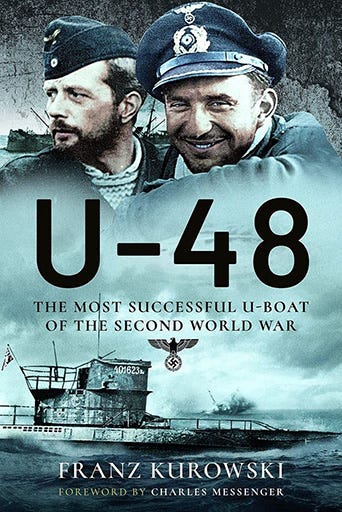

'U-48 - The Most Successful U-Boat of the Second World War'

This week's excerpt comes from an account of the U-boat war told through the history of one boat

Recently reprinted is U-48 - The Most Successful U-Boat of the Second World War, a popular title since its first publication in 2011. Through the story of U-48, which sank or damaged 57 ships in the first two years of the war, Franz Kurowski describes life onboard and the operations of a U-boat.

The commander of U-48, Kapitänleutnant Herbert Schultze, was a lucky man in many respects. His period of command coincided with the most successful period of U-Boat operations. His victories at sea brought him recognition and status; the Oak Leaves to his Knight's Cross was personally awarded by Hitler just as he finished operational patrolling in 1941. And he was lucky to survive these first two years - unlike so many of his peers - transferring to the training arm for the remainder of the war.

With many contemporary images of the crew and the U-Boat arm, this is a comprehensive picture of the service at this time.

The following excerpt is a reconstruction of U-48’s first sinking, on 5th September 1939. It illustrates how, in the early days of the war, some U-boat commanders were determined to operate within strict rules of engagement:

At 0815 on 5 September the bridge watch heard a dull noise to the south which sounded like a torpedo exploding. Shortly afterwards the radio operator announced the first reported sinking of the war by a U-boat: U-47 (Prien) had stopped and sunk a steamer at 45°29’N 9°45’W.

U-48 continued on a westerly heading. The fresh south-westerly breeze drove a long swell before it. The sky was covered occasionally by swiftly passing cloud masses, visibility remained mainly good.

‘Steamer 10° starboard ahead!’ the watch called out.

‘Man and load deck gun!’ Schultze responded.

The gun captain appeared on deck with the gunners. The first 88mm shells were passed up to the bridge and sent down to the gun through a chute. U-48 manoeuvred quickly into a favourable position. The commander sent by signal lamp: ‘Stop. Send a boat with captain and manifest.’

They were all blind on the steamer’s bridge. The ship steamed forward with nonchalant indifference.

‘Deck gun, one round across her bow!’

The 88 roared, a long muzzle flame flashed from the barrel and the shell splashed into the sea 50 metres ahead of the steamer, which now stopped. While the gun crew reloaded, a boat was lowered and rowed across to the U-boat. The ship’s master came aboard and handed Schultze his ship’s papers for examination. These left no doubt: a Swede with a cargo for Oslo. ‘In order,’ Schultze declared, ‘we must let him go. Gun crew unload and stand down.’

The shells on deck returned to the interior of the boat the same way they had come together with the empty shell casing. The Swedish captain was rowed back to his ship, and once aboard he dipped the Swedish flag in salute and proceeded with his voyage.

Late on the afternoon of 5 September mast-tops were sighted on the horizon. The commander was summoned to the bridge and shown the top of a superstructure. Schultze dived the boat at once to avoid being seen and reported. Trimmed at periscope depth U-48 headed at low revolutions towards her prey, the commander making occasional sweeps through the periscope.

‘The ship has no nationality markings,’ Schultze said as he crouched atthe attack periscope, seated in the saddle, circling the column with touches on the foot pedal. The crew were at battle stations. Apart from the commander’s commentary they were ‘blind’ and had to follow his orders precisely. When U-48 was sufficiently close to the merchant vessel he ordered: ‘Clear to surface! Bridge watch to tower. Gun crew ready to engage!’ After a brief pause he continued, ‘Radio room report at once if he transmits. Chief engineer – surface!’

In the tower Schultze peered over the battle-helmsman’s shoulder at the boat’s course. ‘Boat is through!’ Chief Engineer Zürn reported. Schultze unsealed the tower hatch and threw it open. Fresh air streamed into the boat. At the forward coaming of the tower he saw the bows of the steamer heading directly for U-48. ‘Bridge watch, come up!’ The lookouts came to the tower. ‘Gun crew, man bow gun!’

