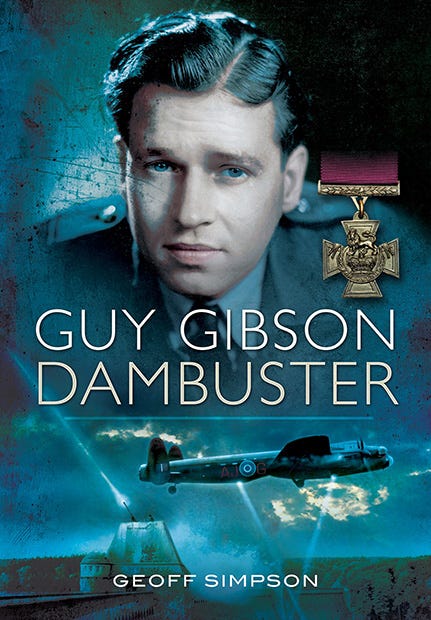

'Guy Gibson: Dambuster'

From the biography of the Dambuster's hero, this excerpt considers the circumstances of his final flight

Recently re-released is Geoff Simpson’s biography of ‘Guy Gibson: Dambuster’. Gibson had established a reputation for himself long before the Chastise operation as an able and fearless flyer, and had already been awarded the DSO. The award of the Victoria Cross after the raid, and a bar to the DSO, made him the most highly decorated RAF officer at the time. He was still only 24.

Gibson was soon much in demand for publicity in support of the war effort. He made a very successful tour of America and Canada in 1943. As a national hero the RAF wanted to keep him off operations, so for the first half of 1944 he was encouraged to write an autobiography. Enemy Coast Ahead was published to much acclaim in 1946 and has been in print ever since.

As well as tracking his career this biography considers the wider context of Gibson’s legacy, including the subsequent film and the building of a national legend. It does not shy away from some of the controversies surrounding the man who was known as the ‘bumptious bastard’ by some of his ground crew but very highly regarded by Arthur Harris, commanding RAF Bomber Command.

The following excerpt considers the circumstances of Gibson’s death in September 1944:

The Final Flight

There was much discussion and changing of plans at Bomber Command before the attacks for the night of 19/20 September were finalised. There was much to consider. The AOC-in-C wished to keep up the destruction of German cities.

SHAEF still required attacks on targets of tactical value, the destruction of which would assist the Allied advance across Europe. Operation Market Garden was deeply in trouble and needed help. The delayed third airlift of troops to join the fighting at Arnhem and Nijmegen was taking place. The weather over Europe threatened to cause problems. Fog might well descend over eastern England as the bombers were returning.

Bremen was selected as a target for No 5 Group and then this was changed to the twin towns of Rheydt and Monchengladbach, just inside Germany. There would be red, green and yellow areas of attack. Red was the key target, the centre of Rheydt, and required to be controlled by a pilot experienced in the latest techniques. Plenty of such men were available. None of them was chosen. Instead, to the astonishment of many involved that night, the controller would be Gibson. Some participants were also disconcerted by the decision to have three marking points.

Three pilots from No 627 Squadron, operating Mosquitos, would be marker leaders. The highly experienced Squadron Leader Ronald Churcher would mark on red and would be Gibson’s deputy controller.

Coningsby normally provided Mosquitos for No 5 Group controllers, but none proved to be serviceable. Late in the proceedings, No 627 Squadron at Woodhall Spa was asked to make an aircraft available and was told that the controller would collect it. There was also a change of personnel. The navigator originally allocated to accompany Gibson reported sick and Squadron Leader Jim Warwick, the Coningsby station navigation officer took his place. One account has Gibson walking into the mess and brusquely telling Warwick that his services were required.

Gibson and Warwick received a briefing from Squadron Leader Charles Owen who had been the controller on a previous attack on the area to be targeted that night. Gibson made it clear to Owen that he intended to select his own route home, ignoring the official instructions. Later, at Woodhall Spa, the atmosphere became charged as Gibson rejected the aircraft selected for him, giving no clear reason, and forced another crew to give up their Mosquito and take over the rejected aircraft. A few minutes before eight in the evening, Gibson and Warwick took off on what would prove to be their last flight.

