underlying character of Hitler.

...

His egocentricity operated strikingly in his treatment of people around him. No one in the vicinity of Hitler stood a chance of developing into a personality in his own right. Passionate subjectivist that Hitler was, he had no understanding or sympathy for objectivity. Again and again, he stressed that he wanted to cleanse the minds of the German people of all "objectivity nonsense" and educate them to subjective thinking.

He was the purest subjectivist imaginable, for he evaluated people solely by the standard of their usefulness to his ends. That alone explains his disastrous misjudgments and the wild ups and downs of his favours.

Göring, who during the First World War had been a good fighter pilot, and who later was not a bad politician, was hailed by Hitler as the greatest genius in military aviation. Ten years later, when Göring could no longer deliver victories, Hitler decided that he was the greatest failure on record.

...

I always handed him the texts as well as the summary of Churchill's stirring wartime speeches. Hitler read them carefully, and I gathered from his entirely superficial and irrelevant remarks that he secretly admired them. But he would never discuss them in any serious way.

His grotesque verdicts upon his contemporaries and opponents in international affairs, verdicts which he would burst out with during ‘table-talk’, now have only historical interest.

He had Chamberlain labelled as the prototype of the hide-bound British conservative. He felt himself affronted because the British prime minister would not grant him hegemony on the continent and would not make a deal with him on a land-and-sea partnership between England and Germany. After Godesberg he was furious with Chamberlain, whose efforts to keep peace on the continent he denounced as betrayal and fraud. On the whole, however, he admired the British Tories and their skill at governing throughout the world. He never ceased to hope that British conservatism would eventually become his ally in Europe.

Churchill he hated as the greatest antagonist of his life, a man whose whole style of life was diametrically opposed to his own. Churchill's earlier life as a war correspondent, writer, and critic aroused antipathy and feelings of rivalry in Hitler, the orator, and he would rant against Churchill on this account.

Oddly though, he was enraged at the idea that Churchill sold his articles for large sums - although Hitler himself, when the "Movement" was in need, had accepted payments of several thousand dollars for his interviews with American journalists. Churchill, so fond of good living and good whisky, with his inevitable cigar in his mouth, was an offence in the eyes of Hitler, the anti-smoker and teetotaler. When he heard that Churchill was in the habit of dictating in the mornings from his bathroom, and when he saw a picture of Churchill bent over a prayer book, praying for victory, he became absolutely rabid.

I always handed him the texts as well as the summary of Churchill's stirring wartime speeches. Hitler read them carefully, and I gathered from his entirely superficial and irrelevant remarks that he secretly admired them. But he would never discuss them in any serious way.

Since the majority of his associates showed they were impressed by these speeches, Hitler himself preserved an icy silence on the subject. He would only pick away violently at random weak points in the speeches. He could not bring himself to admit that Churchill had the qualities of a great man.

Before the war, Churchill had once received a gauleiter of Hitler's in his London studio and had said, "Your Führer will be the greatest statesman in Europe if he preserves the peace of the world." Peace had not been preserved. In the war with Germany, the same Churchill who had hurled imprecations against Bolshevism formed an alliance with Stalin against Hitler. For this manoeuvre, Hitler so detested Churchill that objective judgment was out of the question.

Roosevelt was, to Hitler's mind, merely the capitalistic took of "international Judaism" Bolshevist Moscow being the other, the proletarian end of this conspiracy. To expose and defeat this double-barreled international plot was, he felt, the mission of his life.

With each presidential election in America, he hoped to see Roosevelt trounced. Sooner than provide Roosevelt with anything which would be useful to his cause, he forbade the German press and the German radio to attack Roosevelt during the election campaigns against Willkie and Dewey. Roosevelt's sudden death aroused in Hitler one of his last hopes, and to this he clung almost up to his own death.

With Stalin Hitler felt a certain sense of solidarity, although he appraised the Russian's personality differently depending on his own political direction of the moment. As the high priest of Marxism and the enemy of his own ideology, Stalin was someone to be hated. After the nonaggression pact, Hitler was full of praise for his ally. When Stalin became his deadly foe again, he did not stop respecting him, but he refused to say a good word for him.

This excerpt from The Hitler I Knew: Memoirs of the Third Reich s Press Chief appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.

Thank you for reading World War II Today — your support allows me to keep doing this work.

If you enjoy World War II Today, it would mean the world to me if you invited friends to subscribe and read with us. If you refer friends, you will receive benefits that give you special access to World War II Today.

How to participate

1. Share World War II Today. When you use the referral link below, or the “Share” button on any post, you'll get credit for any new subscribers. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

2. Earn benefits. When more friends use your referral link to subscribe (free or paid), you’ll receive special benefits.

Get a 1 month comp for 3 referrals

Get a 3 month comp for 5 referrals

Get a 6 month comp for 15 referrals

To learn more, check out Substack’s FAQ.

Thank you for helping get the word out about World War II Today!

Recent posts about Hitler:

18th July 1943: Dr Theodor Morell treats the Fuhrer for flatulence and constipation