All went smoothly in the frequently practised routine of everyday U-boat life. Shells were brought up to the bridge and sent down the chute to the deck gun. The first was soon in the chamber. The gun captain measured the range to the ship. ‘Bow gun ready!’ Signal flags ordering the steamer to stop fluttered from the extended sky periscope. ‘Fire a round, just in case this captain is also blind,’ Schultze ordered.

Sea state was strength 3, and when the first two shells splashed into the sea ahead of the steamer, she put her rudder hard over and hoisted the Red Ensign. Seconds later the U-48 radio operator noted the distress call from the British ship: ‘SOS from Royal Sceptre, chased and shelled by German submarine, position 46o23’N 14o59’W.’

‘Steamer is transmitting and giving his position,’ Oberfunkmaat Wilhelm Kruse, the radio petty officer, advised. By doing so the steamer had put herself beyond the protection of international law. Her intention in transmitting was to call up enemy warships to her aid, a hostile act.

‘Fire at will at the steamer! Try to silence the radio room!’

Shells straddled the freighter in rapid succession. The gun crew slaved at the weapon, finally obtaining the first hits on Royal Sceptre. ‘Radio room silenced!’ the U-48 radioman reported.

Schultze saw the steamer’s lifeboats being lowered and ordered cease-fire in order to give the crew the change to abandon the burning ship. A few minutes later the radio operator of the stricken vessel began to send again: ‘From Royal Sceptre: chased and shelled by German submarine. Leaving ship position 46°23’N 14°59’W.’

There’s nothing else for it but a torpedo!’ Schultze said when he was given the fresh report. ‘Torpedo room, prepare single shot, tube 1!’

‘Tube 1 ready for surface torpedo,’ came the report from the bow room. ‘Tube 1, fire!’

The torpedo was expelled by a compressed-air cartridge and once free of the boat ran independently, straight and true over the few hundred metres to the target. The warhead of 350 kilos of TNT hit amidships. The control room petty officer noted the time: 1338 hrs. Royal Sceptre, 4,853 gross tons, sank very quickly. Within a few minutes she was gone. For the first time the radio operators heard through the hydrophones the eerie breaking sounds of a sinking ship. They would hear it over fifty times more aboard this U-boat.

The Royal Sceptre radio operator had remained on the ship to the end, calling for help for the crew in the boats, and he shared her grave. ‘Caps off, men!’ Herbert Schultze exclaimed emotionally, ‘Now you know who our enemy is. His name is defiance, if it’s for the flag. He will not spare us, because he is prepared to sacrifice himself in situations of the greatest danger.’

A few minutes after the ship sank, a lifeboat containing women and children was seen, and a second with crewmen heading towards France, over 400 nautical miles away. A short while later a lookout reported a second ship emerging from a squall. This was the British steamer Browning. When she had hauled up sufficiently close to read a flag signal flying from the periscope, Schultze hoisted: ‘Turn south – 13 nautical miles. Pick up crew of steamer Royal Sceptre.’

The Browning’s master could make no sense of the signal and gave the order to abandon ship even though he had not been fired upon.

‘We have to round up the lifeboats and escort them back to the steamer so that she can pick up the women and children of Royal Sceptre’, Schultze explained. ‘But do we really want to let that fat tub escape, Herr Kaleunt?’ the watchkeeping officer asked.

‘We are pursuing commerce warfare in accordance with the Prize Rules. Just imagine the fuss Tommy will make if we do not adhere to them strictly. The British have each one of our submarines under a microscope and will use the most minor error to make propaganda claims of atrocities which stink to high heaven. Therefore we must run a “get-you-home” service for these people.’

U-48 headed at full speed for the Browning lifeboats which were being rowed at a furious speed. As the submarine approached them, the master waved with both arms while the crew raised their arms in a gesture of surrender. Schultze stopped the boat where the lifeboats could easily drift up to it. ‘Listen, captain,’ Schultze raged at the man, who was now standing up in the nearest boat, ‘over there we have just left the crew of a ship we sank. You now row back to your ship, get aboard her, head for the lifeboats and save the shipwrecked people.’

This excerpt from U-48 - The Most Successful U-Boat of the Second World War appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.