Later returning crews would have different views of the success or otherwise of the organisation of the attack, perhaps a likely situation given the dispersed marking points. Red was a particular concern, with one of the issues being a problem with Churcher’s aircraft. Eventually Gibson decided to mark himself, but found that his target indicators (TIs) did not release.

The delay increased the chance of collisions and the Luftwaffe night fighters were arriving and beginning to inflict casualties. Some aircraft assigned to red began to bomb on green. Gibson then accepted that situation and issued an order to bomb on the green markers.

Churcher, overcoming his problems, finally managed to place red TIs accurately and bombs began to fall on Rheydt.

Crews heard Gibson telling them to go home and it is believed that he remained over the target for some minutes, assessing results. That would be normal for a controller.

Around half an hour later, about 2230 hours, residents of the Dutch town of Steenbergen saw and heard an aircraft. Some felt it was in trouble. It was seen to circle in the area of the town. Two crew members were visible. There were flames and the aircraft crashed.

Guy Gibson and Jim Warwick died in that crash. They were buried side by side in Steenbergen.

In March 1945 the St Edward’s School Chronicle carried the latest long list of old boys lost on active service. The names were in alphabetical order and first was Lieutenant (though the Commonwealth War Graves Commission gives him the rank of captain) Peter Robert Taylor Daniel, 4th Battalion The Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment) who had died in 1943 and would be remembered on the Athens Memorial. Guy Gibson came next and his death in action was described as an ‘irreplaceable loss’.

There followed the words penned by Warden Kendall which had appeared in The Times. ‘Others have spoken and will speak for many years to come of Guy Gibson’s gift of leadership; I should like to add a more personal word as to his character. He was one of the most thorough and determined boys I have ever known, both at school and afterwards, and nothing could move him from his purpose of flying, neither his original rejection when at school by the RAF, owing to his short legs, nor the offer of ground jobs, nor a seat in Parliament during the war. His letter in answer to a line of congratulations after his dam bursting exploits ended: “PS – was awarded the VC yesterday.”

He came back quite unspoilt from a tour in America, and got back to flying as soon as possible afterwards. Once, when officially resting ... he had to make a dangerous forced landing; a doctor drove up to help, and, finding him unhurt, took him back to the aerodrome. In the car he glanced at Guy and said: “It’s a shame they make you fellows fly so young.” Gibson appreciated the kind thought and the joke, but never said who he was.

‘He shared to the full all the strength and the virility and modesty of English boys of all ranks, with their amazing good humour in trying conditions; he would not have wanted to claim more than this.

One incident is worth recording. He was visiting his school after he had become famous and arrived just before dinner. The boys naturally asked him to speak, hoping to hear something of his action, so he was left alone with them. “What – am I to speak? Well, when I was a boy here Old Boys used to come down and say they never did any work. Don’t believe them. I worked like hell!” That and a cheerful smile was all they got from him, but they understood.’

Trish Knight-Webb vividly recalled Guy’s death. ‘I do remember the telegram arriving bearing the news and the terrible silence in the house. In those days things like death were not discussed with children of my age (around eight) so what I picked up was mainly atmosphere.’

Guy Gibson’s early and needless death added to the allure of his legend. It ensured that he will be remembered for his heroic and brilliant achievement over Germany in 1943, the memory undiluted by any later achievements or failure in a life of normal span. He was spared the frequent post war debate about the extent to which Operation Chastise had damaged the enemy war effort. That debate continues, though there should be none about the gallantry of the Dam Busters and the enormous impact they had on British morale and prestige.

Fatal Theories

Guy Gibson could have remained off operations, but died because he could not stay away from them. There are plenty of others who have had this compulsion for action in similar circumstances.

The story is well known of Douglas ‘Tin Legs’ Bader, newly released from Colditz, shocking an American officer by asking him where the nearest Spitfires were, so that Bader could have a final crack at the enemy.

...

The compulsion that led Guy Gibson to his death is well-established. However, the debate – and the research – goes on as to the circumstances of his death and it is highly likely that more evidence and revised ideas will emerge.

The author goes on to consider some of the theories surrounding Gibson’s final accident, including the suggestions that he was the victim of sabotage, of friendly fire (by an aircraft that misidentified his Mosquito as a German nightfighter) or as a consequence of unfamiliarity with the particular, Canadian, model of Mosquito that he was flying.

This excerpt from Guy Gibson: Dambuster appears by kind permission of Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Copyright remains with the author.